The Republican Party just can’t make up its mind about the $1.5 trillion budget deficit.

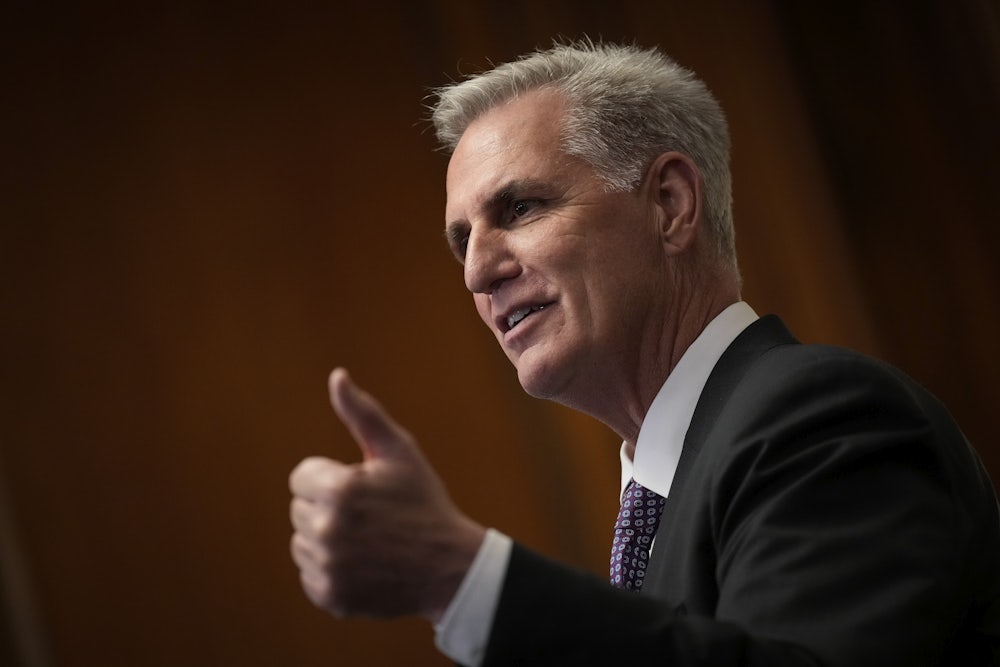

At the start of 2023, House Republicans refused to raise the debt ceiling unless the deficit came down. “We must move toward a balanced budget,” House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said in February. Eventually McCarthy settled for a bill that suspended the debt ceiling until 2025 and, according to the Congressional Budget Office, reduced the deficit by $1.5 trillion over 10 years.

But on June 13, the House Ways and Means Committee passed the Build It in America Act, 24–18, a tax cut that would increase the budget deficit by $157 billion over the next 10 years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. The measure is part of a package of three bills called the American Families and Jobs Act that together, according to the nonprofit Committee for a Responsible Budget, would (again, over 10 years) erase $1.1 trillion of the $1.5 trillion in savings from the deficit-ceiling bill.

This quantity of deficit reduction, you’ll recall, was so overwhelmingly necessary at the end of May that House Republicans were willing to risk default on the U.S. debt in order to achieve it. Yet two weeks later, their tax-writing committee pissed away nearly all of those savings in tax cuts. A logical conclusion would be that when House Republicans say they want to reduce the deficit, they don’t really mean it. What they mean is that they want to cut government spending so that they can cut taxes by a roughly equivalent amount. Much of these tax cuts would go to business. I say “would” because after this bill passes the House, the Senate will ignore it. Still, the hypocrisy is galling.

Perhaps you’re thinking: Wait. Didn’t President Donald Trump already slash corporate tax rates back in 2017, as part of a tax package that bled $1.7 trillion from the federal Treasury (so far)?

He did.

Didn’t that bill reduce corporate tax revenue from about 2 percent of gross domestic product to about 1 percent?

Yes.

Then what could possibly be left to cut?

Well, as I explained last month, you’ve got the pay-fors. “Pay-for” is Washingtonese for a measure in a tax-cut bill that offsets some portion of the revenue you’re going to lose. In the 2017 tax-cut bill, the pay-fors included three effective tax increases that the House GOP now wants to cancel. In my earlier piece I described each of these. Today I’d like to focus on just one of the three, “bonus depreciation.”

When a company—let’s call it Tim’s Warehouse—purchases an expensive piece of equipment—let’s say, a forklift—it’s permitted by the government to deduct part of the forklift’s cost from its taxes. Depreciation allows Tim’s Warehouse to allocate that expenditure over however many years the forklift is expected to remain useful, so that Tim’s Warehouse may, over multiple years, deduct the full cost. That encourages capital investment. Sometimes the government accelerates depreciation so that Tim’s Warehouse can, through lower taxes, recoup the full cost of the forklift faster. That encourages capital investment even more. Or so the theory goes.

Bonus depreciation was born in 2002, when President George W. Bush signed into law the Job Creation and Worker Assistance Act, which was passed to stimulate the economy after the 9/11 attacks. At the time, Tim’s Warehouse could typically deduct 14 percent of the cost of a new forklift in the first year, and declining percentages in succeeding years. The 2002 law added, in addition to that first year’s 14 percent, a “bonus” depreciation of 30 percent, increasing total depreciation in the first year to 44 percent, or nearly half the cost of the new forklift.

The 9/11 emergency ended, but the tax break intended to stimulate investment did not, which is how emergency tax breaks usually go. By 2017, bonus depreciation had risen to 50 percent. Still, capital investment had never fully recovered from the 2007–2009 recession—it still hasn’t—so the 2017 tax bill jacked up bonus depreciation so high that Tim’s Warehouse could deduct the full cost of its new forklift in the year of purchase.

Why is a bonus depreciation of 100 percent a pay-for? Because to lower the cost of the Trump tax bill, Congress made it temporary. It would remain 100 percent until 2022, then fall to 80 percent, then fall to 60 percent, and then fall, in 2026, to zero. In addition to saving revenue, at least on paper, the phaseout was expected to create a sense of urgency at Tim’s Warehouse. Better buy that forklift now, because you won’t get this good a deal forever! Now Congress is trying the opposite tack: Restore 100 percent depreciation in the first year, and keep it, well, forever.

When you’re a tax-cutting Republican member of Congress, one thing you’re well advised to avoid is any investigation of whether the tax breaks you legislated into existence had their desired effect on corporate behavior. That’s because they very seldom do. In the case of bonus depreciation, Lily Batchelor of New York University Law School examined in 2017 whether Tim’s Warehouse thought very much about it before it went ahead and bought its forklift. Her answer: not really.

What bonus depreciation has been really great for is lowering taxes for corporations that were in all likelihood going to make capital investments anyway. According to a recent report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, or ITEP, since passage of the Trump tax bill, bonus depreciation has thrown $67 billion in tax cuts at 25 highly profitable corporations, including Amazon, Disney, Google, and Facebook. Collectively, these 25 corporations paid an effective corporate tax rate of 12.2 percent (rather than the already-low 21 percent statutory rate created under the 2017 law, down from a previous top statutory rate of 35 percent). According to ITEP, fully 86 percent of that tax reduction was attributable to bonus depreciation.

Amazon, for instance, paid an effective corporate tax rate of 8.9 percent from 2018 through 2022, a phenomenally profitable period for the company. Amazon was able during these years to reduce its tax bill by $8.4 billion. Three-quarters of that $8.4 billion in tax savings, ITEP says, was attributable to bonus depreciation.

Disney, during the same period, paid an effective corporate tax rate of 7.7 percent, lowering its tax bill by $5.2 billion. Eighty-seven percent of that $5.2 billion was knocked off Disney’s tax bill by bonus depreciation. More examples are here.

Republican politicians like Senator Marco Rubio keep saying they want to check corporate power, but don’t hold your breath waiting for them to say don’t revive bonus depreciation (Rubio has long been a strong advocate for it), much less let’s raise the statutory corporate tax rate back up to 35 percent. Legislation disallowing corporate deductions for employee abortions and gender reassignment are more his speed.

Ron DeSantis may scream bloody murder about Disney practicing tolerance with regard to sexual orientation and gender identity. But you will never hear him say that his primary rival Donald Trump made a terrible mistake when he slashed taxes for Disney and every other giant corporation in America, not to mention the top income tax rate on wealthy individuals. And the next time you hear any Republican complain about the budget deficit, ask that Republican why his or her party has been so unsuccessful at lowering it. The answer, of course, is that they hate taxes much, much more than they love budget solvency.