“Surprise,” Fortune said in March. “The pandemic significantly shrank America’s wage inequality, and the trend may continue.” The Wall Street Journal put it more cautiously: “Wage Inequality May Be Starting To Reverse.” Time was more sweeping (“Income Inequality Hasn’t Risen In A Decade”), and Axios more exuberant still (“Global Inequality at Lowest Point in 150 Years”).

Forty-odd years ago, income inequality, which prior to 1979 had either shrunk or stayed constant since around the time of the 1929 crash, started growing. It’s been growing ever since. That hasn’t stopped. So let’s don’t throw any ticker-tape parades just yet.

What these headlines mostly refer to are a couple of economic studies that provide some encouraging news regarding low-wage work. One of these, published in March by MIT economist David Autor, University of Massachusetts economist Arindrajit Dube, and Annie McGrew, a graduate student in economics at UMass, found that the Covid labor shortage, which is already starting to abate, reversed one-quarter of four decades’ growth in income inequality between two specific groups: workers situated in the bottom 10 percent of the income distribution, and workers in the top 10 percent of the income distribution. The poor got richer and the rich—or anyway, the haute bourgeoisie—slowed its gains.

The other study, published in October by MIT sociologist Nathan Wilmers and Clem Aeppli, a graduate student in sociology at Harvard, has gotten less attention, but it’s probably more important. This study concentrated not on the post-Covid period, which is screwy in all sorts of ways that are now receding, but on the past decade. Wilmers and Aeppli found that between 2012 and 2022, the wage gap between the bottom 10 percent and the median either leveled off or declined. State-level minimum wage increases helped, but only a little. The main cause appears to be that declining birth rates reduced the quantity of low-wage workers well before Covid’s Great Resignation (which is now pretty much over). The poor got richer and the middle class stagnated.

That life may be getting better for the bottom 10 percent is very good news. It’s good news, too, that this specific improvement is attributable to wage growth and not more generous government benefits (though more generous government benefits are always welcome). It means that, even before Covid, poor people were acquiring greater market power—so much so that in 2012 the share of labor income going to the top half of the income distribution stopped growing, and even began to drop. Hallelujah.

But when experts talk about the shift toward growing income inequality starting around 1979, they aren’t talking about the gap between the bottom and the middle, which grew in the 1980s before leveling off in the 1990s. They aren’t even talking about the gap between the top half and the bottom half, because those categories are too broad. They’re talking about the gap between the middle and the top, which has never stopped growing.

As I’ve explained many times (I published a book on income inequality in 2012), it was lousy to be poor in 1979, and it’s lousy to be poor in 2023. It’s less lousy now, thanks to more generous government benefits and, we now learn, rising wages, and thank goodness for that. But it’s still pretty lousy.

It was not lousy, in 1979, to be middle class.

Your job was often more dangerous than it would be today, but the pay was more likely sufficient to feed, clothe, and shelter your family inside a stable community; to send your kids to college; to support yourself and your wife in retirement. Entry to the middle class was mostly barred for African Americans, and there was plenty else wrong with that now-vanished world. But economically, the middle thrived. Today it does not. And as the economic distinction between the median and the bottom tenth gets blurrier, the middle does not cry hallelujah. The sensible middle asks angrily why its wages have stagnated over four decades, and the subgroup that Hillary Clinton accurately (if unwisely) termed “deplorables” turns to white nationalism, xenophobia, incipient fascism, and the various other pathologies on offer from the MAGA right.

The Berkeley economists Emmanuel Saez, Gabriel Zucman, and Thomas Blanchet last year created a fantastically useful tool called Realtime Inequality that allows you to track income growth for various slices of the income distribution from 1976 right up through March 2023. What does it show about the income gap between the middle and the top? That it grew over the past decade, just as it did over previous decades. The growth was less substantial after taxes were factored in, but income inequality still grew. There was a single, brief moment of convergence during the two-month freak Covid recession of February-April 2020, which was an economic calamity for everybody. Otherwise, income growth diverged.

The divergence was especially stark between August 2020 and around January 2022. After that, income growth for the top 10 percent and the top one percent flattened out, as stock prices tumbled. Even so, between August 2020 and March 2023, income growth for the middle 40 percent—a rough proxy for the middle class—was 3 percent, compared to 14 percent for the top 10 percent and 24 percent for the top 1 percent. Inequality growth between incomes at the middle and incomes at the top is alive and well, thank you very much, and the divergence becomes more dramatic as you rise higher in the income distribution. The rich get richer, and the middle class gets bupkis.

When people talk about the growing gap between the middle and the top, they’re really talking about two phenomena. One of these is the gap between the working class and the professional class. This gap is driven largely by educational attainment, and its growth has slowed in recent years with a leveling-off of the “college premium,” i.e., the financial advantage gained from acquiring a college degree. It’s ironic that the working class/professional class divergence is the one that drives our politics even as this divergence diminishes (though it remains substantial; you should still want your kids to go to college). This seems to be a case of familiarity breeding contempt. The average working-class person doesn’t know any billionaires, but they encounter doctors and lawyers and teachers on a daily basis, and they experience enough of what feels like condescension to resent them. My own view is that they would resent the professional class less if Bidenomics didn’t exempt much of this group from tax hikes through President Joe Biden’s reckless pledge not to raise taxes on families making less than $400,000.

The other inequality phenomenon separating the middle from the top is the one familiar from the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011: growing income share for the top one percent at the expense of the bottom 99 percent. This form of inequality is familiar enough to register in opinion polls, which consistently favor raising taxes on the rich, but not familiar enough to prompt political action. Even congressional Democrats have resisted President Joe Biden’s attempts to raise taxes on the super-rich.

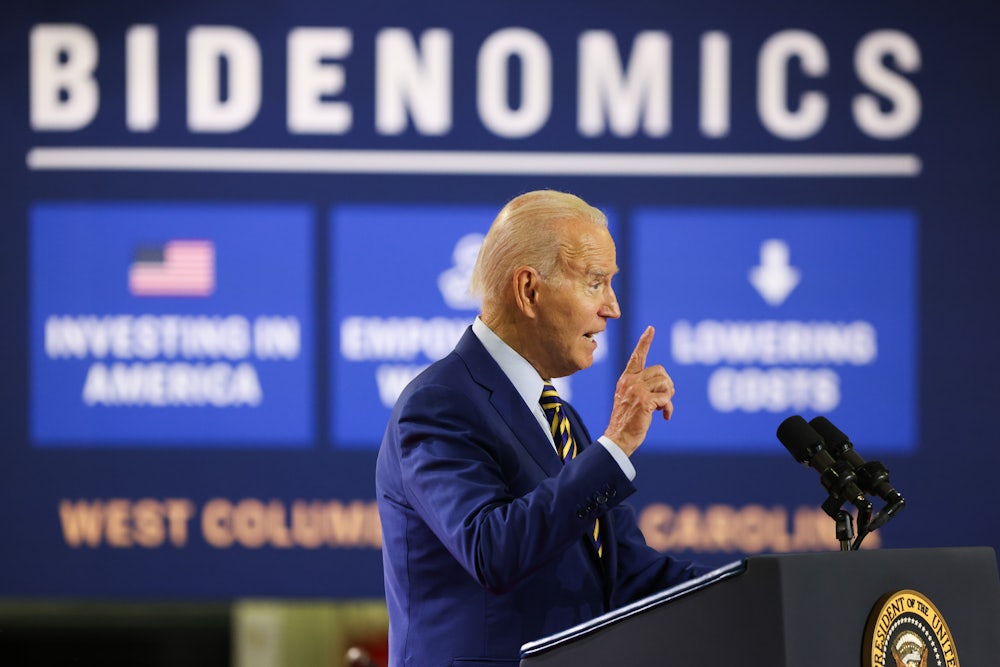

Bidenomics is, in general, succeeding in its middle-out approach, making the economy work better for everyone by keeping unemployment low, expanding gross domestic product, and, according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, creating 209,000 jobs in June at a time when the Federal Reserve can plausibly be accused of trying to create a recession to curb inflation. But Bidenomics isn’t reducing income inequality, partly because of what Congress won’t allow it to do and partly because of what Biden won’t yet allow himself to propose.

The greatest blow against inequality growth would be—and I know I’m a broken record on this point—passage of the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, which cleared the Senate HELP Committee June 21 on a party-line vote, 11–10. This went unreported everywhere but People’s World, the Marxist online daily that succeeded the Daily Worker. Yes, the bill is unlikely to advance in the Republican-controlled House. But the mainstream press didn’t apply that same logic to the Republican tax bill that cleared the House Ways and Means Committee one week earlier and received extensive coverage. The PRO Act would make it easier to join labor unions by increasing penalties for labor violations, eliminating state bans on unions charging fees to nonmembers who benefit from collective bargaining, prohibiting management from forcing workers to attend captive-audience anti-union propaganda sessions, and other commonsense measures. It is long overdue, and economic progress for the middle class is likely impossible without its passage, which the Biden administration strongly supports.

Where Bidenomics dares not go is deep into financial re-regulation, which is the only way to put a choke chain on the one percent. Biden talked a good game during the 2020 election, and he made a very strong appointment in Gary Gensler, chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission. But apart from a few isolated measures like an excise tax on stock buybacks that Biden wants to quadruple to 4 percent, Biden hasn’t pushed very hard in this area. He’s proposed raising the corporate tax to 28 percent, up from the 21 percent where President Donald Trump’s tax bill set it, but not all the way up to the top rate of 35 percent that existed before 2017. Biden has moved aggressively on antitrust, but he hasn’t proposed any sweeping follow-ups to 2010’s Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, which was supposed to mark the beginning rather than the end to financial re-regulation. Part of the problem may be that Wall Street has taken a shine to Bidenomics, with Wall Street figures like former hedge fund investor Mark Gallogly hosting fundraisers for him.

What’s needed is a stiffer dose of Bidenomics. After the collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, Senator Elizabeth Warren, Democrat of Massachusetts, and Representative Katie Porter, Democrat of California, introduced a bill to repeal an ill-considered 2018 Dodd-Frank rollback that reduced regulation of midsize banks. Biden did not endorse this. The Biden administration has proposed greater regulatory supervision of nonbank financial institutions, but no comprehensive legislation to bring this sector to heel. It has laudably proposed strengthening the inheritance tax, but it’s done nothing to check the epidemic at the state level of locking up family fortunes in multigenerational trusts. Biden has not moved toward making the financial sector the same respectable-but-boring place it was before the Depression-era restraints placed on it were lifted starting in the 1970s.

Until Biden and the Democrats step up to these challenges, income inequality will continue to grow, under Republican and Democratic presidents alike. It will grow more under Republicans, as it has in the past. But this blight on America’s economy and its politics can’t be removed within the framework of what’s politically salable today. We need a more imaginative and more daring version of Bidenomics. You’ve done a pretty good job so far, Mr. President, and I know that politics is the art of the possible. But the cause of greater equality requires you to expand what’s possible as only a powerful chief executive can.