If you’ve read any national news stories over the past few months about the political implications of pandemic-induced school closures, you’ve likely come across Brian Stryker’s name. He’s become the go-to source for reporters and commentators—particularly those at The New York Times. The paper ran a Q&A with him in early December titled, “A Pollster’s Warning to Democrats: ‘We Have a Problem.’” His work has been cited in subsequent op-eds of The New York Times and was featured prominently in a recent Times piece built around the idea that more omicron-induced school closures urged by teachers’ unions could spell disaster for Democrats next fall. On the basis of a survey Stryker’s firm conducted of 500 Virginia voters, the Times stated unequivocally that “polling showed that school disruptions were an important issue for swing voters who broke Republican—particularly suburban white women.”

Stryker, a partner at the Democratic polling firm Anzalone Liszt Grove Research (which announced it’d be changing its name to Impact Research last week), gained this prominence following a widely circulated memo he and his colleague Oren Savir published in mid-November, which analyzed Republican Glenn Youngkin’s victory in Virginia’s gubernatorial election. The memo reported findings from an online focus group of 18 suburban Biden voters in Northern Virginia and the Richmond metro area, and states that while concerns over “critical race theory” were a problem for voters, school closures were a bigger factor. Perhaps most ominously, their memo quoted a Biden voter who cast her ballot for Youngkin as saying her vote “was against the party that closed the schools for so long last year.”

Democrats have plenty of reasons to fret about the upcoming midterm elections. While Joe Biden won by over seven million votes nationally in 2020, Democrats were devastated down the ballot. The party failed to flip any of the dozen state legislative chambers it had targeted and lost 13 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Election analysts attribute Biden’s victory in large part to suburban women who loathed Donald Trump, but Trump won’t be on the ballot in November, plus midterms have historically been bad for the party of first-term presidents. Voters are concerned about inflation, and Joe Biden’s approval rating hovers, roughly, at a troublingly low 40 percent.

Yet one much weaker midterm theory, curiously, has gained traction

among the political elite, especially following the rise of the omicron

variant. The slow pace of school reopenings in the 2020–21 school year, we’re

told, still represents a significant political liability for Democrats, one

that could grow even worse as some school districts close temporarily this

month due to Covid-19. Blaming teachers’ unions and Democrats who ally with

those unions is also part

of this cautionary tale. Alexander Nazaryan, a Yahoo News reporter, went so

far as to call Chicago’s teacher strike this month a “Reagan vs. air traffic

controllers moment.” If Biden doesn’t “stand up to” teachers’ unions on school

closures, Nazaryan warned,

“he loses credibility at a critical time in his presidency.”

Perhaps because many of the people who lead these conversations are frustrated parents themselves, the idea that school closures will come to haunt Democrats is something that to many of them feels true or, at the very least, highly plausible. Life remains logistically and emotionally challenging for parents in countless ways, especially those with kids under 5, and so there’s a sense that surely something’s got to give.

Throughout the first six months of the pandemic, many of those same voices also warned that Democrats would pay a steep political cost. That didn’t bear out in the 2020 election. The loudest critics have insisted that Democrats will push for a full return to remote learning—despite the truth that most politicians and union leaders have suggested only temporary accommodations as the country weathers the quickly rising and quickly falling omicron wave of infections.

Instead of a practical debate, online discourse creates an artificial dichotomy, in which one can only belong to one of two camps: an adherence to complete lockdown until we achieve “Covid-zero” or a complete return to pre-pandemic normalcy. But outside Twitter and op-ed pages, many surveys and studies have shown that actual parents and voters hold much more nuanced views. They can hate the harms of distance learning while determining when the pandemic has altered how they want to live and school their children. They can express frustration with their circumstances but maintain that not all problems have immediate resolutions and clear villains.

The latest eruption of the school-closure debate has been defined by a bout of amnesia, one that has erased the bountiful evidence of public sentiment from the 2020–21 school year.

Throughout the pandemic, including during the first few months of

2021, poll after poll showed that most parents and most voters—including the majority of Democrats and independents—were not in favor of sending kids back

to K-12 schools full-time, at least until teachers and seniors were vaccinated.

In mid-February last year, 74 percent of Democrats and 54 percent of

independents told Politico/Morning

Consult that states should wait to reopen until teachers had received the

coronavirus vaccine. A separate Quinnipiac poll from

the same time period found just 27 percent of adults thought schools were

reopening too slowly, with 47 percent of adults saying they felt reopenings

were taking place at the right pace, and 18 percent reporting schools were reopening too

quickly. Another February 2021 poll from

YouGov/HuffPost found just 27 percent of adults thought schools should be

completely reopened, with 29 percent backing partial reopening and 30 percent

supporting virtual learning.

The findings were consistent when pollsters talked to just K-12 parents. The University of Southern California asked a nationally representative sample of parents in late January 2021 how their child was learning—in person, remotely, or hybrid—and then asked what they would want for their child if they could choose any option. USC found that 75 percent of parents said their child was receiving the type of instruction they wanted. A separate poll, released by the National Parents Union, found that in mid-January, about two-thirds of public school parents were getting the kind of schooling they preferred for their kids, with about 20 percent wanting more in-person instruction and 10 percent wanting less. EdChoice, a national school choice group, polled U.S. parents monthly, beginning in May 2020, about their comfort level sending their child back to school. Parental comfort levels didn’t break 60 percent until April 2021.

This was all true despite millions of parents and voters expressing deep dissatisfaction with virtual learning, concerned about its toll on academic progress and children’s emotional and social well-being. Seventy-two percent of voters told RMG Research last February that they saw in-person learning as better than virtual instruction, and 57 percent of parents told Yahoo!/YouGov last January they thought their child had fallen behind academically. Sixty-four percent of parents whose children were learning remotely in October 2020 told Pew they were concerned about their child maintaining friendships and social connections, compared to just 49 percent of parents whose kids were attending school in person.

But it doesn’t require any great intellectual leap to bridge these two divides. One could easily favor in-person learning in the abstract, hold real worries about the implications of virtual school, and yet still determine that remote learning is the right call at that time given the risks of the pandemic. Individual families inevitably have different risk thresholds based on resources and other factors. Low-income, Black, and Latino families were more likely last year to prefer remote learning even as studies showed those children suffered greater learning losses in subjects like math and reading from virtual school compared to their white peers.

David Houston, an education policy professor at George Mason University and the survey director for the annual EdNext survey, told me that was indeed consistent with public opinion research. “We asked parents in spring 2020, fall 2020, and spring 2021, ‘Do you think your kid is learning more or less or about the same?’ Folks aren’t fools, they certainly don’t think their kids were doing as well as they would have under normal conditions,” he said. “But simultaneously we asked a question about satisfaction with the instruction and activities provided by their child’s school, and the rates were really pretty darn high.”

When kids returned from summer break in the fall of 2021, life looked quite different in most parts of the country. Things were far from the “normal” of what classrooms of 2019 looked like—delta was circulating, kids were often wearing masks, and individual classes would shut down for a period after a string of positive tests—but the vast majority of children were back learning in school buildings full-time.

Parental attitudes also lifted. Reputable polling has shown broad satisfaction among parents with having their kids back inside schools and no increase in negative views toward teachers’ unions. Surveys have also shown that voters—particularly Democrats and independents—are not holding Democrats responsible for last year’s school closures.

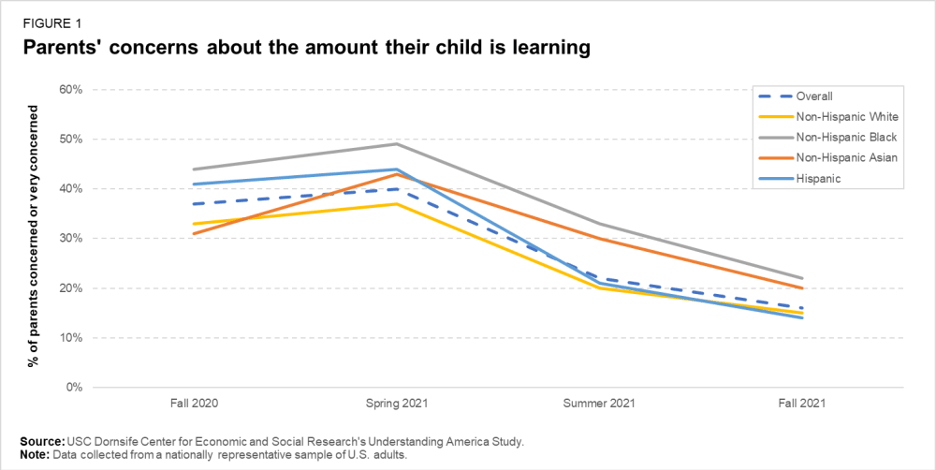

The University of Southern California’s Understanding America Survey surveyed parents four times during the pandemic: October 2020, when 29 percent had fully in-person school; April-May 2021, when 50 percent were in person; June 2021, when 79 percent were on summer break; and October 2021, when 93 percent were in person. The researchers found that parents’ concerns about their child’s learning had gone down significantly last fall. When asked about their school’s efforts to meet their children’s needs—including academically, socially, and mentally—82 percent to 91 percent of parents were satisfied in each area. “This level of positivity was consistent across subgroups,” they reported, “including by race/ethnicity, household income, parental education level, region of the country, urbanicity, partisanship, and grade levels.”

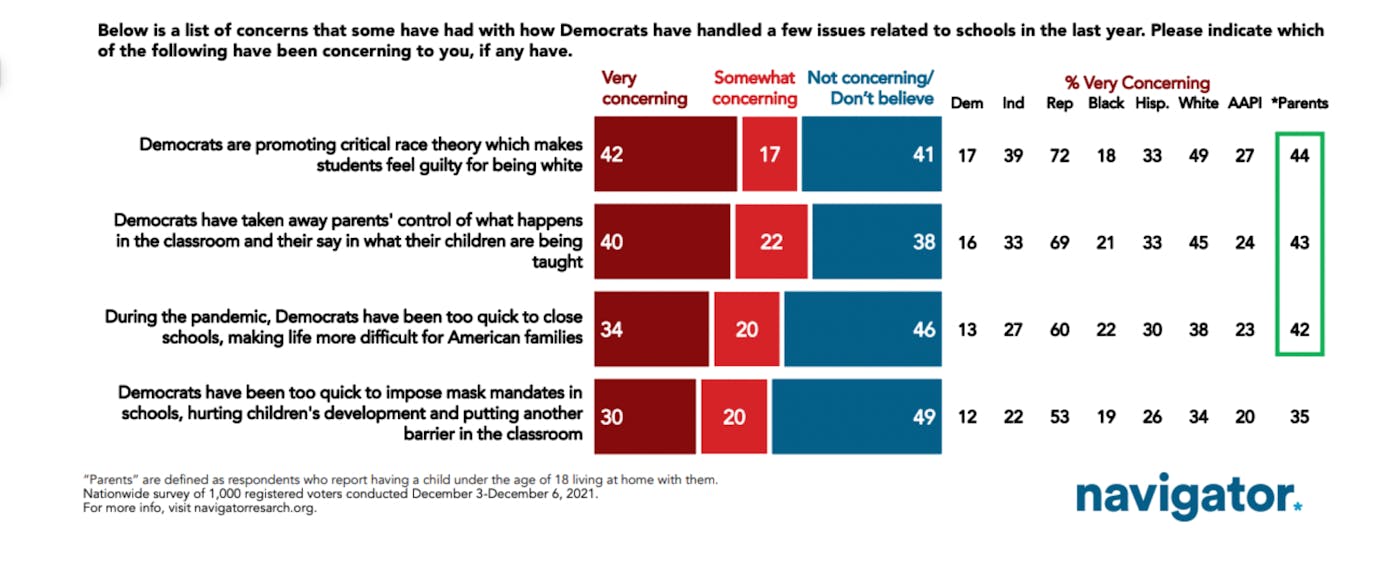

Likewise, in a nationwide

poll conducted in early December by Global Strategy Group and GBAO,

researchers found just 13 percent of Democrats and 27 percent of independents

described Democrats closing schools as a “very concerning” school-related issue

to them, compared to 60 percent of Republicans. More Democrats and

independents—17 and 39 percent, respectively—said they were very concerned that

Democrats were promoting critical race theory in schools.

In a national survey of public school parents registered

to vote conducted last month by Hart Research Associates and Lake Research

Partners, pollsters found 78 percent of parents expressed satisfaction with

their school’s overall handling of the pandemic, and 83 percent reported

satisfaction with their school’s efforts to keep students and staff safe.

Moreover, just 22 percent of parents said they felt their school waited too

long to resume in-person instruction, while three-fourths felt their school

struck a good balance between safety and learning (48 percent) or actually

moved too quickly to reopen (26 percent).

Although repeated efforts to pit parents against teachers were never successful, the national conversation shifted back to the artificial construct once journalists and talking heads began analyzing how Republicans retook Virginia’s governorship and gave New Jersey’s Democratic Governor Phil Murphy a much more competitive reelection than anyone anticipated.

The ALG survey and focus group provide useful insights. Focus

groups, like the best journalism, can be particularly valuable for drawing out

further hypotheses to test. But treating that research as dispositive is a

mistake, particularly when other high-quality surveys have found evidence that

conflicts with or complicates ALG’s findings.

Geoff Garin, a longtime Democratic pollster and president of Hart Research

Associates, did some polling for Terry McAuliffe during the election, followed

by an in-depth postelection survey of more than 2,400 Virginia voters after

the election on behalf of the Democratic Governors Association. “It’s very

clear that education was a dominant factor in driving the outcome of the race,

but there’s really no evidence that the question of school closures was an

important part of that,” he told me. Garin’s research found that 9 percent of

Biden voters switched to Glenn Youngkin in 2021 and that education was indeed a

top-cited issue for this pivotal subset.

But rather than school closures, Garin said, these people talked exclusively

about Terry McAuliffe’s comments surrounding parent involvement in school. In a

late-September gubernatorial debate, McAuliffe declared, “I’m not going to let

parents come into schools and actually take books out and make their own

decisions,” adding, “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they

should teach.” Youngkin’s campaign made those deeply unpopular remarks a centerpiece

of his campaign in the closing weeks of the race, running ads and

circulating petitions and fliers stressing that “Parents Matter.” Under the

umbrella of parental involvement, Youngkin’s campaign also leaned on other

issues agitating parents like mask and vaccine mandates, transgender rights,

and racial equity initiatives.

In the ALG memo, Stryker and Savir argue that, yes, McAuliffe’s gaffe resonated, but it really hit home because it played into existing frustrations parents had over school closures and feeling “that Democrats didn’t listen to parents when they kept the schools closed past any point of reason.”

Garin says his research showed no such thing. “It was completely clear in the surveys from the last few weeks of the election and postelection that voters were reacting to McAuliffe’s comments,” Garin told me. “Youngkin put that quotation front and center with an enormous amount of advertising; he and his campaign never related it to school closures.” Among the Biden-Youngkin voters, Garin’s research found 54 percent said McAuliffe’s position on the role of parents in schools influenced their vote, and 41 percent said his position on the teaching of critical race theory influenced their vote.

These aren’t entirely separate matters. As opposition to CRT becomes heavily associated with Republicans, liberals and moderates who also feel racial and social justice causes have “gone too far” are more likely to glom onto another slogan that allows them to express the same idea without feeling it’s so conservative. Christopher Rufo, the Manhattan Institute activist who got Trump to take notice of CRT in the fall of 2020, has embraced calling their legislative crusade against diversity, equity, and inclusion a “parent’s movement” and describes their efforts as a push for “parental transparency” on curriculum.

Mario Brossard, a senior research vice president at the Democratic polling firm Global Strategy Group, who conducted polling in October on CRT, told me, “It is clear that the discussion or the talking points around having parents have more input into the curriculum” is being used as a euphemism for CRT. “The folks who are anti-CRT are fairly well entrenched, and they hold those sentiments quite strongly,” he said. “What Christopher Rufo is trying to do is make it more palatable to a broader cross section of voters, parents, and Americans generally by talking about parental input into the curriculum.”

In the ALG focus group memo being widely cited as evidence that CRT is just not as big an issue, the researchers did say that participants, even as they conceded critical race theory wasn’t formally taught in schools, talked about feeling “like racial and social justice issues were overtaking math, history, and other things” and “worried that racial and cultural issues are taking over the state’s curricula.”

A Fox News Voter Analysis survey conducted

by NORC at the University of Chicago, which polled over 2,500 Virginia

voters after the election, found a stunning 72 percent of respondents said the

debate over teaching CRT in schools was “an important” factor to them, with a

quarter calling it “the single most important” factor.

This doesn’t fully discount the school-closure explanation. The Fox survey also

found 27 percent of voters ranked “the debate over handling Covid-19 in

schools” as their single-most important issue. But of that cohort, two-thirds

cast their ballot for Terry McAuliffe. Given that the aforementioned Covid-19

debate could encompass masks, vaccine requirements, and virtual schooling, it’s

hard to parse out exactly what’s going on. But the fact that voters who said it

was the most salient for them broke heavily for McAuliffe goes against the

conventional narrative.

Michael Hartney, a political scientist at Boston College, did a postelection analysis for Chalkbeat, where he found Youngkin made slightly larger gains in regions where schools took longer to fully reopen, controlling for the share of Trump voters and white voters in a given area.

He also found that Youngkin did no better in places that had a school district staff member dedicated to diversity, or that mentioned equity in its mission, proxies he designed for CRT.

“The analysis was by no means perfect, but I do think it showed that there is little systematic evidence that Youngkin ran up vote share (relative to Trump) in districts which have more heavily emphasized diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives,” Hartney told me via email, stressing he was doing “merely an exploratory analysis.” Hartney added that he’s waiting on getting some postelection micro-survey data to analyze and tease out some of these patterns more carefully.

Brian Stryker, the ALG pollster, told me he doesn’t know why school closures didn’t come up in Geoff Garin’s postelection survey but maintained they were a big deal in his research. He stressed the importance of candidates and elected officials showing more empathy for the hardship families have faced and continue to face around schools.

“Going to remote learning is deeply unpopular, it just feels like that’s in the ether, it’s the thing that you hear from parents all the time,” he said. (Stryker lives in Chicago, where schools closed earlier this month.) “That’s not a very scientific thing to say,” he added, “but the focus groups and surveys are backed up by every parent that I talk to in my life, and they’re all furious about the closing and all worried their school is going to be next.”

On Twitter earlier this month, Stryker shared a Suffolk/USA Today poll showing 66 percent of the country and 52 percent of Democrats oppose shifting schools to remote learning to contain the spread of omicron. “Hard data to back up what we’re all feeling—closing schools, on top of being an educational disaster, is a political disaster for Democrats too,” Stryker tweeted.

But when I brought up that polls showed most voters, including parents, were not in favor of fully reopening schools before vaccines came out, he agreed that “minds changed around the vaccine, once teachers were getting vaccinated, once grandparents were getting vaccinated.”

Has he found any evidence that leads him to conclude voters will hold Democrats

responsible in November for schools that close during the omicron wave?

“I think 10 months is a long time, and I think parents are pretty

understanding of the fact that people are very sick right now; nobody wants

teachers to go to school with the coronavirus,” he said. “Should there be another

wave that looks like omicron, we may have to reassess, but in 10 months, if

this isn’t still happening, I don’t think it will be a huge voting issue.”