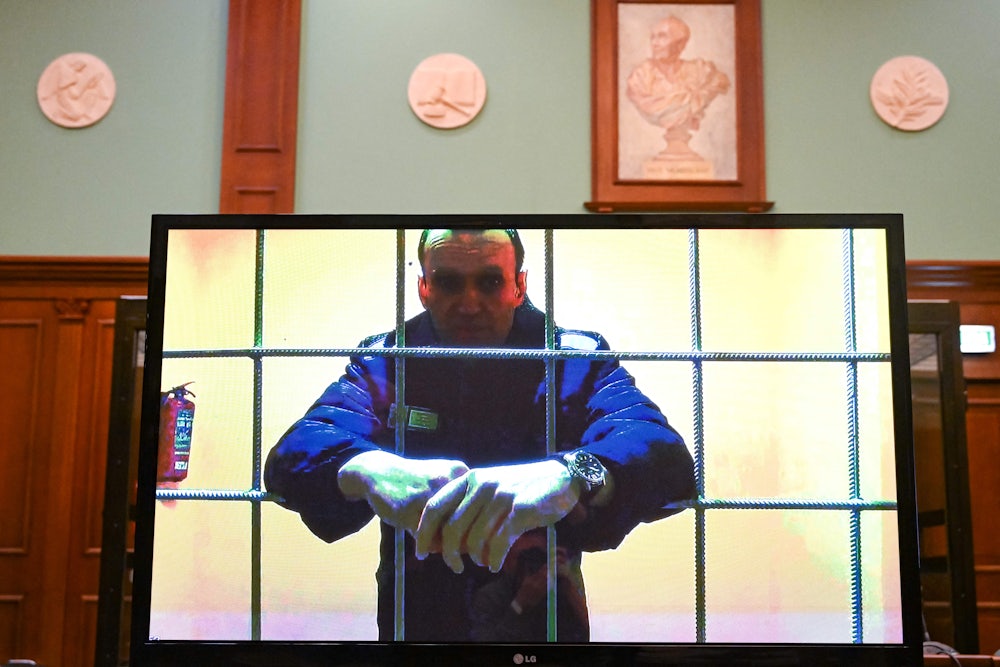

For a man locked in a prison cell in a country that (like the

United States) is not known for treating its prisoners particularly well, Alexei

Navalny manages to keep busy. The opposition leader meets with lawyers five

times a week, but there isn’t much of a legal case—in March, he was sentenced to nine more years

for fraud and contempt of court (added to his two-and-a-half-year sentence),

as part of what Amnesty International calls a campaign of “state-sponsored

harassment and prosecution for exercising his right to freedom of expression.”

Instead of hoping for leniency from the rigged court system, Navalny uses his

meetings with attorneys to strategize and pass messages, which become his

official statements on social media and to the press.

And now, under his auspices, his Anti-Corruption Foundation (known by the Russian acronym FBK) has published a list of 6,000 individuals with ties to President Vladimir Putin’s government who the organization says should be sanctioned. It is “a list of warmongers—members of Putin’s elite, whose actions made the insane war against Ukraine possible,” according to FBK’s chief of staff. The roster of “bribetakers and warmongers” includes members of Russia’s security council, state media, governors, election organizers, judges, and artists.

Navalny and the FBK are pushing for sanctions not only because they believe those listed merit opprobrium but because they are hoping that the 6,000 will distance themselves from Putin, causing a chain reaction that will isolate and eventually bring down the government and entire system. “This regime is a brittle regime, so [it’s] very strong, but when it breaks, it breaks,” said Jamison Firestone, an American-born lawyer who has been active in Russia for decades and works with the FBK.

If individuals with close ties or loyalty to Putin are sanctioned, the thinking goes, they may feel their allegiances to the leader are costing them more than benefiting them. If they quit or, better yet, publicly criticize the regime, they can induce others to do the same. “Do that in numbers, and it will have an effect,” says Firestone. It’s a bold, innovative strategy. Could it work?

The track record of sanctions leading to regime change—as opposed to behavioral change—is dismal. Cuba, North Korea, and Iran have been under sanctions by the U.S. and sometimes its allies for decades, with little to show for the efforts beyond impoverishing the citizens of those countries. In the 1990s, policymakers made it clear that sanctions against Iraq wouldn’t be lifted until Saddam Hussein was out of power, and that coercion also failed.

But the FBK believes Russia would be different. Unlike other heavily sanctioned countries, such as, say, Syria, Russia has a large network of powerful high-net-worth individuals. Once members of this sizable circle of wealthy and well-connected individuals find their finances targeted, they may conclude Putin’s costs to them outweigh his benefits. “The sanctions really haven’t taken their big bite yet,” says Firestone.

To some extent, lawmakers have already been employing this strategy, on a smaller scale. “The concept itself, I think, is in line actually with previous U.S. sanctions programs,” says Christopher Miller, a Russia historian at Tufts University. For the last decade, the departments of State and Treasury have penalized individuals complicit in Putin’s rule, in the hopes that they’ll abandon their ways.

But pushing for the fall of the entire regime with these penalties is arguably a difference in kind, not just degree. Russia is now the most heavily sanctioned country in the world, and the sanctions have been implemented in such a short period that their effects are unpredictable. “Western sanctions are the toughest measures ever imposed against a state of Russia’s size and power,” the historian Nicholas Mulder wrote in March—and additional penalties have been added since then. More are likely forthcoming. The European Parliament passed a resolution calling for the European Council to increase existing sanctions and introduce new ones, “taking into account the list of 6,000 individuals presented by Navalny’s Foundation,” the resolution says.

Despite Putin’s murderousness, if Navalny’s gambit somehow worked and caused the Putin regime to fall, it cannot be assumed that his successor would necessarily be someone liberal-minded. Anybody who replaces Putin would likely be in the same circle, someone who is like-minded and believes Russia’s policies are justified. “Their hands are all tainted by this war,” says the City College of New York’s Rajan Menon, author of several books on Russia, Ukraine, and the Soviet Union. He says that if there were a popular overthrow of the government that led to democracy, it would be Russian democracy, not one necessarily designed or implemented to the liking of the U.S.

Indeed, for all his courage and opposition to both Putin’s corruption and the war in Ukraine, Navalny himself has made bigoted statements about Georgians (he supported Russia’s 2008 war against Georgia), Muslims, and others who are not ethnic Russians. Couple that with the reality that, as Menon says, a power vacuum if Putin left could be the most dangerous scenario of all, just as Saddam Hussein’s downfall eventually led to the emergence of ISIS. “In the history of the nuclear revolution,” says Menon, “we have never had to negotiate or even think about upheaval and violence in a nuclear-armed state, let alone one the size of Russia.”

And yet Putin’s actions have been so brutal that the burden of proof lies with those cautioning that stability is beneficial. “That argument had more evidence behind it, or more logic behind it, before the war,” says Miller. In addition, the war in Ukraine has clearly gone worse than the government expected, which might conceivably lead to a rethinking of aggressive Russian policies. “The regime seems under stress,” says the nonprofit Rand Corporation’s William Courtney, formerly a diplomat working in Russia and surrounding countries.

The sanctions will lead to declining living standards, even for elites, who may be unable to find relief in a Europe that has begun to isolate them, Courtney says. “The bearish economy is just going to pressure them, as long as Ukrainians continue to fight and continue to use Western military aid effectively, which they have done remarkably well so far.” Courtney believes that any internally directed regime change would lead to a more liberal government, since that would be the only way Russians could rid themselves of the crippling sanctions.

States have demonstrated an incredible ability to withstand punishments in pursuit of their national objectives, however. Nationalism is such a powerful force that it can lead citizens to rally around their leaders when they are criticized or punished by foreigners. The Navalny Foundation admits that Putin has sufficiently coopted, isolated, or repressed any dissident forces that could conceivably cause his downfall. Says Firestone: “It’s not like it’s going to collapse in one day.” But from his prison cell, Navalny is hoping that, with enough outside help, the flunkies and hangers-on who aid and abet Putin will see that they would be better off no longer aligning themselves with the most hated man in Eurasia.