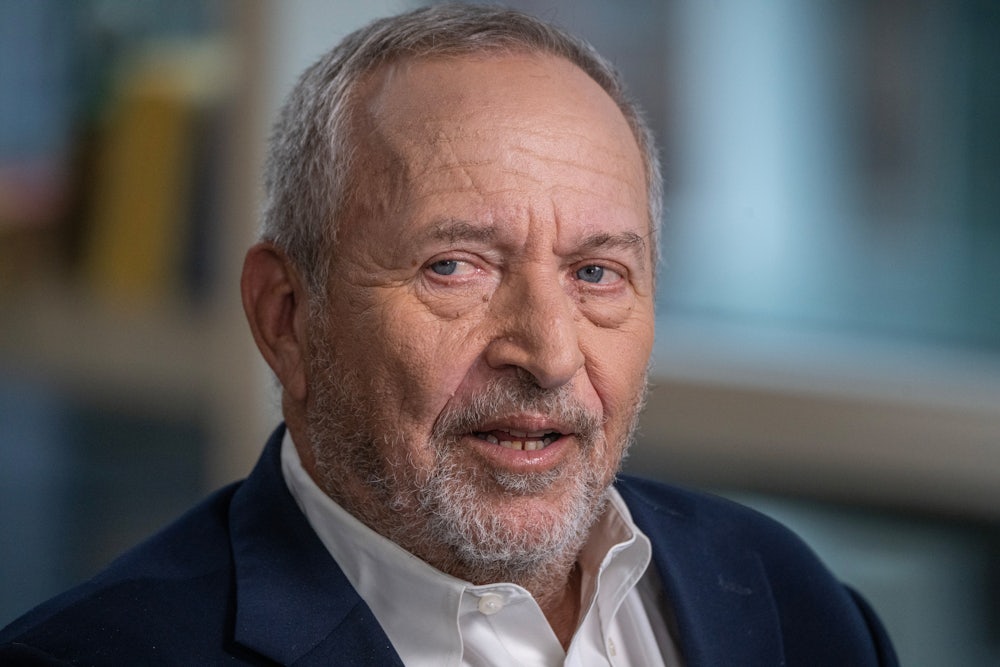

It seems Jeffrey Epstein’s tentacles reached much further than any of us could have imagined, with Larry Summers, one of the nation’s most prominent economists, being caught in the web. I have nothing to add to the specifics of his involvement with Epstein. It would have been better if his removal from public life had been caused by his more than three decades of wrongheaded policy advice.

Larry Summers has been at the center of economic policy debates since the early 1990s, when he took a top position in the Clinton Treasury Department after a brief stint as the chief economist at the World Bank. There, he was one of the architects of Clinton’s economic policy, from which we are still seeing the fallout today.

Clinton did have some progressive wins, such as expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit and raising taxes on the rich. And of course, the general economic indicators, especially during his second term, were impressive: Median household income shot up, as did median wages. And for deficit hawks, we got the first budget surpluses in three decades. But he was also responsible for trade policy that ultimately cost millions of manufacturing jobs, financial deregulation, and a boneheaded effort to cut Social Security that fortunately never got liftoff.

On trade, Clinton first pushed through the North American Free Trade Agreement, over the objection of the vast majority of Democrats in Congress. In his last year in office, he got Congress to admit China to the World Trade Organization, again over the objection of the vast majority of Democratic members of Congress.

China’s admission to the WTO, along with the high dollar policy pushed by the Clinton Treasury Department, led to a massive loss of manufacturing jobs over the next decade. In the 10 years from December 1999 to December 2009, we lost 5.8 million manufacturing jobs, more than one-third of the country’s total. These job losses devasted whole communities, where one or two factories were the major employers. Many have not recovered even today.

It’s also important to point out this massive job loss was a new story. There was only a modest drop in manufacturing employment in the three decades from 1969 to 1999.

It’s also wrong to call these deals “free trade” agreements. A key component of the trade deals negotiated in that era, especially the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS, provisions of the WTO, signed in 1994, was making patent and copyrights longer and stronger. These government-granted monopolies are 180 degrees at odds with free trade. However, they do redistribute a huge amount of income upward.

We will spend over $700 billion this year on pharmaceuticals that would likely cost around $150 billion in a free market without patent monopolies. The difference of $550 billion comes to $4,000 per household.

Intellectual property was not the only mechanism for redistributing income upward under Clinton. He also pushed through measures that gave the financial industry less oversight. Most notable in this respect was the repeal of the Glass-Steagall legislation, which removed barriers to the merger of investment and commercial banks. From numerous accounts, Summers was at the center of all this. And he was happy to take credit when Glass-Steagall was repealed and replaced by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.

Summers was also instrumental in nixing an effort by Brooksley Born, who was head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, to regulate credit default swaps. Credit default swaps subsequently played an important role in helping to further inflate the housing bubble in the 2000s, which in turn led to the Great Meltdown of 2008 and a worldwide recession.

The Clinton administration was also interested in cutting the annual Social Security cost-of-living adjustment, based on the claim that the consumer price index overstated the true rate of inflation. However, under pressure from unions and other progressive groups, it backed away from this position and never publicly advocated it.

After leaving the Clinton administration, Summers became president of Harvard but still remained very much involved in economic policy debates. He had dismissed any concerns about the stock bubble that was driving the economy in the Clinton years. The bubble’s collapse in 2000–2002 gave us a recession with the longest period without job growth since the Great Depression.

Summers was also dismissive of concerns about the growing housing bubble that drove the recovery from the 2001 recession onward. At an economics conference in 2005, Summers famously criticized Raghuram Rajan, who subsequently became head of the Central Bank of India, as a “financial Luddite” for raising questions about the complex financial instruments that were being used to support the housing market. As noted, the collapse of the housing bubble and the resulting financial crisis gave us the Great Recession, the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

But Summers wasn’t done. He was appointed to head the National Economic Council under Obama. The NEC is supposed to compile views on economic issues from various corners of the administration and present them to the president. Summers made the position the main focal point for policy under Obama.

There he played a key role in supporting the bailout of the banks, rather than letting the free market work its magic and downsize an incredibly bloated financial sector. In fact, he pushed for a bank bailout even before he joined the administration, pressing Democrats in Congress to support George W. Bush’s TARP bill, the $700 billion financial rescue bill, before the November 2008 election.

Once in office, Summers helped to engineer a grossly inadequate stimulus bill. He argued, plausibly, that it wasn’t possible to get a larger stimulus through Congress. But rather than trying to set the stage for further stimulus, Summers joined the team in proclaiming the success of the recovery, even as job growth remained anemic. The slow recovery, and the resulting weakness of the labor market, was undoubtedly a key factor in the economic discontent that fueled support for Trump in 2016.

Summers also wasn’t done on the trade front. A major initiative of the Obama administration was the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would have locked in industry-friendly rules in a variety of areas, most notably protection for pharmaceuticals.

Summers was not considered for a top slot in the Biden administration, either by his choice or by Biden’s. But that didn’t keep him from sharing his opinions. He was a harsh critic of Biden’s recovery package. He denounced the bill, as well as the low interest-rate policy of the “woke Fed,” as the most irresponsible macroeconomic policy in 40 years.

Summers’s criticism carried special weight given his status as a top official in the prior two Democratic presidencies. It was often cited not only by Republicans but also by Democratic holdouts like West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin. This helped to undermine efforts to add in parts of Biden’s Build Back Better agenda, such as expanded childcare subsidies, that were separated from the infrastructure bill that did pass.

For a time when inflation accelerated in 2021–2022, it looked as though Summers could have a point. But as inflation started to slow without the big jump in unemployment Summers said would be necessary, Summers argued that the consumer price index understated inflation, reversing his position from the late 1990s.

With inflation having fallen back almost to the Fed’s 2 percent target by the election, there seems little doubt that Summers was wrong in his assessment of Biden’s recovery package. There is even less doubt that Summers’s criticisms were not helpful in promoting a progressive agenda in the Biden years. For this reason, and his long prior history of misguided policy recommendations, Summers’s voice in policy debates will not be missed.

Of course, it may still be too soon to count Summers out. He has come back from the seeming political dead several times in the past, so we should not take for granted that Epstein’s ghost put a stake through his heart. But those of us who care about progressive economic policy can hope that we’ve seen the last time Summers will be calling the shots in a Democratic administration.