The American death penalty continued its long statistical and moral decline in 2022. State governments executed 18 people in the United States this year, one of the lowest totals since the 1970s. Of those executions, roughly one-third could be considered botched, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, or DPIC, a nonprofit organization that studies capital punishment.

“As the systemic flaws of the death penalty have become clearer and more pronounced, it is being regularly employed by just a handful of outlier jurisdictions that pursue death sentences and executions with little regard for human rights concerns, transparency, fairness, or even their own ability to successfully carry it out,” the organization said in its end-of-year report on the death penalty.

Alabama halted executions earlier this year after Governor Kay Ivey ordered a review of the state’s execution policies in the wake of a series of botched executions in that state. One of the prisoners, Joe Nathan James, died three hours after his execution began—the longest such timeline in American history. According to an independent autopsy commissioned by his family and medical experts who reviewed the case, James’s body was covered in bruises and puncture sites where the execution team had apparently tried and failed to insert an IV. He also showed signs of physical trauma and apparent sedation, leaving him unresponsive when brought before witnesses for the execution itself.

Tennessee Governor Bill Lee also announced an independent review of the state’s execution procedures after granting an eleventh-hour reprieve to Oscar Franklin Smith, whose lethal injection was halted due to technical problems. An investigation by The Tennessean newspaper later found that state officials had struggled to follow the procedures and failed to properly store and test the lethal-injection drugs, which could affect their potency and efficacy. Executions in the state are now on hold until that review is completed.

Practical and legal woes have hamstrung execution efforts in other states as well. In South Carolina, for example, state officials found themselves unable to acquire the proper lethal-injection drugs before a scheduled execution in April. State lawmakers instead authorized them to use either the electric chair or the firing squad to carry out the sentences, prompting a lawsuit by death-row prisoners. A South Carolina judge ruled in their favor in September after concluding that the use of either method would violate the state constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

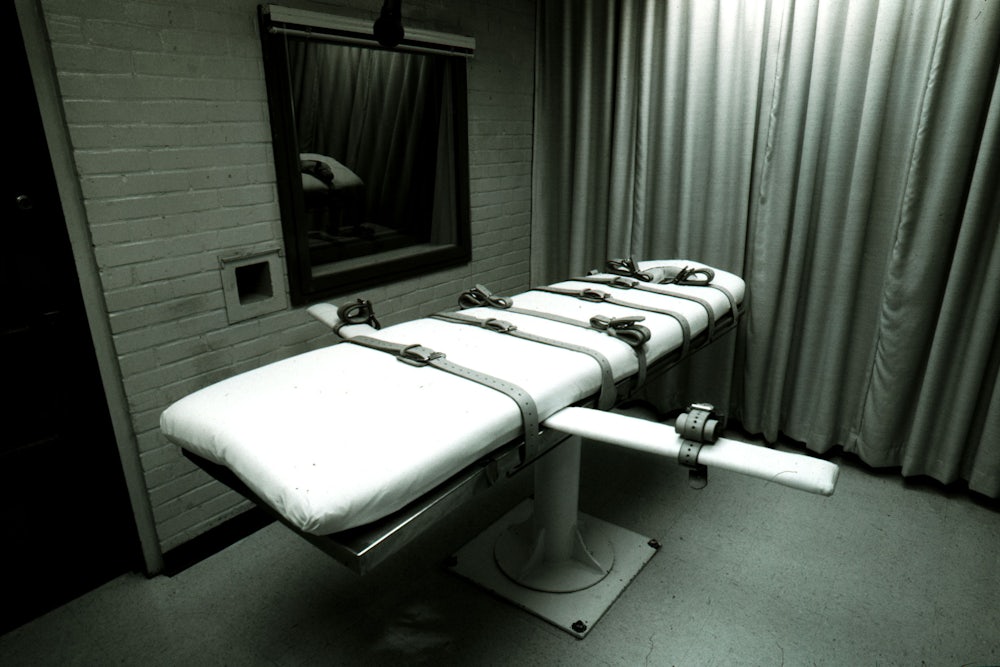

Botched executions have always been a feature of the death penalty in this country. The shift from hangings, which were the default method for most of American history, to the electric chair and the gas chamber in the twentieth century reflected a desire to avoid a gruesome spectacle that could turn Americans against capital punishment itself. Lethal injections, which give the appearance of medical competence and precision, steadily became the norm after the original three-drug cocktail—typically consisting of a quick-acting anaesthetic, a paralytic such as pancuronium bromide, and potassium chloride to induce cardiac arrest—was developed in Oklahoma in the 1970s.

In recent years, that medicalized appearance has been undercut by a series of high-profile errors. The European Union and U.S. pharmaceutical companies imposed an embargo on lethal-injection drugs in the 2010s, prompting states to find less reliable alternatives to carry out executions. A series of high-profile botched executions in 2015 led the Supreme Court to review whether the use of the sedative midazolam violated the Eighth Amendment. The court’s conservative majority not only upheld the use of the drug but made it far harder to challenge the constitutionality of execution methods in the future. Justice Samuel Alito complained at oral arguments that activists had mounted a “guerrilla war” against capital punishment.

That guerrilla war is apparently yielding some results. There are a few different ways to measure Americans’ steady turn against the death penalty. The most obvious one is to just ask them. Gallup’s long-running survey on capital punishment found in October that 55 percent of Americans support the death penalty for murder. Though still a majority, that number represents a 30 percent drop from its peak in 1994, and one of the lowest levels of support since the Supreme Court resurrected capital punishment in its 1976 ruling in Gregg v. Georgia, and a slow but steady downward trend.

Asking people in polling surveys how they feel about capital punishment may also be somewhat abstract. It is one thing to tell a Gallup pollster whether someone should be executed; it is another to sit on a jury and condemn a defendant yourself. The number of new death sentences, which may be a more direct indicator of public enthusiasm, has dropped even more sharply. According to DPIC statistics, American juries handed down just 20 death sentences in 2022. That represents less than a quarter of the death sentences handed down 10 years earlier, in 2012, and roughly one-eighth of the sentences handed down 20 years earlier, in 2002.

It is possible, though doubtful, that Americans are simply committing fewer heinous murders that would qualify for the death penalty. In 1996, when the death penalty was at its post–Furman v. Georgia decision peak, juries across the country sentenced 315 defendants to death. The pool of potentially executable defendants is also smaller than it used to be. Seven states have abolished the practice since 2019. (Nebraska’s state legislature briefly abolished the practice in 2015, but it was brought back in a statewide vote the following year.) Over the last two decades, the Supreme Court has also ruled that states cannot execute juvenile defendants, people with intellectual disabilities, or those convicted of non-homicide offenses. (The federal government can still seek death sentences for treason, espionage, and the like, but such prosecutions are unheard of today.)

Americans have also elected more prosecutors at the local level who are unwilling for moral, practical, or budgetary reasons to pursue death sentences. That shift has exacerbated stark geographic divides in how Americans are sentenced to death and executed. DPIC reported that just 34 of the more than 4,000 counties, parishes, and boroughs in the United States produced half of the nation’s death sentences. “Two percent of U.S. counties accounted for 60.8 percent of all state death-row prisoners,” the organization noted, and “82.8 percent of U.S. counties did not have anyone on death row.”

All of these flaws—procedural and practical mishaps, growing public disapproval, the sheer randomness of geography, and more—might have prompted past generations of Supreme Court justices to reconsider the capital punishment system that they resuscitated in 1976. But the court has instead taken the opposite approach. In just this year, the court’s conservatives have signed off on death sentences for one Black prisoner whose jurors told the court that they opposed interracial relationships and another prisoner who was so mentally unstable that he plucked out and ate his own eye. With the justices unwilling to remedy the system’s flaws, Americans will have to do it themselves.