This week, the jury adjudicating former vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin’s defamation suit against The New York Times ruled in favor of the Gray Lady, temporarily alleviating the worry among journalists that the case might harm press freedoms. It was an intriguing ending: As the jury deliberated, Judge Jed Rakoff announced that he was dismissing the case on the grounds that Palin had failed to meet the high standard for defamation.

He decided to allow the jury to reach their own independent conclusions with an eye toward a potential appeal. And even though Rakoff chose to dismiss the case, he did not entirely dismiss Palin’s concerns—nor did he forgive the Times’ error that touched off the whole hullabaloo. In this way, Rakoff has given journalists a teachable moment.

The case stemmed from a June 2017 editorial titled “America’s Lethal Politics,” pegged to a gunman’s terrifying attack on Republican lawmakers at a baseball field. The primary author of the piece, Elizabeth Williamson, testified that she had delivered copy to James Bennet, the Times’ opinion page editor at the time, who substantially rewrote it. In an effort to zazz up the piece, Bennet introduced an error: a suggestion that campaign ads from Palin’s super PAC had “incited” Jared Loughner’s 2011 assassination attempt on Representative Gabby Giffords. By the time it was published, this alleged connection had been widely debunked. The error-laden editorial landed crosswise almost as soon as it was published; a correction was made, but Palin did not find it adequate.

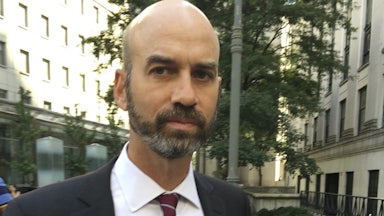

The Times provided another belated remedy to Palin’s claim: As of June 2020, it no longer employs Bennet. Bennet’s eventual fall from grace followed another embarrassing blunder, when he agreed to publish an op-ed from Senator Tom Cotton titled “Send in the Troops.” In the piece, the senator used the Times’ platform to launder his previously expressed opinion—that Black Lives Matter protesters should be shown “no quarter” (a phrase conservative attorney David French likened to a war crime)—into something more palatable. It also made assertions that Bennet’s own paper had already proven to be false. A more attentive editor, aware of current events, might have caught the fact that Cotton had failed to reconcile his previous position with his new one. It turned out that Bennet had not read the piece, which was the seed of his undoing.

But that seed had sprouted long before this incident, and observers had cannily warned of Bennet’s wayward editorship years prior to his dismissal. As Gawker editor-in-chief Leah Finnegan, then writing for The Outline, put it in 2017, “This guy loves to troll and position his writers as martyrs for their bad opinions. He also seems kinda bad at the basics of his job (writing and making sure facts are correct).”

Another moment of Bennet’s tenure, from 2019, stands out as an example of his worst tendencies: his decision to publish Times columnist Bret Stephens’s piece, “World War II and the Ingredients of Slaughter.” As with the Palin editorial, there was a tortured backstory: In late August of that year, a George Washington University professor named Dave Karpf tweeted a joke in response to news that the Times was dealing with a bedbug infestation, “The bedbugs are a metaphor. The bedbugs are Bret Stephens.” Karpf, being of little renown, attracted scant engagement from his tweet. But the matter blew up into full view after Stephens, who caught wind of it, sent an angry email to Karpf’s bosses, thus ensuring that a wider universe would become aware of Karpf’s joke and Stephens’s thin skin.

All might have ended right there had Stephens been under the care of another editor. Sadly, he wasn’t, and it didn’t: A few days later, the Times published an opinion piece in which Stephens likened Karpf to Nazi propagandists. The piece was treated as an instant embarrassment upon arrival, and justifiably so.

The editorial mistakes at play in both the Palin op-ed and this Stephens effort share something in common, something that writer Tom Scocca identified in a recent postmortem on the Palin defamation case: In both instances, the pieces required substantial factual back-filling to justify their existence. For these zany ideas—Palin incited murder; Dave Karpf is a latter-day Leni Riefenstahl—to stand on their own, Bennet’s opinion section needed to hustle up some facsimile of substance to “reverse-engineer the facts” and buttress a “feeble argument.” The premises of each piece were plucked from the thinnest of air, driven by a desire to ascribe deeper meanings that weren’t there; to achieve a grandiosity that reality could not support.

This is a meaningful lesson for everyone who traffics in opinions and ideas: The news of the day doesn’t always allow for deeper connections to be made, or a unified field theorem to assert, and the pursuit of such baubles can lead to embellishment, benign and malign. It’s a lesson that, I fear, won’t soon be learned.

Just last weekend, CNN published an absurd piece from writer John Blake that sought to connect podcaster Joe Rogan’s previous use of racial slurs to the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol. A responsible editor should have headed this idea off at the pass. On display were the same wan premises, the same manipulated-to-support-a-specious-idea grasping of thin facts, the same need to derive something more exciting than the real news on offer, and the same impulse to troll. It gives me no pleasure to note that it also provides Rogan’s lawyers a path to follow in the footsteps of Sarah Palin’s lawsuit. And if this kind of journalism prevails, we could continue to see the consequences, on the page and in the courtroom.

This article first appeared in Power Mad, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Jason Linkins. Sign up here.