House Republicans are pressing forward with a plan to cut billions of dollars from a critical nutrition program by forcing states to shoulder more of the cost, threatening benefits for roughly 42 million low-income Americans in red and blue states alike.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, known as SNAP, has traditionally been fully funded by the federal government and administered by states. But this week, the House Agriculture Committee approved along party lines a measure that would slash more than $290 billion from SNAP, formerly known as food stamps. These cuts would be achieved in part by pushing a portion of benefit costs onto states, as well as requiring individual states to shoulder more of the administrative expenses.

Haley Kottler, campaign director at Kansas Appleseed, an anti-hunger advocacy organization, described the potential changes as “the most outlandish policy that I’ve seen on SNAP, maybe ever.” According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, requiring Kansas to pay for 25 percent of SNAP benefits would cost more than $100 million over six years.

“If these go through, it absolutely will wreak havoc on the program overall,” said Kottler. “For one, we don’t have that in our state budget right now, and two, lawmakers in Kansas do not have the political will to put any more money forth for SNAP.”

If the bill passes both chambers of Congress, beginning in 2028, states would be forced to pay between 5 percent and 25 percent of SNAP benefits based on payment error rates. In 2023, more than half of all states had an error rate of higher than 10 percent, meaning that they would shoulder a quarter of the cost of SNAP. Kansas, for example, had an error rate of more than 12 percent in 2023.

Kottler said that she was disheartened but “not surprised” by the efforts to cut SNAP, as they echoed recent bills in her state’s legislature to expand work requirements and shave program costs. She was skeptical of House Republican assertions that states would understand the shift in cost and would be able to pick up the slack.

“I’m a fifth-generation Kansan, and I’ve been working with our state legislature for six years now, and I’ve never heard them being interested in something like that,” said Kottler.

Elaine Waxman, senior fellow in the Tax and Income Supports Division at the Urban Institute, noted that SNAP payment error rates increased amid the upheaval of the coronavirus pandemic and that the state offices administering the program remain understaffed and underfunded. Historically, states and the federal government have split the cost of administering SNAP evenly. Under this bill, states would now be responsible for 75 percent of administrative costs, which would make it even more difficult for them to balance supervising the program and providing benefits themselves. The bill would also lower a “tolerance level” for SNAP error payments from $37 to $0, which would likely increase error rates across the board.

“You’re [between] a rock and a hard place in that, OK, you have a higher error rate—in order to get your error rate down, or to implement other things that will reduce your costs, you need more administrative investment, probably. But where will that be coming from?” she said. “You had an atypical situation the last few years, and so you’re predicating the program on an atypical situation, but without diagnosing why things are the way they are, and what would be required to make them better.”

As nearly every state has some form of balanced budget requirement, they may not have the leeway to expend greater funds on providing SNAP benefits. “What states cannot do, that the federal government can, is they cannot infinitely borrow to run an entitlement program,” said Lauren Bauer, associate director of the Hamilton Project. “Pushing things off onto states who do not have the capacities that the federal government does is a way to push responsibility onto people who don’t have every tool that they would need to to prevent the shrinking of these programs.”

States would have limited options for finding the funds to cover increased SNAP costs that Republicans are proposing. One potential route states might take would be eliminating “broad-based categorical eligibility,” a policy that allows households to participate in the program if they qualify for certain other benefits. Eliminating this policy would increase bureaucratic red tape for families who would suddenly be dealing with a more complicated application process and potentially result in people losing their benefits. This, in turn, would affect access to other programs—for example, children would no longer be automatically enrolled in free school meals or immediately qualify for early childhood nutrition programs.

“Should this cost shift go through, states would have to pull back on this SNAP expansion, and leave people who need the program without a recourse,” said Salaam Bhatti, SNAP director at the Food Research and Action Center. “It’s not just a ripple effect that these proposals have. It’s a shock wave.”

SNAP can be considered an “automatic stabilizer” during times of economic hardship because it allows for the rapid enrollment of people who are newly eligible due to job loss or other financial struggles. During the Great Recession and the coronavirus pandemic—which saw significant expansions in program benefits—SNAP was a key resource for Americans suddenly floundering in an unstable economic environment. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has estimated that every $1 spent on SNAP during a recession generates $1.50 in economic returns.

“Let’s say that you’re in a place where a lot of people have lost their jobs because a recession is starting, but more people go onto SNAP to help buffer that income decline. And so what does that mean? Well, they can still go to the grocery store and buy food. So what does that mean? Well, it means that the grocery store doesn’t need to lay off one of their checkout people, or one of their shelf stockers,” said Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, an economist at Northwestern University who studies policies addressing child poverty. “There’s a multiplier effect.”

With economists warning of a potential recession on the horizon—with uncertainty surrounding tariff policy simultaneously heightening and lessening worries of an economic downturn—cuts to SNAP would mean losing that automatic stabilization. A recent report co-authored by Waxman estimated that, should the U.S. enter a recession, states subject to a 10 percent cost share would need to spend an additional $980 million in the first year of the economic downturn to cover increased benefit costs. The report also found that if states did not increase spending, but instead reduced benefit amounts, all SNAP participants would face an average reduction in benefits by $327. Given that these changes would be implemented beginning in fiscal year 2028—crucially, after the 2026 midterm elections that will be a referendum on Republican guardianship of Congress—it’s uncertain where the economy will be at that point.

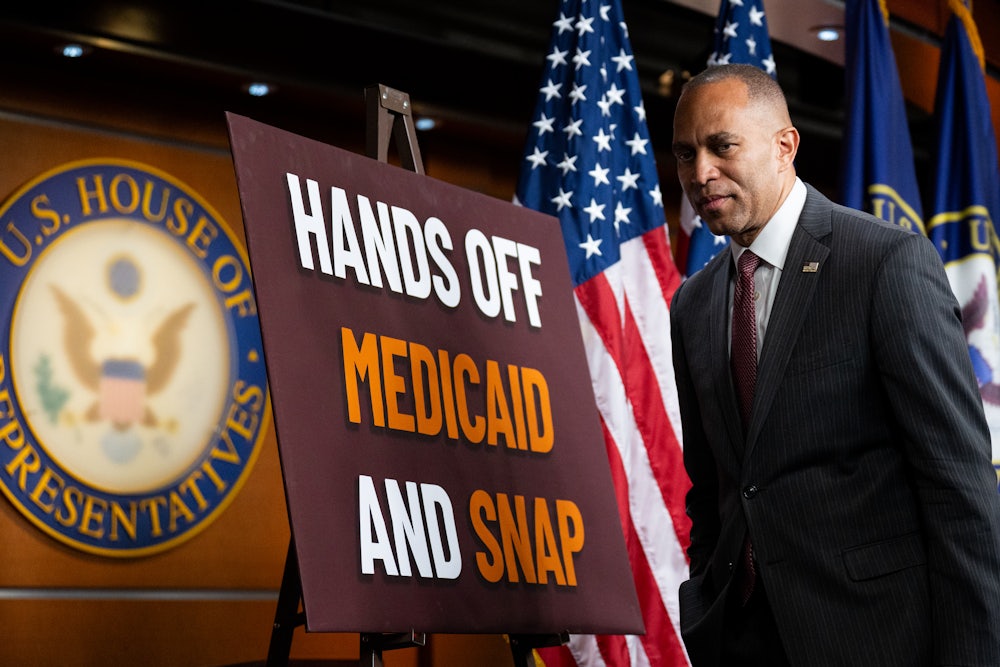

The potential changes to SNAP are not happening in a vacuum—the cuts are part of a massive package to slash federal spending and extend tax breaks that Republicans are currently trying to muscle through both chambers of Congress, through an arcane process known as “budget reconciliation.” The bill also includes cuts to Medicaid that could result in millions of low-income people losing their coverage at the same time that they see changes to SNAP benefits, even as losses in SNAP benefits are associated with poorer health outcomes.

“Ironically, if you’re cutting SNAP, you may push that pressure over onto the Medicaid program … at the same time that you’re looking at cutting Medicaid,” said Waxman.

While shifting more costs onto states would comprise roughly half of the $290 billion in proposed cuts to SNAP, tightening work requirements would slash an additional $92 billion in spending. Currently, able-bodied adults without children under age 54 can receive SNAP benefits for only three months over a three-year period unless they are able to prove that they are fulfilling a 20-hour-per-week work requirement or are disabled. The Republican plan would lift that cap to able-bodied adults without dependents up to age 64. It would also tighten work requirements for parents; instead of allowing parents with children under age 18 to be exempt from work requirements, those exemptions would only apply to parents with children under age 7. Research by Bauer has shown that SNAP work requirements do not meaningfully increase employment, and lead to a decrease in program participation.

It’s uncertain whether the cuts to SNAP will pass as is, given that the reconciliation bill still needs to pass the House, and some senators have appeared skeptical about changes to federal benefit programs. Efforts to address some issues in the reconciliation bill that would normally be part of the farm bill—the massive legislation that oversees nutrition, agriculture, and conservation policy—may also run afoul of Senate rules.

Still, even with changes to the bill on the horizon, the proposal to slash SNAP spending indicates where Republican priorities lie. Bauer argued that the intention of the cuts to SNAP did not fulfill the program’s purpose of assisting low-income Americans but that instead they were merely concerned with cutting the federal deficit.

“This program right now is about reducing human suffering, getting people back on their feet, improving nutrition and food security outcomes, preventing hunger, stimulating local economies, helping rural economies, helping rural grocery stores, helping all grocery stores,” said Bauer. “All of the proposals that are in this bill are cost-cutting. That’s why they’re there.”