Early this year, having lost their majority in the November election, Senate Democrats put up a fight over a number of President Trump’s Cabinet picks. But Marco Rubio wasn’t one of them. The Senate unanimously confirmed him as secretary of state in January—for two reasons.

First, Rubio spent over a decade in the Senate, which is one of the world’s chummiest and most insular legislative bodies. And second, the former Florida senator had built a reputation as level-headed, reasonable, and compromise-minded—at least by the standards of the MAGA-era Republican Party. Senate Democrats no doubt were relieved to have Rubio running the State Department rather than, say, Steve Bannon.

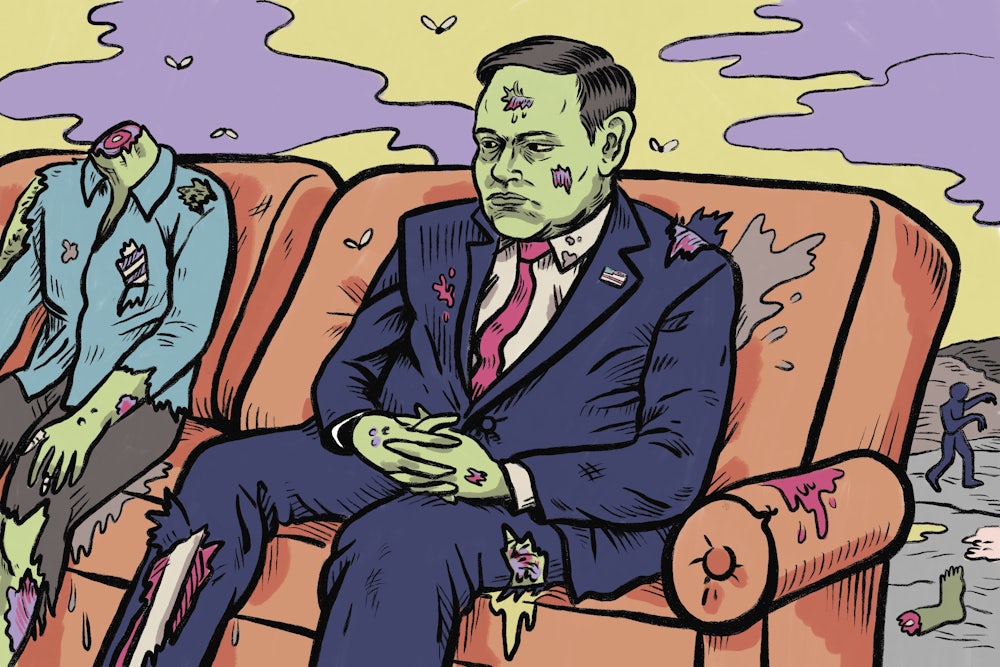

You no doubt remember the “adults in the room” reporting meme during Trump’s first term: a reference to establishment figures in the administration who, it was believed, brought much needed stability and experience to a presidency that sorely lacked both; these men would temper Trump’s worst instincts. But come January, Trump 2.0 was shaping up much differently. He was sick of adults; his administration was going to be stuffed to the gills with crazies, losers, and incompetents. Rubio was an exception, however. He would be an adult in the room—perhaps the only one.

One could argue that has been true. Yes, Rubio—who has since added the titles of acting national security advisor and acting national archivist to his portfolio—has had his share of foolish moments, like his recent order changing the State Department’s default communications font to Times New Roman because Calibri font was too woke. But for the most part, especially compared to colleagues like Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth (a murderous dimwit) or Attorney General Pam Bondi (just a dimwit, but a very big one), Rubio has run a tight ship. While Trump’s second term has been defined by gross overreach, incompetence, and chaos, the State Department has largely gone about its business without drawing controversy.

But that’s the problem—Rubio’s work this year should be controversial. Since assuming office, he has transformed the State Department into a ruthless and effective arm of the administration’s larger push to quash dissent and demonize and punish immigrants, both legal and undocumented. Perhaps more surprising, given his long record as a foreign policy hawk, he has slavishly worked to remake American foreign policy to Trump’s precise specifications: unraveling longstanding alliances and cozying up to dictatorial regimes while making the world a more dangerous and unstable place. Now, as the year draws to a close, he is pushing the United States toward war.

Less than a decade ago, Rubio saw Trump with clear eyes. Trump, he argued during his doomed campaign for the GOP presidential nomination, was a demagogue. “This is a political candidate … who has identified that there’s some really angry people in America,” Rubio said. “They feel as if they’ve been mistreated by the culture, by society, by our politics, by our economy… And along comes a presidential candidate and says to you, ‘You know why your life is hard? Because fill in the blank – somebody, someone, some country – they’re the reasons for it. Give me power so I can go after them.’”

It was telling that Rubio didn’t fill in the blanks. On some level, he knew that directly calling out Trump for vilifying Mexicans, Muslims, immigrants would have been the kiss of death for a campaign that was already on life support. But Rubio understood that Trump was preying on the racism and resentment of the Republican base to accrue power; he knew that Trump’s project would not end there. Having told his voters that he was the solution to all of their problems—and that minority groups were their principal cause—Trump and his movement could only move in one direction: despotism.

In the desperate, final days of his 2016 campaign, Rubio likened Trump to a “third-world strongman.” He was right. A decade later, Trump is leading an increasingly authoritarian administration that is defined by fascistic shows of force, brazen and historic corruption, and a fierce determination to undo the American constitutional order and remake the federal government in his own image. But now, one of his most effective allies in that project is Rubio himself.

Rubio spent the spring engaged in a draconian crackdown aimed at foreign college students, many of whom attracted the ire of the administration for engaging in constitutionally protected free speech related to the United States’s support for Israel’s genocide in Gaza. After having their visas revoked by the State Department in response to pro-Palestine activism, graduate students were, in some cases, essentially disappeared: Detained and escorted into unmarked cars by plainclothes officers who neither identified themselves nor presented a warrant. Rubio’s war against foreign students had two primary goals: to create a chilling effect by using the full force of the government against those who spoke out against it; and to make it clear that the United States, which once warmly welcomed millions of foreign students, was closed.

On both counts, it worked. Rubio not only ordered this crackdown, he eagerly and effusively defended it, claiming that it was a foreign policy necessity to remove students whose nonviolent activism he insisted was terroristic and fundamentally un-American. The students, Rubio said, had been given visas to study not to “become a social activist tearing up our campuses.” Never mind that the students whose visas he revoked had never been accused of violence or hate speech.

Rubio also played a key role in the administration’s deportation of people to a notoriously violent superprison in El Salvador. In February, he met with Nayib Bukele, the country’s crypto-obsessed (and very corrupt) president, who offered to jail undocumented migrants in the U.S. who have been convicted of crimes. Rubio touted it as “an act of extraordinary friendship” and “an example for security and prosperity in our hemisphere.” Of course, we know what then happened: Many of the people the U.S. sent to El Salvador had never been convicted of crimes, and some were sent there accidentally.

Despite his long record as not just a foreign policy hawk but as a particularly fierce critic of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin, Rubio has enthusiastically worked to advance Trump’s larger goal of ending the war in Ukraine on terms that are remarkably friendly to Russia. Though Putin started the conflict by invading Ukraine, Rubio has aped Trump, insisting it is “not our war” while blindly regurgitating Moscow’s blinkered description of it as a “proxy war” that Ukraine (and its NATO allies) was actually responsible for starting. Rubio has not only demanded Ukraine make concessions to the nation that invaded it, but repeatedly threatened to cut off aid if it does not. All the while, he has worked to cut it out of negotiations to end the war altogether, crafting settlements directly with Russia that are then foisted on the Ukrainians as a fait accompli. It is a “peace” that would double as a Russian victory, a settlement that would only make a future, more destructive conflict between Russia and the West more likely.

As with the centerpiece of Trump’s pathetic campaign for a Nobel Peace Prize—the absurd claim that he has “ended” eight wars—Rubio’s interventions in Ukraine are misleading. American foreign policy is more transactional under Rubio and Trump, but is not more isolationist or less hawkish—or, for that matter, more oriented toward peace. Far from it. In June, Rubio risked a regional war by backing the U.S. bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities; over the course of the year, he has made a global war more likely by increasing tensions with China. Now he is steering the U.S. toward regime change, this time in Venezuela.

Hegseth will take the lion’s share of blame if the U.S. ends up in a military quagmire in Venezuela, since he’s overseeing the military buildup in the southern Caribbean and illegally blowing up boats that he claims are drug traffickers tied to Nicolas Maduro’s socialist government. But make no mistake: Regime change in Venezuela is Rubio’s project. Rubio has reportedly spent months building the case for taking out Maduro, who has ruled the country since 2013, and only found success after he hit on a preposterous rationale that nevertheless convinced Trump: Venezuela is shipping huge quantities of drugs to the United States. (Never mind that Venezuela doesn’t produce fentanyl, and probably less than 10 percent of the cocaine in the U.S. passes through that country.)

The son of Cuban exiles, Rubio is deeply committed to ending communism in his parents’ homeland. He considers the Maduro regime evil because it is socialist, and—preposterously—believes that overthrowing it would weaken Cuba. As The New York Times recently reported Rubio “is a primary architect of an escalating military pressure campaign against Venezuela. And while pushing out Mr. Maduro appears to be one immediate goal of U.S. policy, doing so could help fulfill another decades-long dream of Mr. Rubio’s: dealing a critical blow to Cuba.” This obsession with ending communism and socialism is one way in which Rubio has not changed since Trump’s rise, and it might lead to another stupid, avoidable war that causes untold death and destruction.

It’s worth revisiting the old Rubio, from 2016. Has he really changed? Or was it foolish to ever believe he was a principled politician? Rubio has long desired political power beyond the Senate, and has tried to play the angles in Washington accordingly. The Rubio who called Trump a “third-world strongman” was making a bet that Trump would fail—and that, when he did, his fellow Republicans would turn to someone who had seen the light before they did. Someone like Marco Rubio. That turned out to be a terrible bet, as Trump is now ruling America very much like a strongman. Rubio is helping him because he’s making another bet: that voters will reward his work as one of that strongman’s most effective lieutenants. He was only ever ambitious, it turns out. He has no principles to betray—except one, which may end up getting a lot of people killed.