Alaskans face several critical decisions in this year’s midterm elections, voting on the reelection efforts of their sole representative in the U.S. House, a Democrat and the first Alaska Native in Congress; a moderate Republican senator facing a Trumpian opponent; and a hard-right GOP governor. Thanks to redistricting, 59 of the state legislature’s 60 seats in both chambers are also up for election.

But Alaskans face another important choice at the ballot box this year, one that is brought before them every decade but has earned new weight in recent months: whether to hold a constitutional convention to revise the state’s founding documents.

Nearly 70 years ago, dozens of delegates from across Alaska gathered in Fairbanks to write the state constitution. The document, written over three months in 1955 and 1956 and approved by the people in April 1956, became operative when Alaska achieved statehood in 1959. Many of the members of the delegation, which was comprised of 49 men and six women, were World War II veterans eager to earn representation in the country they had served. They pulled what they saw as the best elements of other state constitutions, adapting provisions for the unique dynamics of Alaska.

“They wanted a document that would be brief and broad by design, so that a young state could grow, that rights would be protected,” Cathy Giessel, the former president of the Alaska state Senate, told me. Giessel is on the executive committee of the group Defend Our Constitution, which opposes a constitutional convention.

Included in the state constitution is a section providing for Alaskans to vote on whether to hold a constitutional convention every 10 years. There are other ways to change the state constitution: The document has been amended 28 times to include provisions such as a right to privacy and the prohibition of gender discrimination. But in Alaska’s 63 years in operation, there has never been a convention to change the constitution wholesale. (Alaskans have voted to hold a convention only once, in 1970; the vote was overturned in court due to misleading ballot language, and the question was voted down when it came before voters again two years later.)

The question of whether to hold a constitutional convention has typically been voted down by wide margins. But this year is different, thanks to concerns about Alaska’s ailing fiscal situation and preservation of abortion rights. “No time in my 30 years in politics have we needed to rise to this level of effort,” said Joelle Hall, the president of the Alaska AFL-CIO and member of the Defend Our Constitution executive committee.

The argument against holding a convention largely boils down to this adage: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Holding a convention would be time-consuming and costly, opponents say, and invite instability into state politics at an already polarized moment. If Alaskans did vote in favor of a constitutional convention, the state would likely then vote to choose delegates in 2024. Cost estimates vary widely, but the range is roughly between a few million dollars and $20 million. Delegates, who could also be sitting legislators, would have plenary power, meaning that they would have the authority to start the constitutional process from scratch.

“If they wanted to, they could take a blank piece of paper and start all over again. Literally every single article is up for debate,” Hall said. “When people understand the totality of it, they’re starting to understand the risks.”

Alaska is in a unique position in terms of geography and resources, which in turn affects its finances. In 1976, the state amended the constitution to place a portion of the revenue generated from oil into a dedicated fund: the Permanent Fund. A portion of the fund is used for the Permanent Fund dividend, an annual payment to Alaskans generated from these investment earnings. (There have been some major fights over the Permanent Fund dividends in recent years; in the interest of time I will invite you to read some of the great reporting on the matter from The Anchorage Daily News.) Hall called the issue of the dividend, which is not protected by the state constitution, “the nuclear charge in the middle of this whole conversation.”

The Permanent Fund dividend has been a focus of Convention Yes, a group formed in August that is in favor of holding a convention; some supporters hope to enshrine the dividend in the constitution. But opponents argue that concerns about the dividend are a smokescreen and that the real agenda is to insert conservative priorities into the revised founding documents.

Jim Minnery, a conservative Christian and the president of the Alaska Family Council, told me that his “number one issue” is the judicial selection process. While the Permanent Fund dividend is “the primary driving force that is getting Alaskans fired up,” Minnery said, his and other organizations are also focused on the social implications of a convention. Under the current system, the Alaska Judicial Council—an independent commission composed of three attorneys and three members of the public, with the chief justice of the state Supreme Court serving as chair and tie-breaking vote—sorts through applicants and presents a pool of potential judges to the governor, who chooses one to fill a judicial vacancy. Alaska is one of 26 states to use this process to select judges.

Minnery, who is on the steering committee of Convention Yes, argued to me that conservative executives, like current Governor Mike Dunleavy, should be able to select conservative judges. “I think many Alaskans are fed up with that and want to have more say in the government,” Minnery said.

Abortion rights are connected to the issue of judicial selection, particularly in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade in June. Without the federal right to an abortion, Alaska could become a state where abortion restrictions are imposed—but a motivated legislature needs a supportive judiciary. (Convention Yes has not campaigned specifically on abortion.)

Alaska state courts have upheld abortion rights and stricken down some restrictions, citing the clause in the state constitution protecting the right to privacy. “One of the primary motivating factors for a lot of pro-life Alaskans is that our court has manufactured a right to abortion out our privacy clause, which is not there, it’s just made up out of thin air,” Minnery said. “It needs to be clarified that our constitution is silent, or neutral, on the issue of abortion.”

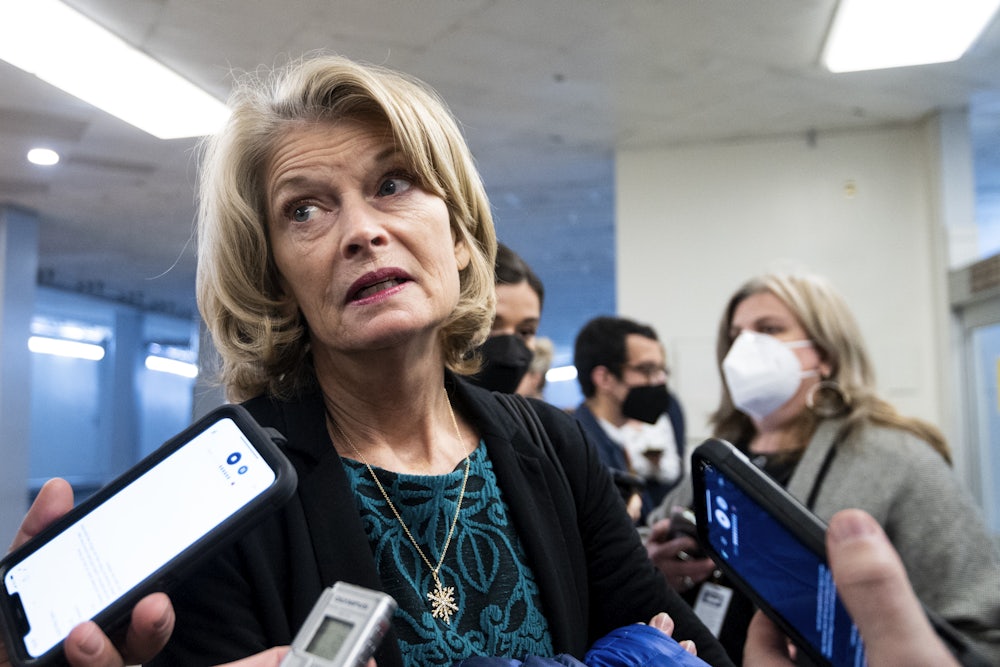

However, abortion rights are broadly popular in Alaska. Sixty-three percent of Alaskans believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to the Pew Research Center. One of Alaska’s two Republican senators, Lisa Murkowski, supports abortion rights; its sole representative in the House, Mary Peltola, proudly identified as “pro-choice” in her successful campaign to win the August special election to replace the late Representative Don Young. Abortion rights supporters therefore believe that the issue can be a potent motivator for Alaskan voters.

“It feels like the really strong right-to-life crowd here can rail against choice, put forward all kinds of unconstitutional actions and bills and lawsuits, and there’s a backstop. They can howl at the moon, but nothing’s going to change. Now, this group that’s been howling at the moon and changing nothing could conceivably get many delegates,” Hall said. “There is no guarantee that we can elect 65 percent of the delegates that would represent the values of Alaska being a pro-choice state.”

Defend Our Constitution itself is a broad coalition and therefore is also not campaigning on abortion. One of the members of the steering committee, former Republican state Senator John Coghill, is strongly opposed to abortion rights. The Planned Parenthood Alliance Advocates of Alaska, the American Civil Liberties Union of Alaska, and the Alaska Center Education Fund have been working together in canvassing efforts to urge Alaskans to oppose the constitutional convention question, said Rose O’Hara Jolley, the Alaska state director of Planned Parenthood Alliance Advocates.

“It felt like the piece that was missing was direct voter contact, so getting on the phones and getting on the doors and talking directly to voters about how important this is from the lens of abortion access specifically,” O’Hara Jolley, who uses they/them pronouns, said. They said that, even when knocking on doors without targeting specific voters, around 80 percent of respondents said they would oppose a constitutional convention “once they found out that abortion was at risk.” That percentage was even higher once canvassers started targeting voters: “Even if they hadn’t known what it was, or had maybe thought that they were going to vote ‘yes’ for various reasons, very quickly once they saw that abortion was at stake, they were like, ‘We will vote no.’”

Aside from the abortion rights issue, Giessel raised concerns that a constitutional convention could result in economic instability and invite actors from the Lower 48 to try to meddle in state politics. “There are a lot of organizations outside of Alaska who see us as a place that has a small population and [is] very able to be influenced,” Giessel argued. “We foresee that a lot of outside influences, in the form of outside money, would pour into the state, each with their own interests that they would be promoting.” She also contended that, during the years-long process of the convention, businesses may not be willing to invest in Alaska.

But supporters of a convention counter that there are already outside influences factoring into this debate, pointing to the three biggest donors to Defend Our Constitution: the nonprofit Sixteen Thirty Fund, the National Education Association, and AFSCME, all of which are based in Washington, D.C. As Minnery noted to me, the Sixteen Thirty Fund has been identified as a dark money group by The New York Times. “It’s not Alaskans, it’s a giant funding source trying to scare Alaskans,” Minnery contended.

Defend Our Constitution has raised considerably more money than Convention Yes, which reported raising around $21,000 and spending more than $24,000 in a recent financial disclosure report. Meanwhile, Defend Our Constitution has received $2.7 million and spent around $1.8 million, with more than $1 million of its donations coming from the Sixteen Thirty Fund. That funding has been spent on paid media, digital ads, TV and radio ads, and mailers. (Just Google the words “Alaska Constitution” right now, and I guarantee you there will be an ad for Defend Our Constitution right at the very top of your search results.)

“We know we can’t compete with that. So we’re just going directly to the people, with town halls, social media, and a little bit of radio and newspaper [ads],” Minnery told me.

A spokesperson for the Sixteen Thirty Fund said in an emailed statement that the organization “supports campaigns and causes across the country.” “We are proud to support Defend Our Constitution. We chose to support Defend our Constitution because an impressive, bipartisan campaign working to protect democracy and civil liberties reached out and made a compelling case about how important this effort was for all of their constituents in Alaska,” the spokesperson said.

Members of Defend Our Constitution believe the funding question is a red herring. The group’s website has a lengthy list of endorsements from Alaska organizations, including several chambers of commerce and several unions, multiple Alaska Native corporations, the Alaska Miners Association, and the Sitka Conservation society. Last weekend at its annual convention, the Alaska Federation of Natives, the largest statewide Native organization, declared its opposition to holding a constitutional convention.

Ira Slomski-Pritz, the campaign manager for Defend Our Constitution, noted that their group was competing for airtime with high-profile federal and statewide races. “We recognized pretty early, just to get our message in our crowded environment, we’re going to need to raise a lot of money,” he told me. “There’s a lot of national groups, for whatever reason, that we’ve been able to make the case to, and they see the coalition that we’ve formed, and they’re excited about supporting us financially. And that’s been the ask. But it’s really been an Alaska-driven campaign.”

There are some prominent politicians on both sides of the issue: Dunleavy is for a constitutional convention, independent gubernatorial candidate Bill Walker and Democratic candidate Les Gara are against it. (One of Dunleavy’s former staffers is also opposed to a convention.) At the Senate debate on Thursday, Senator Lisa Murkowski said she would oppose a convention, as “we have demonstrated that we’ve got a process that works” in the amendment process. The Republican candidate challenging her from the right, Kelly Tshibaka, would support it.

The Alaska Democratic Party passed a resolution against holding a convention, but the state Republican Party failed to approve a motion to support it over the summer. “I really don’t see their candidates getting up and waving the flag for it. We’re seeing a lot more from the ‘no’ on the con-con than we are from the ‘yes’ on the con-con,” Lindsay Kavanaugh, the executive director of the state Democratic Party, told me, using the popular shorthand for the measure.

Polling on the issue has been sparse, but a recent AARP poll found that 46 percent of Alaska voters said they will vote against a constitutional convention, while 30 percent were in favor. But even if Alaskans were to vote in favor of a constitutional convention, there is no guarantee that whatever changes delegates could make would stick: They would vote again on the proposed changes at the end of the process. Minnery argued that this showed the democratic nature of the process, arguing that “you have to trust the people of Alaska.” But opponents would see the potential failure of any changes as years of political and economic instability for no reason.

“In the political environment today, we have become so divided with extremes at both ends of the political spectrum. And if a convention were called, there are so many unpredictable elements that could be introduced,” Giessel told me. “I want stability, I want a prosperous future for our state. And that means keeping this document in a stable, predictable condition.”