A quarter of the way through Ken Burns’s new book, Our America, a plainly dressed woman appears in a photo from the 1880s. She is peering out from the branches and brambles along a road that winds through overgrown countryside, past a split-rail fence and stacked logs. The caption—just a date and location—says that this is Walpole, New Hampshire.

If the woman’s descendants still live in Walpole, they might have first encountered Burns when he moved to the town in 1979. They might have watched as he and his colleagues at Florentine Films issued one acclaimed historical documentary after another, until 1990, when The Civil War broke PBS viewership records and made Burns a celebrity of sorts. They might have seen him become synonymous with the town, as he rose to become one of the most widely viewed and influential documentary filmmakers in the country.

Walpole is still the home of Florentine Films, and it is a crucial part of Burns’s filmmaking. Its distance from the industry, Burns has claimed, allows him and his team to work deliberately and gradually, sinking years into each documentary. Its small-town qualities—its intimacy and neighborly interdependence—have also shaped Burns’s sensibility. His many films represent a single effort to create a shared sense of the American past, to convince Americans that we belong to a sprawling and often turbulent but cohesive community: a nationwide Walpole. This is the civic philosophy that underpins all his work, his long association with PBS, his speeches and interviews and op-eds—even his public persona, which melds amiable dorkiness with a kind of old-fashioned liberal rectitude.

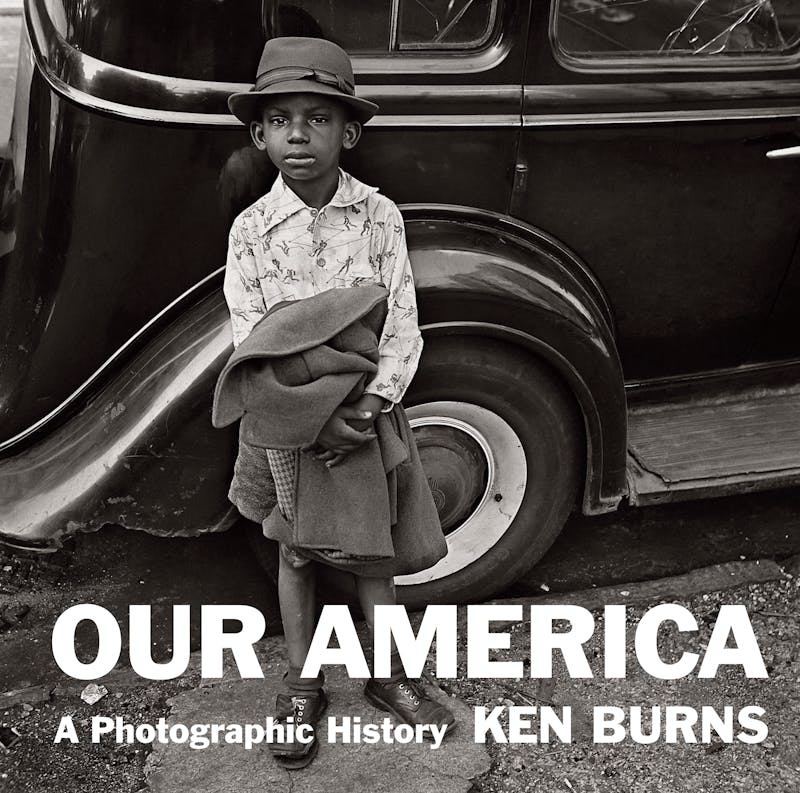

Not everyone who picks up Our America—a tour of U.S. history told through a procession of black-and-white images—will get the Walpole reference. They might consider the next three photos: the Brooklyn Bridge under construction, a Dartmouth College baseball game, and a Shaker schoolroom. These are the subjects of Burns’s first, ninth, and second films. Later, you’ll find Yellowstone national park (his nineteenth film), followed immediately by the Statue of Liberty (his third). The book is littered with his subjects, from Susan B. Anthony to the Central Park Five. Even the obscure Horatio Nelson Jackson—who, with a co-driver and a dog named Bud, made the first cross-country road trip—is here. There’s an abundance of photos from the Civil War and World War II, a good deal of presidential imagery, some jazz, a little country music, and a heap of baseball. Most telling is the photo Burns chose for the dust jacket: an unknown Black child on a New York City sidewalk, wearing a fedora and looking into the lens with wary interest. That photo was taken in 1949 by Jerome Liebling, who would become Burns’s teacher at Hampshire College in the early 1970s and his mentor; the book is dedicated to him and to Burns’s father.

Our America, then, is about a country, but it is also about Ken Burns: a summation, and celebration, of his career. (It was assembled with three co-authors: his Florentine Films colleagues Susanna Steisel, Brian Lee, and David Blistein.) In his introduction, Burns tells us that the book shares the civic mission of his films, that “it was conceived and created in the spirit that assembling photographic evidence of our collective past might help heal our divisions.” The images here do add up to a kind of American self-portrait, one assembled out of momentous events and terrible milestones and glimpses of ordinary life. Stare at these photographs long enough, though, and you’ll be struck by the volatility, the weirdness, and the raw antagonisms that they capture—essential aspects of any honest portrayal of the American past.

There is more than one way to read Our America. You might let your eyes do the work, turn off the historicizing part of your brain, and admire the visual composition of each photograph: the serene grandeur of Orville Wright’s plane floating over the sands of Kitty Hawk, say, or the compressed menace in the geometry of the Ford River Rouge plant. The book is full of such evocative images. But the better way to read Our America is to read it twice: proceed through the photos, then turn to the thumbnails and descriptions at the back of the book and delve into the historical detail of what you see.

Some of these descriptions are genuinely revelatory. That lonesome, tumbledown shack in Tennessee? It sits in the foreground of “Site X,” a uranium enrichment facility for the Manhattan Project. That crowd in Washington, D.C., packed in among huge U.S. flags? They’re celebrating the inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes: underwritten, after a contested election, by the Compromise of 1877, which ended Reconstruction and ushered in a new age of white supremacist terror in the South, a truly pivotal moment in U.S. history.

As an excavation of the past, Our America derives its power from the sheer variety of images and the people and places they represent. These photos are vernacular and mannered and official and spontaneous; they are haunting more often than humorous, sometimes disquieting, and occasionally repellent. They offer no blithe celebration of the country but tend to evoke the wistful moodiness of Burns’s films. There’s a stillness to them. You won’t find much kinetic energy here, and the exceptions stand out: sheriff’s deputies firing into a crowd of striking workers outside of Pittsburgh in 1932, a woman being slapped across the face during a civil rights nonviolence training in 1960.

It may be that Our America seems especially static because Burns is so associated with the roving camera: the “Ken Burns effect,” the visual signature that propels his films. See his most recent documentary, The U.S. and the Holocaust, for a stark reminder of how effective this simple device can be. Burns shows us a photo of German soldiers on the Eastern Front, posing and holding cameras. As his own camera pulls back, we realize what the soldiers are gawking at, and photographing: a hanged man. The purpose of this device—along with Burns’s sound effects and musical cues, his placid narrators and troupe of voice actors—is to nudge us toward specific emotional responses.

Of course, Burns has no such control over how we respond to images printed in a book. Those responses will be more chaotic, less managed, and more interesting. The real movement in Our America happens in the minds of its readers—nebulously, provocatively—when we view the juxtaposition of historically contemporaneous images. What to make of the unnerving and unmistakable visual symmetry between the lynching on an Oklahoma bridge (a photo that was sold as a postcard) and a band of newsies posing in front of the U.S. Capitol? What does it mean to pair Civil War veterans reunited at Gettysburg in 1913 with a child laborer toiling in a Southern hosiery mill?

That last example strikes me as a comment on Burns’s own work. The photo of the Gettysburg veterans also appears in The Civil War, near the end, in a segment about the 1913 battlefield reunion. Some historians criticized Burns for this decision and argued that he had prioritized “the romance of reunion,” as Eric Foner has put it, over other aspects of the war’s legacy. But in Our America, the meaning of that particular reunion is transformed by the subsequent photo, Lewis Hine’s portrait of a child mill worker (taken, significantly, as part of an organized effort to expose poor working conditions). I see this pair of images and think of the post–Civil War reign of industrial capital: how the conclusion of the war and the consolidation of the nation-state meant that capital was unleashed to transform the entire country, but especially the agrarian South, while underpinning the idea of national unity that allowed this process to unfold in the first place. Each of these historical developments made the other possible; each is the other’s cause and effect—and this fuses the two images, the Gettysburg veterans and the child mill worker, into a single concept.

Did Burns plant this idea here, in these two photos? Probably not. But that’s how Our America works. It doesn’t tell the story of the United States through a narrative or a series of arguments. It displays a messy tangle of power and motive, achievement and failure, in a way that’s highly suggestive but also bedeviling. You might pick up on certain patterns in these photos—the centrality of race and dispossession, the majesty of the landscape, the dignity of ordinary people, and even the vitality of photography as a medium. More than anything, though, Burns’s selections insist that any engagement with the American past—indeed, with the very idea of a distinctly American past—means heaping questions upon questions upon questions.

The biggest question, though, might be: What does this book have to do with us? Our America suggests an answer in the essay by Sarah Hermanson Meister, executive director of the Aperture Foundation and a former curator at the Museum of Modern Art. She borrows her title, “A Powerful Monument to our Moment,” from Walker Evans’s elegiac American Photographs, published in 1938, and she writes about Evans and Burns in parallel. But the comparison doesn’t quite stick. Even though Evans and Burns may have created “epic photographic portraits of America,” as Meister puts it, their books are vastly dissimilar: American Photographs is the fully realized vision of a single artist working at a specific time, while Our America is a fragmentary, collective national self-portrait that spans centuries. Meister, to be fair, does recognize these differences, but precisely how Our America might be “a monument to our moment” is somewhat murky. In fact, Burns’s book isn’t really about our moment at all: Our America drops off sharply beginning in the 1970s and ends with only four photos from the entire twenty-first century.

The book seems especially like a retreat from the present when you compare it with Burns’s latest film, The U.S. and the Holocaust. The film explains how a toxic stew of 1930s nativism, antisemitism, and xenophobia aided and abetted the Nazi death machine. It ends with a hectic montage that rushes through the last half-century of white reaction, culminating in Trump, Charlottesville, and January 6. For a Ken Burns film, it’s a shockingly pointed conclusion. There’s no way Burns and his co-directors, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein, will let us miss the lesson. Our America makes no such explicit claim on the present.

The invocation of Walker Evans is apt, though, in a different way. It’s no accident that Burns’s book is full of photos taken by Evans and Dorothea Lange and Gordon Parks and Ben Shahn. All of them worked for the Farm Security Administration, the New Deal agency that deployed photographers to document the impact of the Depression. (Our America is not always accurate when it comes to New Deal–era artistic projects: At one point, the book claims that John Steinbeck and Eudora Welty worked for the Federal Writers’ Project, which is not the case.) The FSA was one instance of a broader documentary trend that gripped the cultural world in the 1930s and ’40s, involving many writers and artists, inside and outside the Roosevelt administration, who sought to capture essential truths about the U.S. by engaging with the particular, the concrete, the actual multitudinous stuff of American life, no matter how bleak or ugly or obscure. Their documentary approach was democratic, inclusive, generous, and emphatically opposed to nationalist mythmaking—especially the fascist variety, the cruel abstractions of blood and soil. It was, in both execution and intention, anti-fascist to the core. Burns belongs to this tradition.

I’m reminded of Ernest Hemingway—the subject of Burns’s thirtieth film—telling the American Writers’ Congress in 1937 that fascism can’t produce good writers. “For fascism is a lie told by bullies,” Hemingway said. “A writer who will not lie cannot live or work under fascism.” You can say the same about documentarians. Our America speaks to our moment precisely because it refuses to lie about the past. The vision it offers is mournful, terrible, exhilarating, and honest—which makes it real. These scenes happened. Burns may not present this as an anti-fascist act, but it is. And while Our America may represent Burns’s plea for unity, it feels primed to clash with whoever would deny the truths on its pages. It has a fighting spirit. That title isn’t a description, but a demand.