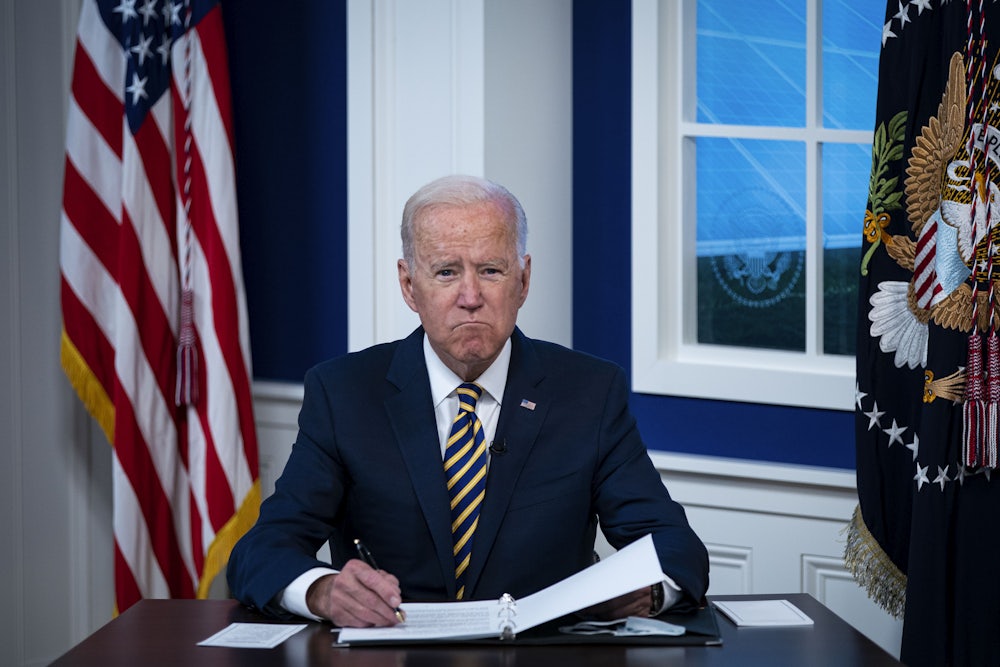

When Joe Biden entered the White House earlier this year, he arrived with the rising sense that the United States would at last realize the threats that illicit finance and trans-national corruption—kleptocracy, in other words—pose to both national security and domestic democracy alike. After all, the U.S. had just lived through four years of Donald Trump’s misrule, which provided a front-row seat to the spectacle created by a president drenched in anonymous wealth and bent on tilting American policy and subverting American democracy. Oligarchs and autocratic regimes alike exploited the opportunities that Trump’s corruption provided, launching efforts of so-called “strategic corruption” throughout his reign, knowing the White House would look the other way—if not offer a welcoming embrace.

Biden also swept to power amid a set of unprecedented policy moves geared toward finally begin patching up all of the U.S.’s numerous holes in its anti-money laundering regime. Just a few weeks before Biden’s inauguration, Congress passed legislation to finally ban the formation of anonymous shell companies in the U.S., the bedrock of the country’s years-long transformation into a haven for dirty money from around the world.

Biden didn’t take long to capitalize on that momentum. In just the first few months of his presidency, he took significant steps to make his own mark on the broader fight against kleptocracy. In June, the president formally elevated corruption as a “core national security interest,” placing it along the likes of terrorism and nuclear warfare for the first time. The White House also swiftly sanctioned Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, the man allegedly responsible for one of the greatest laundering schemes either country had ever seen—and who helped decimate local communities across the Midwest and Rust Belt in the process.

And yet, toward the end of Biden’s first year in office, signs of frustration in the anti-corruption community had become impossible to miss. Naturally, the White House has been juggling a number of complicated and era-defining issues, from a roiling pandemic to the efforts of Trumpists to continue the work of gutting American democracy. But as fall turned to winter, anti-corruption advocates still waited for Biden to become, as Ben Judah described his promise, “the anti-kleptocracy president.”

It’s not hard to see why they’d grown impatient. To take but one example, the White House waited until the end of the year before advancing some regulatory measures in the U.S.’s most popular destination for kleptocratic wealth: real estate. It’s a hopeful sign that more such reforms are on the way. It’s not a moment too soon: Thanks to a decades-long exemption from basic anti-money laundering checks, American real estate has ballooned into a go-to destination for anyone looking to launder any amount of dirty money. (A fantastically opaque tool to help bankroll, say, a luxury real estate developer into the White House, without anyone knowing about it.)

Under Obama, the U.S. launched so-called “Geographic Targeting Orders,” revealing the identities of those behind most residential property purchases in a select number of American cities. Despite the clear success of the program, the Biden administration spent much of its first year simply holding those requirements in place—leaving real estate in major American cities like Houston, Phoenix, Philadelphia, and Austin wide open to oligarchs and kleptocrats around the world.

Meanwhile, private equity firms and hedge funds are increasingly posing tremendous challenges to anti-kleptocratic efforts. Research shows that these private investment vehicles have blossomed into their own centers of money laundering, as fund managers can still work with whichever clients they’d like, perfectly freely, without even basic anti-money laundering checks. Despite the industry holding nearly $11 trillion in assets, the Treasury Department has spent years exempting fund managers from the kinds of anti-money laundering requirements that, say, bog-standard American bankers must implement. Small wonder that everyone from Russian oligarchs to Mexican cartel heads have begun turning to these funds for their financial secrecy needs.

In many ways, that creeping disappointment has been perfectly understandable. For much of 2021, an entire range of counter-kleptocracy tools remained untouched and unused. Kleptocratic networks around the world continued operating and continued turning to the U.S. for their laundering needs. And American industries—including everything from the art market and luxury goods providers to, as seen most recently in the Pandora Papers, the American legal sector—remain wide open for anyone looking for laundering services.

Thankfully, Biden and his administration can end this status quo with just a bit of executive creativity, a bit of legislative muscle, and a bit more willingness to open his administration to those ringing the alarm bells about the threats of modern kleptocracy. And as 2022 beckons, the administration shows signs of finally coming to life—and finally fulfilling the promises it entered office with.

Just this month, the administration released its 38-page strategy document laying out how the U.S. will fight corruption and kleptocracy. The document is, in many ways, a watershed, not just in the U.S. but internationally. In addition to the laundry list of policy pushes—transparency in real estate and private equity, new regulations on lawyers and trust providers, and plenty more—the document recognized the clear reality that the U.S. is a “significant destination for the laundered proceeds of illicit activity, including corruption.”

Moreover, the policy document specifically identifies American lawyers, accountants, trust providers, and other American enablers as key nodes in trans-national money laundering networks. As the document detailed, these American professionals “are often sought by criminal organizations to facilitate their illicit activities.” The language was as pointed as anything an American administration has used, and came alongside further announcements about increasing transparency for things like shell companies and real estate.

Shortly thereafter, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen voiced a truism previous administrations had long ignored. As she said, “there’s a good argument that, right now, the best place to hide and launder ill-gotten gains is actually the United States.” While the news was jarring to some, it reflected a reality years in the making. And it also signaled that the Treasury Department, arguably the most important federal agency in the fight against kleptocracy, is fully on board with Biden’s mandate. These new strategies and statements are an unprecedented shift in how the U.S. views the threat of global corruption—and the role the U.S. has played in fostering illicit finance around the world.

But the clock is ticking. In many ways, 2022 will illustrate whether the administration is serious about this fight against kleptocracy, and can actually translate this new rhetorical burst into reality. It’s said many of the right things thus far, and the new strategy documented is a clear sign of renewed (and welcome) momentum. But the anti-corruption community has high hopes—and is anxious for the administration to finally begin implementing the policies long overdue.