It was June 10, 1964, and Clair Engle was dying. The first-term California senator was a blunt and flamboyant liberal, but now he was confined to a wheelchair and had trouble with words. Nonetheless, on this day, his aides wheeled him out onto the floor of the U.S. Senate so that he could cast one of the most important votes in the chamber’s history—and Engle did so not with his voice, but with an unforgettable gesture.

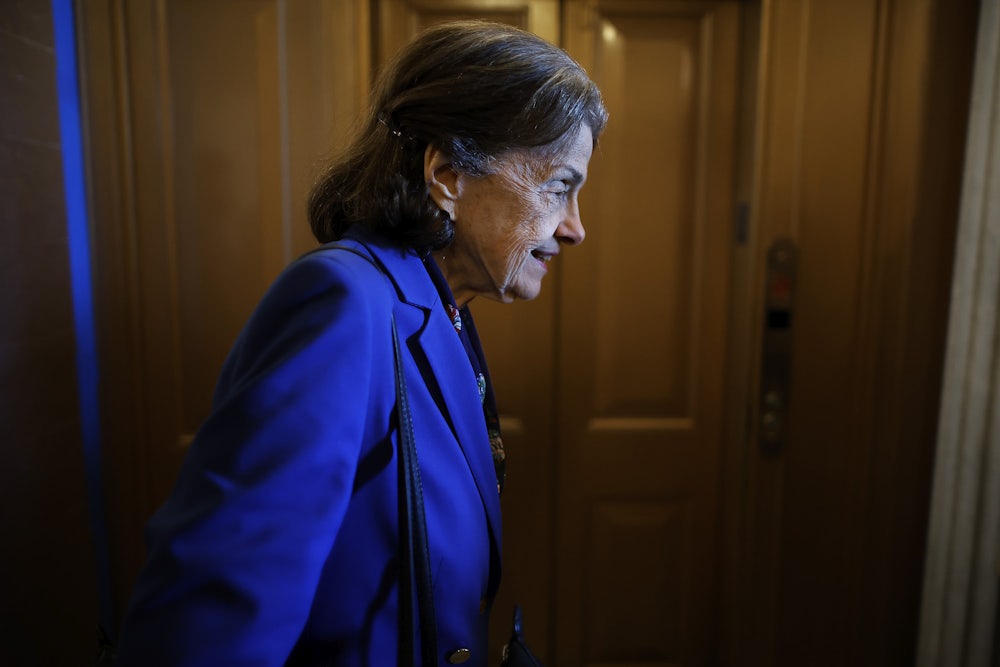

It’s a story that ought to guide the California senator who now holds his seat: the ailing Dianne Feinstein.

Engle had not appeared on the Senate floor since April 13. “At that time, he had struggled to his feet and tried to speak for a bill he wanted to introduce,” according to a New York Times report from Capitol Hill. “He had been unable to speak.” Such were the devastating aftereffects of the two operations that the 52-year-old Engle had undergone for a malignant brain tumor.

Two months later, Lyndon Johnson and Senate liberals desperately needed the vote of the homebound and dying Engle to break the Southern segregationist filibuster against the landmark Civil Rights Bill. Engle was rolled onto the Senate floor—“smiling slightly,” the Times reported—to vote for cloture, which shuts off debate and moves legislation to a vote. Once again, Engle tried to speak. He could not. So he raised his left arm and pointed to his eye. Translation: “Aye.”

Even though his “yes” vote was not needed nine days later for final passage of the Civil Right Bill, Engle was back on the Senate floor in his wheelchair to be a part of history. Six weeks later, he died in his sleep.

Feinstein’s situation is somewhat different. The 89-year-old has been at home in San Francisco since February, recovering from shingles. No one appears to have a clear sense of when Feinstein will return to the Senate, since her arrival has been delayed more often than Godot’s.

So Democrats wait with frustration. Without Feinstein in Washington, they lack a majority on the Judiciary Committee. Five would-be Joe Biden judges are stuck in limbo, with more in the pipeline, since the committee’s Democrats don’t have the votes to move these nominees to the Senate floor. And last week, Senate Republicans objected to a scheme to temporarily replace Feinstein on the committee with a healthy Democrat. As long as Republicans can filibuster such mid-session committee membership changes, the Democrats are stymied.

Of course, Senate Democrats should have seen this problem coming. More than a year ago, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a well-reported article in which Feinstein’s colleagues expressed concern that she was “mentally unfit to serve,” as the headline put it. Feinstein supposedly didn’t recognize longtime colleagues, often repeated herself, and could not follow policy discussions. The story and others like it prompted calls for Feinstein’s resignation, which she stubbornly resisted.

The real mistake, though, was made at the beginning of this year, when the Democrats decided whom to appoint to all the Senate committees. Sensitive to Feinstein’s feelings and the chamber’s traditions, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer allowed her to keep her seat on the Judiciary Committee, which she used to chair. This compassionate decision and the failure to anticipate that Feinstein might miss many votes has now made the Democrats vulnerable to the latest installment of McConnell’s hardball tactics.

It is tempting to believe that the problem would miraculously disappear if Feinstein belatedly resigned, because Democratic California Governor Gavin Newsom could then appoint a temporary successor. Left-wing California Congressman Ro Khanna has been particularly vocal in his calls for Feinstein to step aside.

There’s just one problem: The Democrats would need either unanimous consent or a filibuster-proof majority to appoint a senator to replace Feinstein on the Judiciary Committee in the middle of the term. Generally, during situations like this, the Senate operates under unanimous consent. But McConnell has defied Senate tradition before, especially with his refusal to even give Merrick Garland a hearing on his Supreme Court appointment in 2016. Jon Tester, Montana’s moderate Democratic senator, said recently that McConnell, who cares passionately about blocking liberal judges, would probably not relent even if Feinstein resigned. As Tester told Burgess Everett from Politico, “That’s what I’m hearing … it won’t make any difference.”

So are the Democrats really stuck, unable to confirm a single judge with even a whiff of controversy? Once again, McConnell—who had a six-week absence from the Senate himself after a fall and a concussion—is demonstrating that he cares more about thwarting Democrats’ judicial appointments than preserving the chamber’s comity and customs.

All of this brings us back to the stirring example of Clair Engle.

If there were any way for Feinstein to physically return to the Washington area—on a chartered medical plane if necessary—then she must do it. She could attend a few meetings of the Judiciary Committee, guided by aides and using a wheelchair, if needed. She doesn’t have to speak or follow the debate on the nominees. She just has to be able to point to her eye.

Yes, it would be a somber denouement for the pioneering senator. But sometimes in politics, as in life, there are issues more important than personal comfort and dignity. And if Feinstein manages to pull an Engle, she will end her storied career with a few glorious gestures that, by helping Biden to counter Trump’s right-wing judges with liberal nominees, could have repercussions for Americans’ civil rights for decades. It would be every bit as brave a goodbye as Engle’s was.