By the time I got to know Jason Epstein, he had already reinvented publishing at least twice—the high-quality midlist paperback and the high-end Library of America—and had helped launch one of the most influential instruments of American intellectual life, The New York Review of Books. Back on a winter’s day in 2003, Epstein wanted to meet me to wax prophetic about his new vision for American publishing.

“Returns.” Epstein repeated to me, “Returns are killing the houses and giving all the power to Amazon.”

I’m not sure why Epstein chose to entertain me that day. I had no power. I was a young NYU professor and a midlist, nonfiction author. I had no special pedigree or powerful contacts. My opinion hardly mattered. Perhaps he wanted to try out his pitch on me, an avid bibliophile with a critical sense of what technology might do for us.

A mutual friend had put us together that day in Epstein’s SoHo loft to discuss the future of book publishing. I had just recently published my first book, in 2001, and was proofreading pages for my second, which would come out in 2004. Having just broken into the business, already I had sensed the ground shifting under me. I was curious about Epstein’s vision after he wrote a piece in 2001 promoting “print-on-demand” as an effective response to the various technical and economic threats to traditional publishing.

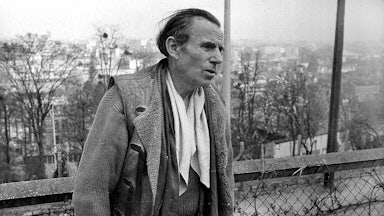

It turns out that Epstein, despite his great success leading some of the major imprints and houses of the twentieth century, was never happy with the establishment or the status quo. He remained a bold troublemaker. I, at 36, was worried about the future of publishing. But Epstein, then 74, was bullish and brash.

Epstein met me at his elevator door wearing a chef’s bib apron. This, I learned, was his standard uniform now that his major public writing was food-related, as a columnist for The New York Times Magazine. He guided me into his kitchen, made me an espresso, and proceeded to cook an omelet for me. He never asked if I were hungry, if I ate eggs, or even if I liked omelets. He was going to make it. So he did it. I was going to eat it. So I did. I was grateful. It was delicious. We spoke for hours. Or rather, he did. I sat back, eating and sipping four more espressos, as he told stories of sad writers and sharp editors and stupid businesspeople he had known.

Epstein was convinced that publishers could take back command of their own distribution and serve bookstores better by embracing a new technology that would limit the production and storage of surplus books for which no demand existed. And thus, publishers could insist that stores cease ordering excess copies, only to return the unsold copies at a loss to the publisher—and only the publisher.

This had to change, Epstein concluded. It should have changed decades ago. But now it could and would. With networked machines that would print and bind books with decent levels of quality—perhaps lower than the library-level cloth hardback but above mass-market paperbacks—in the back room (or even front) of thousands of bookstores across the world, no store would have to display more than one copy of a book. While stores could continue to distinguish themselves by specializing and relying on expert staff and local knowledge to guide customers, any store could produce any book within five minutes.

Neither digital piracy nor Amazon nor digital readers would crush publishers or bookstores if they would just listen to him and make the right move now, he promised. I probed and pushed back against his optimistic assessments. I tried to find weaknesses in his analysis. I failed. I left his place convinced that he had the best vision for the future of books, readers, and writers.

I doubted the rest of the world would come around to share his vision in time, but I could not doubt Epstein’s commitment and energy. Always a businessman, Epstein the next year co-founded a company, On-Demand Books, that produced the Espresso Book Machine. That first Espresso machine debuted in the New York Science, Business, and Industry Library in 2007. It was proof of concept, for sure. It remains just that, displayed in libraries and even some bookstores around the world but still waiting to revive book commerce and culture.

Jeff Bezos might not know how to make a decent omelet. But Bezos can order his engineers to build a million cheap omelet machines and convince the world to consume second-rate food for the sake of convenience. Our addictions to convenience and abundance, as Bezos understands and Epstein did not, would soon undermine everything good. We are condemned to live in the flavorless world Bezos built for us. But Epstein’s world would have served us better.