The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned part of the FDA’s approval for the most commonly used abortion drug in the nation on Wednesday, a move that could significantly affect Americans’ ability to obtain the procedure in much of the country. The three-judge panel’s ruling would sharply limit the availability of mifepristone, including in states where abortion is now otherwise illegal in most circumstances after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

“In loosening mifepristone’s safety restrictions, FDA failed to address several important concerns about whether the drug would be safe for the women who use it,” Judge Jennifer Walker Elrod wrote. The panel unanimously struck down rule changes in 2016 that made mifepristone more widely available, as well as a 2021 decision that allowed the drug to be dispensed by mail.

Wednesday’s ruling does not affect the current availability of mifepristone, which has important medical applications beyond merely abortions. The Supreme Court issued an order in April that the lower court’s rulings on the drug will not take effect until the justices can review them, thereby preserving the status quo. But the decision does set up what would be the first major post-Dobbs ruling on abortion access before the Supreme Court—and it does so on starkly anti-abortion grounds.

The case, FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, involves a challenge to FDA regulatory decisions about mifepristone. It was brought by a group of anti-abortion medical practitioners who disagree with the agency’s guidelines for administering the drug. They questioned the drug’s safety and utility, raised ethical concerns about prescribing it, and said that the FDA had improperly approved mifepristone in the first place in 2000. The FDA, for its part, insisted that its approvals were lawful and that the plaintiffs had no scientific or legal grounds to challenge them.

Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk ruled in the anti-abortion doctors’ favor on nearly all grounds earlier this year, imperiling access to the drug nationwide. His ruling, though remarkable, was also unsurprising. Before former President Donald Trump nominated him to the district court seat in 2017, Kacsmaryk had worked for a conservative Christian legal organization that sought to overturn Roe and had publicly condemned it himself. The anti-abortion doctors who brought the case were able to practically guarantee that he heard the case, thanks to the way federal district courts in Texas draw their internal jurisdictions. It turns out that it’s a lot easier to win a lawsuit when you can pick the judge who hears it.

The Fifth Circuit panel, which also consisted of three Republican appointees, did not go as far as Kacsmaryk did. Two of the three judges concluded that the plaintiffs did not have standing to challenge the FDA’s 2000 approval of mifepristone because federal law generally requires those challenges to be filed within six years of the agency’s action. That clock started when the FDA denied a citizen petition to re-review the drug in 2002, and it expired roughly fifteen years ago. As a result, the panel held that the most that the plaintiffs could do is turn the regulatory clock back to 2016, when the FDA last amended its guidelines for mifepristone.

On those grounds, however, the plaintiffs prevailed. Elrod, writing for the panel, concluded that the changes in 2016 were invalid because the agency had not conducted sufficiently precise studies on its possible effects for patients. “The cumulative effect of the 2016 Amendments is unquestionably an important aspect of the problem; indeed, that was the whole point of FDA’s action,” she wrote. “Because FDA failed to seek data on the cumulative effect, and failed to explain why it did not, its decision to approve the amendments was likely arbitrary and capricious.”

“Arbitrary and capricious” is a normal legal standard for assessing federal agency rules. But it is fairly unusual for the courts to use it to second-guess the FDA’s drug-approval process. Kacsmaryk’s original ruling was the first time that a federal court had ever overruled an FDA decision about whether a drug was safe for the American market. While the Fifth Circuit did not invalidate mifepristone’s original approval in 2000, as Kacsmaryk tried to do, it still put itself in a position where judges were telling scientists and medical professionals how to properly weigh drug safety and efficacy.

Judge James Ho, a member of the panel, argued forcefully for his power to do that in a partially concurring opinion. “Scientists have contributed an enormous amount to improving our lives,” he wrote. “But scientists are human beings just like the rest of us. They’re not perfect. None of us are. We all make mistakes. And the FDA has made plenty.” He then cited examples of past misjudgments by the agency, leaning heavily on an erroneous drug approval in the 1940s and claiming that it bore some responsibility for the opioid crisis. In his telling, judicial intervention in the FDA drug-approval process is not a mistake, but a positive good.

Beyond that, Ho would have given the anti-abortion doctors a victory across the board. He wrote that the FDA’s drug approval for mifepristone could be reviewed because of subsequent changes, and that he would invalidate it because, in his view, pregnancy does not count as an “illness” under the portion of the statute cited by the FDA. (This might be a surprise to the countless women who have experienced difficult or dangerous pregnancies.) He would also have invalidated the mail-order changes in 2021 under the Comstock Act, a largely unenforced federal law that criminalizes the distribution of abortion drugs in the mail.

Most striking of all is Ho’s understanding of, well, legal standing. To bring a lawsuit, a plaintiff generally needs to show that they have an injury that a court can remedy. Without that, they have no justification for bringing the lawsuit at all. The panel allowed the anti-abortion doctors to proceed with their lawsuit on associational standing and conscience grounds. Ho did not disagree with that conclusion, but he put forth an even broader theory for why anti-abortion doctors could file these types of lawsuits: what he described as the “aesthetic injury” suffered by doctors who witness an abortion.

“Unborn babies are a source of profound joy for those who view them,” Ho wrote. “Expectant parents eagerly share ultrasound photos with loved ones. Friends and family cheer at the sight of an unborn child. Doctors delight in working with their unborn patients—and experience an aesthetic injury when they are aborted.” That “aesthetic injury,” he concluded, would allow doctors to bring lawsuits that could limit their patients’ access to abortion drugs. It is not clear where the limits of such an “injury,” if any, would be.

To support this claim, Ho cited environmental law cases where environmental groups asserted harms based on damage to natural spaces or the wildlife within them. “It’s well established that, if a plaintiff has ‘concrete plans’ to visit an animal’s habitat and view that animal, that plaintiff suffers aesthetic injury when an agency has approved a project that threatens the animal,” he wrote. He cited no precedents where a court had ever applied that approach to human beings directly interacting with one another. It also seemed to be a radical departure from Ho’s own stated belief in originalism and textualism.

Expanding that concept beyond the environmental realm would upend traditional standing principles, to say the least. Could I sue the Philadelphia Eagles for injuring Brock Purdy in the NFC Championship game in February? I would happily swear to any court in the republic that my “aesthetic injury” as a San Francisco 49ers fan from that game is immense and ongoing. More serious hypotheticals show the tenuousness of this approach. Could emergency-room doctors bring aesthetic-injury lawsuits against gun manufacturers? Could doctors in states without rape and incest exceptions for their abortion bans invoke an aesthetic injury after treating survivors of sexual assault?

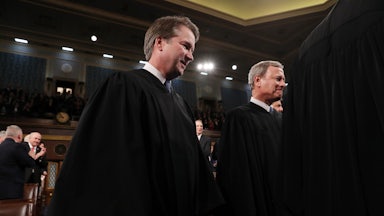

The Supreme Court’s approach to standing in recent years has been somewhat strained, but it is hard to imagine that even the court’s conservative majority would be willing to go as far as Ho wants. It is also unclear whether they will even go as far as the rest of the panel did on Wednesday if they choose to review the ruling. Chief Justice John Roberts opposed the court’s decision to overturn Roe outright in Dobbs last year and Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a separate concurring opinion where he strongly suggested that he would not vote to uphold certain restrictions on it.

Beyond the abortion context, the justices may also be reluctant to meddle too much in the FDA drug-approval process, a point vociferously raised by drug companies and medical associations after Kacsmaryk’s ruling in April. Justice Samuel Alito wrote last year that by overturning Roe, the court was returning decisions over abortion to the American people and their elected representatives, not to unelected judges. Wednesday’s mifepristone ruling, if appealed, will give the court a chance to show they were serious about that.