The official Defense Department definition of terrorism—“the calculated use of unlawful violence or threat of unlawful violence to inculcate fear … in the pursuit of goals that are generally political, religious, or ideological”—turns a stunning and largely verboten conclusion into an undeniable banality: The dominant Trump-cult wing of the American right is a terrorist movement. Only a minority of Republican voters behave violently, but Republican leaders in Congress, and the most influential right-wing media personalities, routinely refuse to condemn violence, acting as if far-right terrorism is insignificant.

Given that the U.S. military asserts that the mere threat of violence to achieve political ends constitutes terrorism, it is safe to say—with acts like the kidnapping plot against Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, death threats against election workers and librarians, and of course the January 6, 2021, insurrection—that Americans are currently living in an age of terror.

A spate of recent books attempts to dissect the escalating violence and fascism of contemporary right-wing politics in the United States. Most of the authors, ranging from Vanderbilt University historian Nicole Hemmer to former Republican Party consultant Stuart Stevens, have asked some version of the question that troubles millions of voters: “How could this happen?”

One of American history’s most devastating and significant but little discussed assassinations offers an answer to the mystery.

Harvey Milk was a Jewish American Navy veteran from New York who moved to San Francisco in 1969 to acquire personal freedom and financial prosperity. Through a steady evolution of political priorities that doubles as a reluctant hero’s journey, Milk eventually became the “Rosa Parks of the gay rights movement,” to quote longtime San Francisco journalist Mike Weiss—leading the charge for civil liberties, business opportunities, and political power. After three losing campaigns for office, Milk became California’s first openly gay elected official in 1977, winning a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. He and George Moscone, at the time the most leftist mayor in the city’s history, promised to remake San Francisco according to the demands of the popular movements and cultural changes of the decade.

Against the oppressive influence of the Catholic Church and the local police department, the hippies of Haight-Ashbury, the gay activists of the Castro neighborhood, and various other young liberals transformed their city in the 1960s and ’70s from one where cops regularly raided gay bars, beating and arresting patrons, and where officials routinely consulted the Archbishop before making decisions, to the epicenter of the sexual revolution. With the election of Moscone and Milk, those activists moved from the streets to City Hall. Milk and Moscone pledged to aggressively represent the interests of previously exiled constituents: gay and trans residents, Blacks, Chinese immigrants and Asian Americans, and the poor of all racial backgrounds and sexual orientations. Police reform, measures aimed at hospitality and inclusivity for an increasingly diverse polity, zoning laws to protect a “city of neighborhoods” from corporate capture, and progressive changes to the municipal tax code were on the agenda.

Moscone and Milk’s most strident opponent was Dan White, another supervisor and a former police officer, who represented a predominantly white, conservative Catholic district on the far, southeastern edge of the city. In the beginning of their respective terms, Milk and White formed an odd friendship. Despite their severe political differences, they both saw themselves as the board’s sole representatives of a beleaguered social group—LGBTQ citizens in the case of Milk, and for White, a pious and reactionary constituency in a city becoming more liberal by the day. Several of Milk’s friends and staffers believed White, who had articulated many homophobic positions, was a dangerous man, but Milk saw him as more “ignorant” than menacing. He was convinced that education and patience could open White’s mind to a more modern and reasonable worldview.

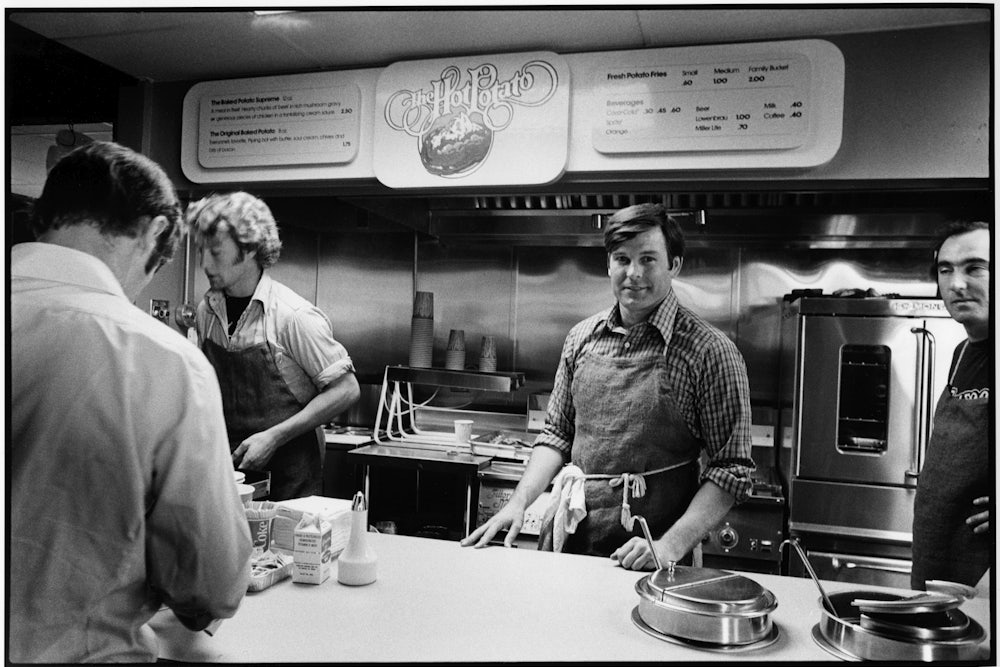

White was not the only advocate of strict pro-business policies on the board, but after voting on the losing side of tax increases and an ordinance protecting gays from hiring discrimination, White would often become angry during meetings, even screaming at Milk and other liberals. The anger intensified when he was found in violation of a charter prohibiting board members from operating a business while in municipal government. He was forced to shut down his baked potato stand.

As White became more isolated on the board and within San Francisco politics, his behavior grew increasingly strange and threatening. Milk began to distance himself, telling confidants that he had misjudged his colleague; he was dangerous. The final blow to the already fractured relationship came when Milk voted for the establishment of a mental health facility in White’s district, breaking a promise he had once made to White to vote in opposition. White accused Milk of betrayal, but Milk insisted that it wasn’t personal. His support for the mental institution, which mainly provided care to adolescents, was sincere. White never forgave Milk, and he exercised a vendetta that complemented his own reactionary ideology. He voted against most initiatives that Milk supported and took a more hateful tone against any cause or event related to gay liberation. Charles Morris, the publisher of a San Francisco gay newspaper, recalled “chills going down his spine” when he asked White if he was “anti-gay.” White turned cold, and said, “Let me tell you right now, I’ve got a real surprise for the gay community.”

Personally depressed and politically enraged, White resigned from office. The Board of Realtors and the Police Officers’ Association—White’s biggest supporters—summoned him to a meeting and convinced him to withdraw his resignation. Initially, Moscone indicated that he would reappoint White to the Board of Supervisors, but under political pressure from Milk and other liberals in City Hall, he later announced that White would not regain his seat.

White’s next move transpired on November 27, 1978. Late in the morning, he sneaked into the municipal government building through a window in order to evade metal detectors. He requested a meeting with Mayor George Moscone, pleading with the secretary for one more chance to make his case for reinstatement. An aggravated Moscone begrudgingly escorted White into his office. When the mayor turned his back to pour a drink, White assassinated him with his police-issued revolver, firing a fatal shot to the head. As Moscone took his last breaths, White walked down the hallway, reloaded his gun with hollow point bullets, located Harvey Milk, and murdered him in cold blood, shooting the gay rights hero five times, twice in the head. Only months earlier, Milk had recorded a cassette tape detailing his life story and political philosophy, leaving instructions to his staff to play “in case” of assassination.

Milk became a martyr for the gay rights movement and has a rightful place in the pantheon of progressive heroes in the U.S. Sean Penn won an Academy Award for his exhilarating and tender portrayal of Milk in the 2008 biopic, which also won an Oscar for best original screenplay. The late Randy Shilts’s biography, The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk, is a classic of the genre, effortlessly blending sociopolitical analysis with a deeply moving chronicle of an extraordinary life.

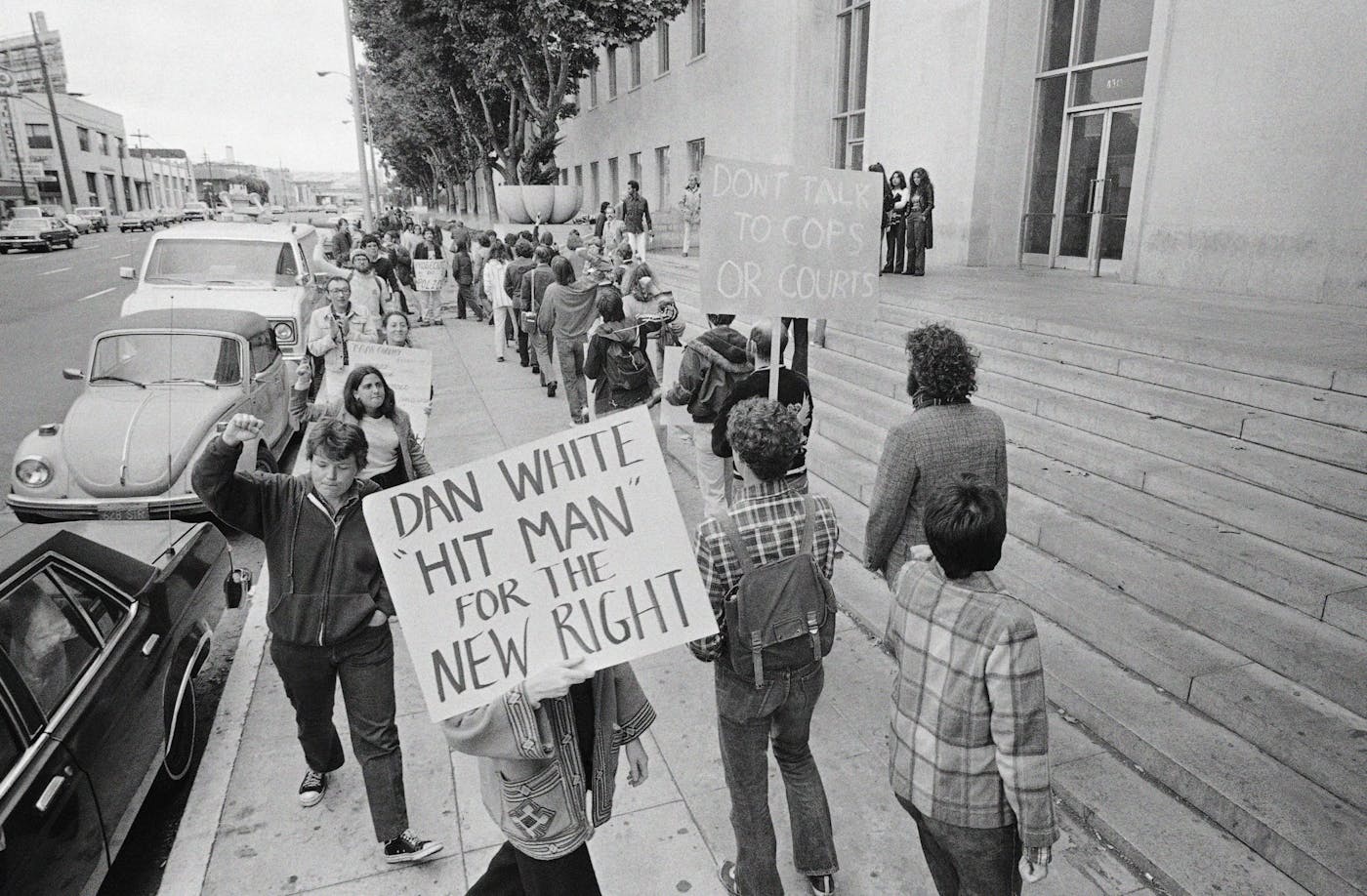

Despite the celebration of Milk, American historians, journalists, and political commentators have largely ignored the dark insight that White’s act of terrorism affords us into the paranoia, malevolence, and danger of the American right. White’s criminal defense, and the sympathy it garnered, foreshadowed what the Republican Party, and its various anti-democratic satellite networks of support, have become in 2022.

Only

days after the murders, police officers adopted “Free Dan White” as a slogan,

often shouting it on the streets, and even wearing it on T-shirts underneath

their uniforms. The San Francisco police and fire departments collectively

raised $100,000 for White’s defense fund. Across the city, journalists spotted

graffiti with messages like “Kill Fags: Dan White for Mayor.” Hate crimes

against gay and trans residents exploded, often with the police turning a blind

eye or even committing the assaults themselves. Several cops beat

transgender tenants in a hotel lobby. When the manager complained to a

sergeant at the nearest precinct, the officer said, “Well, they’re only

fruits.”

Police treatment of White, a double murderer who had quickly confessed to his crimes, stood in stark contrast to the persecution of law-abiding LGBTQ Americans. Jailers allowed White special privileges, including meals from his favorite restaurants and pastries baked by admirers. In fact, the most infamous aspect of White’s defense at trial involved his sweet tooth. Defense attorneys claimed that White had spent days binging on supermarket cakes and cookies, causing an excessive amount of sugar to rob him of his rational faculties. The medically absurd assertion is now known as the “Twinkie Defense.” It is the other element of White’s excuse for assassinating his political adversaries that exposes how a fundamental aspect of right-wing ideology is contradictory to democracy, because it posits that progressive change is more dangerous than authoritarian persecution and violence.

After eliminating anyone who claimed to support gay rights from the jury pool, White’s defense team presented its client as a heroic, “real” American—a military veteran, former police officer and firefighter, devout Catholic, and committed family man—juxtaposing him with the socialists, atheists, and gay hedonists who were destroying San Francisco and attacking the “values” of “traditional America.” Warren Hinkle, a San Francisco journalist, was one of the few writers with the clarity of vision to understand that White wasn’t merely a disturbed malcontent with an addiction to sugary snacks. He was an agent of a political project, speaking and acting on behalf of constituents who opposed the “gay invasion” of their city and a corrupt police department that enforced the hierarchal rule of wealthy, reactionary white heterosexuals against Blacks, Chinese, and the growing gay liberation movement. The assassinations weren’t even his first hate crimes. Hinkle learned that White would regularly invite white-supremacist street gangs to town hall meetings so that they would intimidate his opponents into silence. In an ultimate perversion and vicious application of an “ends justify the means” philosophy, White’s defense rested on the fascist notion that violence is acceptable, even laudable, if committed to protect “conservative America” against democratic change.

When the prosecution played a tape of Dan White’s confession during the trial, four of the jurors cried tears of sympathy. The alarming moment functioned as a preview of the verdict. White was convicted not of murder but only of the charge of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to just seven years in prison. The jurors who spoke to the media explained that they believed White was a “good man” and that prayer had led them to their decision. When police officials heard the news, they played over the scanners the traditional ballad “Danny Boy”—a paean to an Irishman who participates in a political uprising.

San Francisco gays and their supporters rioted that evening. But ultimately, the gay rights movement overcame the murder of Milk, transforming American politics, culture, and law for the benefit of millions of people. Few scholars or social critics seem to spend much time thinking about the White catastrophe, even if it is emblematic of the nationwide threat facing democracy. As Shilts noted in his biography of Milk, for all of the stories regarding the “kookiness” of San Francisco, rarely is there any mention that “the killer who had caused the city’s major tragedy was spawned not in a hippie commune, but from such all-American institutions as the Catholic Church, the U.S. Army, and the police and fire departments.”

One pundit who appears not to have forgotten Dan White is Tucker Carlson. The chief propagandist for the neo-fascist movement claimed in his 1991 Trinity College yearbook that he was a member of the “Dan White Society.” No such organization existed, but that Carlson would find that “funny” is plenty revealing of how central homophobia is to America’s leading Viktor Orbán champion.

In the past year, state legislatures across the country have proposed approximately 240 anti-LGBTQ bills, and Republican politicians regularly liken gay and trans teachers, government employees, and librarians to pedophiles. After steadily rising since the political emergence of Donald Trump in 2015, targeted murders of LGBTQ citizens reached their highest point on record in 2021. The American right has not only turned against its gay and trans compatriots. It’s become hostile to the mechanism that empowers them: liberal democracy.

Just as Dan White himself sought to destroy the democratic process and violate the will of the people, members of the mythic Dan White Society—that is, the inheritors of his hatred and violence—are working overtime to impose their bigotry and authority on the U.S. If they cannot triumph by electing officials who will weaken the institutions, checks and balances, and minority protections necessary for democracy to thrive, they will resort to violence. The insurrection of January 6, the deification of Kyle Rittenhouse, and the popularity of gun-wielding, thuggish extremist groups interlock to form a hideous picture of the right wing’s political ambition.

Five members of the Proud Boys, a “Western chauvinist” hate group instrumental in the events of January 6, now sit on the GOP Executive Committee of Miami-Dade, the most populous county in Florida. Their success is not surprising or aberrant. Robert Pape, a University of Chicago professor who specializes in the study of terrorism, has determined that 21 million right-wing Americans believe that the use of force is justified to achieve political aspirations.

Suffering from delusions of persecution and grandeur, they believe that they are saving the U.S. from the devious plots of “globalists,” “sex traffickers,” and oppressive “cosmopolitan elites.” They are attempting to preserve a down-home, patriarchal, Christian America that never truly existed. It is a condition that Albert Camus diagnosed in his treatise on counterculture and political revolution, The Rebel.

Like

the executors of the Dan White legacy, the fascist revolutionary or terrorist

“imagines himself a romantic hero,” in the words of Camus, “compelled to do

evil for an unrealizable good.”