When Healthcare.gov crashed upon launching in 2013, Republican critics were quick to blame big government. Yet it wasn’t the government that built the service: More than 55 private subcontractors and consultancies led nearly every aspect of the site’s development and drove the cost of the project to $1.7 billion.

While the consulting industry makes headlines for corporate scandals, such firms have taken on an outsize role in the public sector too. Not only do they advise governments, but they are increasingly taking over core responsibilities of governance, work traditionally done by public agencies. In the process, they create conflicts of interest along with a lack of transparency, and hollow out the expertise of the very departments they’re enlisted to help.

In South Africa, McKinsey has been embroiled in a series of scandals involving state-owned utilities and freight companies. In the United Kingdom, the government paid Deloitte over a million pounds ($1.22 million) per day for work on its Covid “Test and Trace” program. And in Sweden, hundreds of doctors and nurses faced the possibility of layoffs after the government hired firms, including Boston Consulting Group, to lead the renovation of the country’s second-largest public hospital.

In their new book, The Big Con: How the Consulting Industry Weakens Our Businesses, Infantilizes Our Governments, and Warps Our Economies, scholars Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington of University College London lay bare a decades-long relationship between public and private actors that began with conservative governments but was entrenched by the center left. I recently spoke with the authors about the effects of government reliance on the consulting industry. We discussed how consultants cultivate a reputation for expertise, what skills they really offer, and how government can become less dependent on them. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Spencer Green: The business of consulting firms rests on their reputations as experts who can maximize the efficiency—and profits—of large companies. But your book is also about their role in government. What do you see as the problem with consulting in government?

Mariana Mazzucato: There’s a big problem with government that goes beyond consulting, but consulting has benefited from that problem, which is the slow decimation of public-sector capacity and capabilities. Government has found itself weak: weak to battle climate change; weak to battle, in the U.K., Brexit; definitely weak to battle Covid-19. So in the U.K., famously, we somehow thought it was a good idea to bring in Deloitte to do the test and trace system.

Now, this is where we can start talking about consulting. Consulting companies do all sorts of different things for government. When you are on the sidelines, like if you are helping maybe figure out what the best catering structure might be for government, that’s one thing. It’s different when you’re at the center “doing” what’s actually a core function of government—like Healthcare.gov, in the U.S., where the digital infrastructure for that program was essential.

When governments stop doing that, there’s all sorts of things that happen, but one is they stop learning by doing. The learning happens elsewhere. So you have this kind of ideology that has convinced the government that it’s kind of rubbish, so the government doesn’t actually invest in its own capabilities. But the self-fulfilling prophecy is that then the less you do, the less you learn, the more in quotes “infantilized” you are. The more you become addicted, and needing these consulting companies.

S.G.: There’s almost a chicken-and-egg paradox to all of this. To what extent were these firms stepping up to meet a demand, and to what extent were they responsible for establishing that demand in the first place?

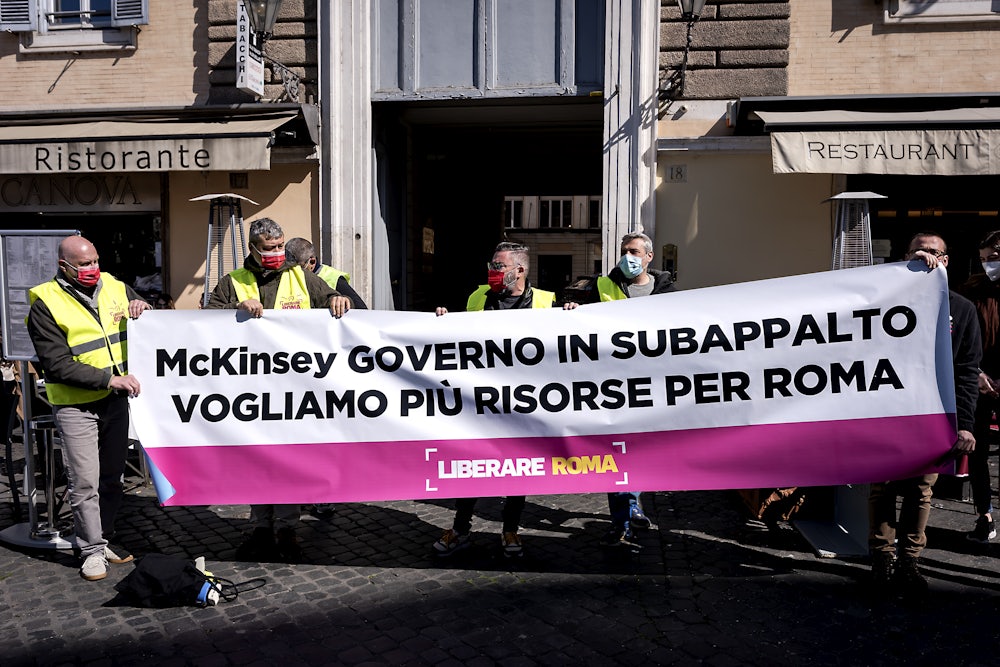

M.M.: We reflected quite a bit on this recently with some of our own experiences. In my case, I was one of several academics who [were] asked to be on the Covid-19 recovery team for Italy. There were at one point 13 McKinsey folks in the room. I was like, “What? Who opened the door to you guys?” And the guy running the commission who later actually became the minister for innovation in Italy, said, “Oh, but Mariana, come on, they’re just here for free—for free!”—taking notes, rendering the system much more efficient, right?

So there you have the fact that actually in many governments, you don’t have enough civil servants. You could just hire in some other students or McKinseyites to help. But McKinsey was there for free. And we call that lowballing: You’re there for free in the room, hearing very intense conversations. And then lo and behold, later, because you’re in the room, just seen as kind of helping a process, you obviously then get the contracts. So there’s a 2 trillion [euros; $2.15 trillion] recovery scheme of which something like 300 billion came to Italy, and McKinsey’s in the room thinking, how can this be spent? So there’s a lot of that lowballing: coming in for free in the beginning, precisely, almost to create the demand, and you as needed carry out the contracts that kind of come from that.

S.G.: Once the consultants are in, what are they adding that government couldn’t get from within?

M.M.: A lot of the trends in capitalism—whether it was the downsizing trend in the ’80s, the kind of shareholder value maximization in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and today the [environmental, social, and governance] targets—are trends that the consulting industry didn’t create but that they leech onto, often with no necessary expertise. What we mean when we talk about “consultology” is that often this kind of advice and consulting is literally just a cut-and-paste PowerPoint.

So these are the issues: (a) they’re surfing on the trends, (b) on top of weak capacity, at least on the government side, and (c) they’re charging fees, without necessarily creating value. If they were creating value, if they had something amazing to contribute that others don’t, then it would be a different story. But if you compare the actual knowledge and expertise they offer compared to the fees, these are actually almost rents in the system. It’s a question of value creation versus value extraction.

And it shouldn’t just be looked at in terms of numbers. In a lot of the scandals that have come out, including the climate one in Australia, where McKinsey got a 6 million Australian dollar ($4 million) contract, the issue was that the actual climate modeling was really poor.

Add to that the lack of transparency: If you’re also working for the fossil fuel industry on one side of the street and then advising the government on its climate strategy on the other, you actually have little incentive to make sure that you get rid of the fossil fuel industry. Because guess what? You’re also getting a lot of money from them.

S.G.: A lot of these scandals have been reported, and you would think it’d make the industry look pretty bad. Yet they maintain an air of expertise.

Rosie Collington: As Mariana mentioned, we have this whole chapter on “consultology,” which [is] the initiatives and things that consultancies do to help create the impression that they are creating value. And that can be both in terms of the practices on the ground, but it can also be in terms of, for example, their recruitment strategies. Other academics have written about how in the twentieth century, as the sectors were growing, it became increasingly important for consultancies to recruit from these top elite, Ivy League universities as a way of creating the impression that theirs was a legitimate profession in a way that, for example, wasn’t necessary in law, because that was a much more regulated profession—it had protected titles, for instance.

Consultancies have these quasi-academic research institutes that helped to create the impression that these are kind of hubs of knowledge, development. And again, it’s not as straightforward as saying these organizations never have knowledge; they never have any kind of expertise whatsoever. That would be kind of an insane thing for us to say. But on the ground, especially these junior graduate consultants who are going into these other industries or government agencies, they’re not the same people who are writing the report at McKinsey Global Institute.

So actually, the McKinsey Global Institute works very well to help create the impression that they are creating value on the ground, even if that’s not what the teams actually are able to do.

S.G.: To what extent can we step away from the dependency on consulting firms? What specifically do better models of governance look like?

M.M.: The Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose was set up to rethink the state, in order to strengthen its ability to co-govern the greatest challenges of our time. [Mazzucato is a founding director of the IIPP at University College London; Collington is a Ph.D. candidate there.] The institute is trying to do that in terms of helping governments on three levels. New research, new economic thinking—that’s our Ph.D. program, Rosie’s part of that. Second, maybe the biggest and most important thing we do is working with policymakers and learning on the ground. Like in Scotland, we helped set up a whole new public bank from scratch; we bring the learning from that to the theory. Lastly, we actually host a network of public organizations globally, called the Mission Oriented Innovation Network, that share their knowledge of what it looks like, feels like, literally the practice of stepping outside of this little narrow box where you’re always worried that you’re crowding out business. And we developed a framework that allows them to share their knowledge and experience.

R.C.: There are some governments who have explicitly recognized a problem with a reliance on consultancies for outsourcing. Unfortunately, not enough. But in Denmark, a new government came in in 2019 and said, Look, this doesn’t make any sense, it’s becoming very expensive, we can do most of this stuff better ourselves, and they did an internal audit of this reliance that they had. They decided to slash spending on consulting in half, which was a goal that they set kind of far ahead of time. One thing that they did was set up an internal public-sector consultancy, so that then in the short term, because they had been using them so much, there wasn’t this sudden deficit of capacity.

So there are governments who do recognize what we’ve identified in the book as a problem. And if you speak to civil servants, which we do every day, or if you speak even to people who work in consultancies, there are many people on the ground who recognize the problems with this sector and the problems of the relationship between government and business.

S.G.: The conversations around consultancies tend to use a “bad apple” framing. There will be a focus on one firm. Or on one specific problem across firms, like conflict of interest or bad incentives. What do you see when you look at the industry as a whole?

R.C.: This book would have been a very easy book to write if it was as simple as saying, “The consultants are the big baddies”—that everything that’s wrong with capitalism, all of these issues that Mariana has described, that’s the fault of the consultants. That’s not what the “Big Con” is. The “Big Con” is about the relationship between governments and consultancies, how one feeds off the other and has developed this kind of parasitic relationship that has the effect of hollowing out capacity internally or legitimating controversial decisions in business and government, such as restructuring.

M.M.: And of course, it’s not enough to complain. We make some concrete recommendations, precisely around how to build contracts, for example, that are much more transparent, how to make governments know who else is being advised by that same consultant—as was the case with Eskom and the South African Treasury Department or the fossil fuel companies that are being advised by the same consultant who is advising the government on its green strategy.

But also a new narrative is required. As Che Guevara said, “We need a new man,” or a new woman. You can’t just have better policy. We need new mindsets around collective value creation, understanding the state as being able to do much more than just act as a market shaper, at least in democratically elected societies, realizing it really needs to invest around that capacity. Without that, you’re always going to be addicted, literally almost, to the drug of consultants.