As Robert F. Kennedy Jr. works to dismantle the long-standing infrastructure for providing vaccine guidance, Democratic governors are working to build their own shadow public health systems, in order to both prepare for disease outbreaks and counter their risks in a climate of mounting uncertainty. These interstate alliances may represent the future of public health in the United States, where the federal government is no longer trusted as a centralized source of information, and a state’s response to disease threats depends on its partisan makeup. But these are untested models, with no guarantee of success.

The federal government has traditionally been the trusted source for providing centralized information and guidelines on vaccines, which states would then use when formulating their own health policies. But that trust is no longer a given.

“It just shows that we’re living in a very partisan time for public health, and for views about vaccines and vaccine access,” said Jennifer Kates, senior vice president and director of the Global and Public Health Policy Program at KFF, an independent health policy research, polling, and news organization.

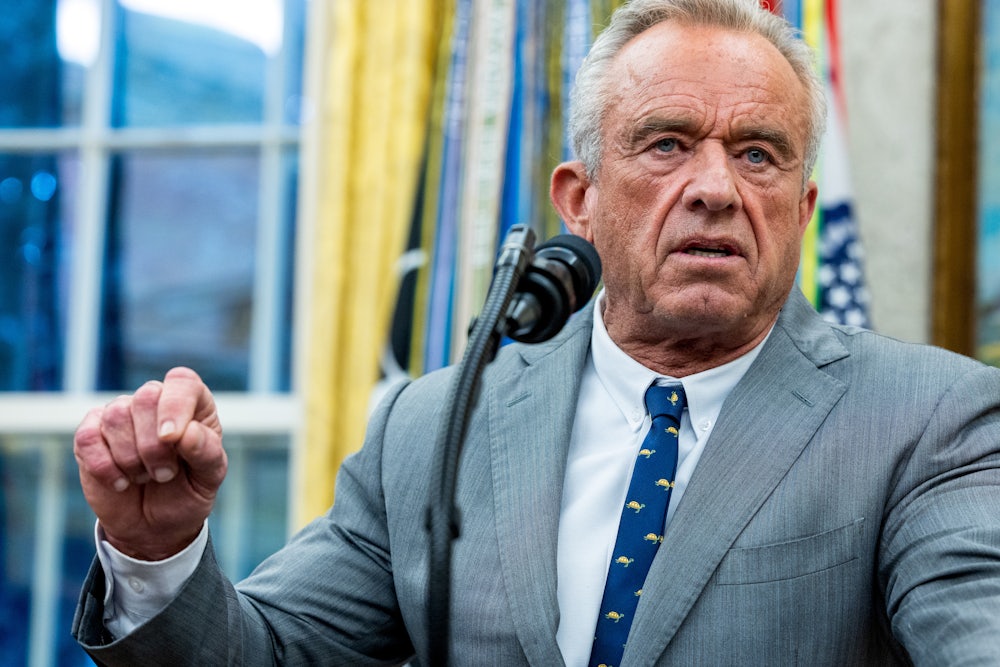

In the months since Kennedy became secretary of Health and Human Services, his vaccine skepticism has dramatically reshaped the agency. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been hollowed out under Kennedy’s leadership, with mass layoffs that began in January, as well as dramatic staff shakeups, such as the ouster of its director over the summer. In recent weeks, chaos has consumed the CDC with the firing and rehiring of hundreds of employees amid the current government shutdown. Kennedy has also completely reshaped the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the panel which helps determine federal vaccine policy, dismissing its existing members and handpicking their replacements over the summer. This committee recommended new restrictions on combination vaccines given to children last month.

In response, several Democratic governors have joined forces to formulate their own alternative public health response. Last month, a cluster of states on the west coast announced that they were forming an alliance to develop their own vaccine guidelines counter to what is provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten northeastern states soon followed with their own coalition shortly thereafter. This week, Democratic governors across 15 states—cumulatively representing around 115 million people—announced the Governors Public Health Alliance to collaborate on research and disease prevention efforts. Although the new consortium bills itself as nonpartisan, no Republican-led states have joined the effort.

It is not new for governors to consult with each other on public health issues that cross state lines, said Jason Schwartz, associate professor at the Yale School of Public Health. But these alliances are an effort not merely to supplement the CDC on outbreak response in particular, but even to provide a new point of reference that supplants federal guidance.

“This moment probably called for elevating, expanding, increasing those collaborations in ways that [states] could share best practices, could join forces—could be ready, more importantly, to respond more quickly if the weakening of our federal public health apparatus increases in the way that it has,” said Schwartz, who also serves on an advisory committee to the Connecticut State Department of Public Health.

Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, noted that some private organizations also issue their own guidelines, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics. But where these recommendations have been “harmonized with CDC for decades,” said Adalja, “you can no longer do what’s right for the patient in front of you and follow the CDC guidance.” For the average primary care practitioner, this will result in a confusion about which guidelines to follow, he continued.

“It’s one thing if the clinician is an infectious disease doctor who can actually interpret the data and think through the merits … but that’s not the case for most people who are vaccinating,” said Adalja. “It makes it harder for them to sift through the guidance of, ‘This state says this, this neighboring state says this, the American Academy of Pediatrics says this—which of these is the one that applies to my patient in front of me?’”

The guidelines that the state coalitions may devise aren’t binding; as with CDC guidance, it would be up to individual states how they wished to interpret these recommendations for implementing their own policies. Rather than basing these policies on information from the federal government, states will be pooling it themselves. But there are certain things state coalitions cannot do, particularly with regard to vaccine affordability. Most private insurance, as well as Medicaid and some Medicare plans, are required to cover vaccines recommended by ACIP and the CDC for free. So, for example, with the limits on the Covid-19 vaccine announced earlier this year, most payers are no longer required to offer that service free of cost.

“If a vaccine were no longer to be endorsed by the federal officials, it’s nice if the state groups were to recommend it, but that wouldn’t be sufficient” to ensure cost-free coverage, said Schwartz. These coalitions have floated joining forces to directly strike deals with vaccine manufacturers and purchase them in bulk, so they can then offer them to residents free of cost. But for the most part, he predicted, these alliances would be more about open communication and mutual preparedness than acting as a shadow CDC.

“We’ve not heard about large resources being poured into this financially, or dedicated large independent staffs, but rather some kind of a convening secretariat,” Schwartz said. “It feels much more like [something] closer to the kinds of professional organizations that already exist around among state epidemiologists or state health commissioners, but ones that just provide a more shared environment in which to support each other.”

Regardless of what these alliances can actually accomplish, the larger issue may be what these coalitions represent on a symbolic level: an increasingly fragmented public health system, which will overall make it more difficult to respond to crises in a unified manner.

The long-term consequence of increased partisanship is that public health in the United States is “stuck,” Kates said, because political polarization has become the determining factor for responding to a crisis.

“When decisions about public health are made based on politics, and not based on data and science, that can hinder public health for everybody,” she said. “When you think about infectious diseases, in particular vaccine-preventable diseases … those diseases do not really care if you live in a red or blue state.”

Kates also noted that states are already beginning to implement different policies on issues such as fluoride in drinking water, and cited issues like sexually transmitted infections and HIV response as another area where red states could potentially follow administration guidance while blue states take different tacks.

With the CDC under Kennedy’s leadership more likely to take steps to limit access to vaccines, experts worry that the balkanization of responses to crises will only worsen, regardless of how states respond. But Adalja argued that if states repudiate the advice from the CDC, it will ultimately be better for the nation’s health long-term.

“I don’t want anybody to listen to anything that RFK Jr. says,” said Adalja. “The more people that ignore the CDC, the more people that ignore any agency that RFK Jr. controls, the better off that person will be.”