April 19:

I leave my hotel earlier than I need to and walk down from the Washington Monument to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Even at 7:30 a.m. the Mall is nearly deserted, the Lincoln Memorial empty. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, on the other hand, is teeming with people who appear to have been up for hours, walking slowly along the length of the black marble slab bearing the names of the dead. For the next twenty minutes I sit on a bench dodging bird droppings and waiting for Senator John McCain, who has agreed to meet me here. In my attempts to spot him at a distance I can’t help but notice how differently ordinary people behave from politicians. Maybe fifty likely candidates pass through my line of vision, and not one of them could pass for a U.S. senator at 100 paces. They comb their hair in public, scratch themselves, hold hands.

At eight on the button McCain appears at my side, looking very senatorial except for a pair of outrageously wide black aviator sunglasses with some undignified name—Hobbie? Hippo?—stenciled on the earpiece. He takes the seat on the bench beside me, and for a brief moment I feel I am in one of those movies about Washington in which the clueless protagonist gleans some crucial piece of information from the terrified insider, who is constantly glancing over his shoulder. Except that there is no single piece of information I know enough to seek, and McCain long ago decided he was going to be seen with whomever he pleases.

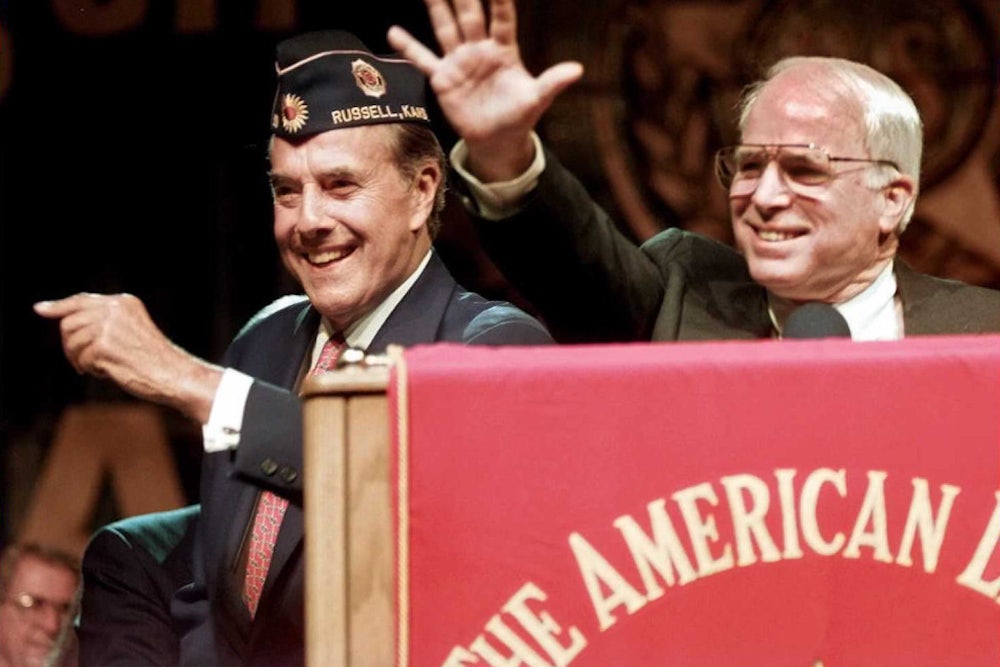

The campaign has moved into the legislature. Except for a handful of tactical speeches and photos, the candidates will shape public opinion of themselves on the job. The net effect of this is to turn up the heat on the Hill, and senators with nerve are going to exploit the moment. In a couple of weeks, for instance, McCain will rise on the Senate floor and attach his campaign finance reform bill to some unrelated piece of legislation. This will embarrass Bob Dole, who will be forced to fight reform.

What makes this so interesting is that McCain is the Dole surrogate most in demand as a speaker around the country—and it’s not hard to see why. Few Republicans seem to care about the differences between the two men—though they might soon care more. For the moment what matters most to the people who wish to see McCain speak for Dole is the formative experience that the two senators ostensibly share: both nearly died in a war, both endured indescribable pain and suffering. Dole’s ordeal is at the center of his national campaign—to some extent it is his campaign. McCain’s trials are less known. On October 26, 1967, when he ejected out of his Navy jet and into a North Vietnamese mob, McCain suffered two broken arms, a shattered knee and shoulder and bayonet wounds in his ankle and groin. Robert Timberg’s gripping book, The Nightingale’s Song, depicts McCain two months later, in his first prison cell:

McCain weighed less than one hundred pounds. His hair, flecked with gray since high school, was nearly snow-white. Clots of food clung to his face, neck, hair and beard. His cheeks were sunken, his neck chickenlike, his legs atrophied. His knee bore a fresh surgical slash, his ankle an angry scar from the bayonet wound. His right arm, little more than skin and bone, protruded like a stick. But it was McCain’s eyes that riveted his cellmate George Day. “His eyes, I’ll never forget, were just burning bright. They were bug-eyed like you see in those pictures from the Jewish concentration camps. His eyes were real pop-eyed like that. I said, the gooks have dumped this guy on us so they can blame us for killing him,’ because I didn’t think he was going to live out the day.”

McCain survived in captivity without medical treatment for the next five years, enduring torture so exquisite that even to read about it causes sweat to pop out on your brow: his captors would hang him by his broken arms from dangling ropes for hours on end, for instance. But the astonishing part of McCain’s experience was its voluntary aspect. McCain is the third generation of a distinguished military family; his father was an admiral during the Vietnam War. The North Vietnamese hoped that this famous prisoner of war would violate U.S. military policy, which dictated that prisoners be returned in the order they arrived. In accepting their offer of freedom McCain would testify to the demoralization of American troops. For five and a half years his captors tried to torture him into going home. For five and a half years he refused to go.

As McCain reminisces, I realize I have made a tactical mistake. I am in the wrong place at the wrong time. I had hoped to talk to McCain about his relationship to Dole—and especially his plans to saddle Dole with a campaign finance reform bill. But it feels obscene to talk about such things in such places. My blunder is what the speculator George Soros calls a fertile fallacy, however. All by himself McCain is leading the conversation in a direction well worth following.

We walk alongside the black granite slab against the oncoming traffic, then back again. The tourists pass us, stopping to get the feel of the place and to read the names. One sign of the memorial’s success, I say, is that it has followed a path similar to those it seeks to commemorate. Like the veterans themselves, it has gone from being feared and loathed to being widely revered. The Park Service says the memorial has become the second most frequently visited site in Washington, after the Capitol. McCain admits that at first he found it depressing and even faintly antagonistic. But one day he was passing through on his own—he visits often by himself—and discovered a couple of veterans running their hands across the inscribed names. Clearly the two men had never met before, but they had fallen into conversation, swapped war stories and in a few minutes were clutching each other and weeping. “If that kind of healing goes on,” says McCain, “well, then it’s a good thing.”

Someone once said that an explanation is where the mind comes to rest. There is a feeling about McCain—one that seems lacking in Dole—that he has somehow explained his own experience to himself. He has assimilated his trauma differently than the candidate he’s behind. “This is the McCain theory—and I think it’s valid,” he says. “I was an adult when I was shot down—31 years old. I’d had a whole life. He was 19. What were you like when you were 19? I believe that everything Bob Dole has done since the war was dictated by that experience.” The Vietnam veteran has achieved the kind of equanimity that is supposed to be vouchsafed only to veterans of good wars. When Clinton arrived at the White House, for instance, McCain sent him a note saying that any time the president wished to walk down to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial the senator from Arizona would be glad to walk alongside him. Clinton sent back a nice note.

Recalling this exchange causes McCain to break his rhythm. We are walking back toward the bench, and McCain is limping slightly, like a high-school football star. He is remembering something else. “I don’t know if you want to write about this,” he begins. “Back in the mid 1980s a guy who protested the war came into my office. He said his name was David Ifshin.”

In December 1970 David Ifshin had led a group of American students to Hanoi, where he delivered an anti-war radio address to American soldiers engaged in attacks on North Vietnam. Like other anti-American propaganda, his program was piped into McCain’s prison cell from six in the morning until nine at night. But McCain, who can generate anger in a heartbeat, shows not the faintest trace of resentment. “Ifshin stood in my office,” he explains, “and he said, I came here to tell you that I made a mistake. I was wrong, and I’m sorry.’ And I said to him, Look, I accept your apology. We’ll be friends. But more importantly I want you to forget it. Go on with your life. You cannot look back.’”

Here he pauses, and I figure he’s finished. But he’s groping behind his aviator sunglasses for the point of his anecdote—that forgiveness is ultimately less self-destructive than the bitter desire for vengeance. Or perhaps that there is no such thing as vengeance. Five months ago David Ifshin was diagnosed with cancer. The cancer has proved untreatable and has spread rapidly. David Ifshin is now dying. He is 47 years old and has a wife and three young children. “When I heard about it,” says McCain, “it did pass through my mind: Suppose I had told David Ifshin to get the hell out of my office. How would I feel about myself now?”

April 23:

I’m walking out the door of my Washington apartment on my way to find David Ifshin when John McCain calls. I’ve made the mistake of telling his press secretary what I’m up to, and she’s passed it along to the senator, who is seriously concerned. “Look, I don’t mean to insult you,” he says, “but be careful with this. If you wrote anything that hurt David or Gail or the kids—the Ifshins have three young children—I’d never forgive myself. I’d forgive you, but I wouldn’t forgive myself.”

It’s a half-hour drive out of Washington to the Ifshins’ house in the Maryland suburbs, where I find a gaunt bearded man stretched out on a patio lounge chair, attended by his wife, Gail. This afternoon he is tired, and his voice is barely audible as he sketches his political career.

The cover of Life magazine of April 23, 1971, shows David Ifshin, aged 22, at a war rally, wearing a collegiate goatee. He’s standing directly behind Jane Fonda, who has her fist raised. After his war protests he worked on a kibbutz; but when he returned to America he also returned to national politics. He went on to work on the Mondale campaign and, to a storm of protest, was even tapped to head the Dukakis transition team. He spent ten years as general counsel to aipac. He had met Clinton briefly in 1972; twenty years later, when Clinton ran for president, Ifshin became general counsel for his campaign. Before he accepted the job, he told Clinton he’d been attacked for his war record each time he’d joined a presidential campaign. “I brought it up with Clinton deliberately,” he says, “and he said he knew what I had done and admired it then. And that he still admired it now.”

The past is especially stubborn these days, and Ifshin’s work with Clinton is still landing him in the news. He makes an important cameo appearance in Blood Sport, for instance, James B. Stewart’s book about the Whitewater scandal. “Get the facts, get them out, and get it over in a single day,” he tells Mickey Kantor on page 210, when the story first breaks in The New York Times. Kantor first agrees to send a team of lawyers down to Little Rock and get to the bottom of the thing. But later—presumably after speaking with the Clintons—Kantor changes his mind. “If you don’t level with them,” Ifshin tells Kantor prophetically, “you’ll wind up with a special prosecutor.”

Having broken with the campaign, he is now back in touch with the candidate, who calls Ifshin two or three times each week, even when he’s traveling. A few months ago the Ifshin family—David, Gail and their three children—spent the night in the Lincoln bedroom. In the pictures of Clinton playing with the children the president’s ruddy good health seems almost obscene beside Ifshin’s drawn face. Yet, when I called, David Ifshin did not hesitate to rise to the occasion. “I’m very proud of this story,” he says, “and it’s never been written.” I ask him about his feelings toward McCain. “One of our true political heroes,” he says. “He’s a giant.”

Ifshin’s version of their story differs from McCain’s in its important details and in its spirit. The way McCain tells it, Ifshin is the hero: he decided he’d made a mistake and bravely took responsibility for his actions. The way Ifshin tells it, McCain is the hero. As I listen to him I realize that this is the reverse of the usual Washington investigation, in which the reporter visits each interested party to collect the dirt on the adversary. Here is a case where each is needed to explain the other’s nobility of spirit. I have never heard two political allies, much less two political opponents, cast each other in a more flattering light.

“I had always wanted to apologize,” Ifshin begins, “but did not know who to apologize to.” His moment to act, he decided, came at an aipac meeting around 1986 at the Washington Hilton. Ifshin spotted Senator John McCain at a distance and decided that he was the man who deserved the apology. “I hoisted my courage up and went over to him,” recalls Ifshin, “and before I could get a word out McCain said, I owe you an apology.’” A couple of years earlier, during the 1984 presidential campaign, McCain had given a speech in which he attacked Ifshin’s war record. “Basically someone had handed him a script,” said Ifshin, “and he read it. He was sorry he did it and said he wouldn’t do that kind of thing again. Then he asked me to stop by his office, which I did. And normally wouldn’t do. It was blind fate, I told him at that time. I said, I owed you an apology, and you robbed me of the chance to make it’—and he was characteristically modest and humble about it.” Later that year McCain and Ifshin, together with a Vietnamese emigre named Doan Van Toai, established the Institute For Democracy in Vietnam.

Ifshin shifts painfully in his chair and stops to catch his breath. It was at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial that what he calls “the second half of the story” with McCain began. On Memorial Day of 1993 Clinton spoke at the site. Both McCain and Ifshin were present. Clinton was cheered loudly. He was also heckled. And one of the hecklers waved a sign that said: “tell us about ifshin.”

Four weeks later Ifshin found himself on a flight to Washington with McCain, who motioned for him to take the seat beside him. “He asked why I hadn’t taken a job in the administration. I said this and that. We played twenty questions until finally he said, It’s because of that stupid sign isn’t it?’ And I said, Yes, partly, it was.’ And he said, Come to my office tomorrow morning and we’ll settle this thing once and for all.’”

The next day, June 30, 1993, David Ifshin turned up in John McCain’s office in the Russell Senate Office Building to find that the senator had drafted a letter, which he entered later that day in the Congressional Record. It began by praising Clinton’s Memorial Day address on behalf of Vietnam’s veterans. The veterans, McCain wrote, “were very impressed by Clinton’s determination to offer an eloquent tribute to their service when it would have been far easier for him to have avoided the event altogether.” He decried the behavior of the protesters. Then he moved on:

Among the demonstrators that day, one individual held a sign which asked the president to explain his association with a person known to many of our colleagues, Mr. David Ifshin. “tell us about ifshin,” it read. My other purpose in speaking today is to do just that: I want to talk about David Ifshin. David Ifshin is my friend...