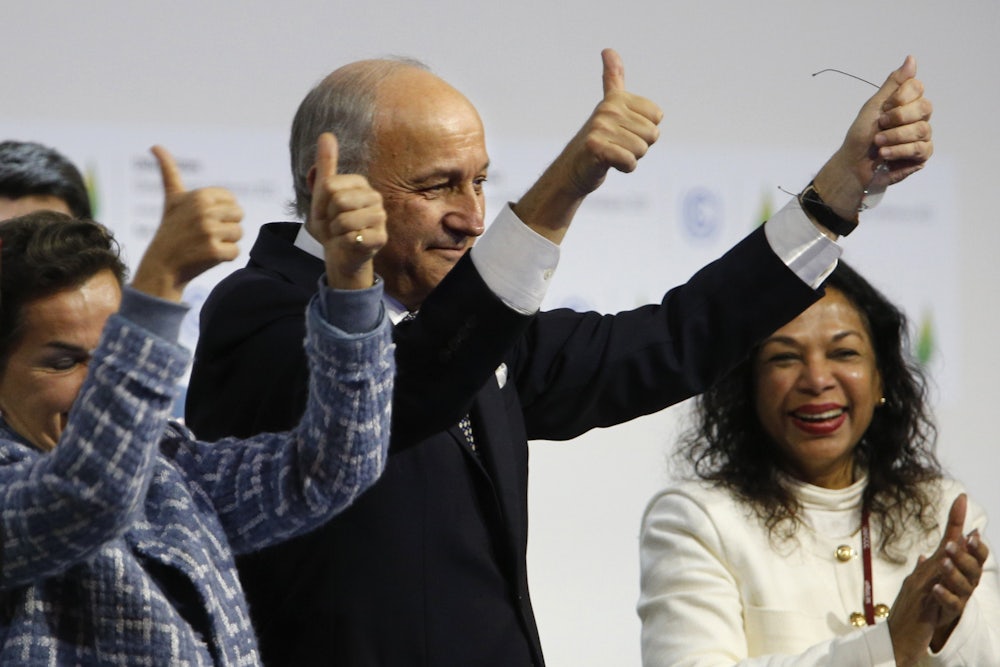

There was uncertainty to the very end of the Paris summit, down to the final moments when the U.S. delegation demanded a change to a single typo in the draft text. Then the confusion finally cleared. After running into overtime on Saturday, the two-week Paris climate conference ended with a deal. “We met the moment,” President Barack Obama said in a victory speech from the White House on Saturday.

Did the agreement save the world? As long as you had moderate expectations headed into Paris, you won’t be disappointed. The 31-page agreement did more than the relatively low bar set for it. Indeed, it represents a powerful step in curbing climate change as the first deal that covers every major polluter. “For the first time in history, the global community agreed to action that sets the foundation to help prevent the worst consequences of the climate crisis while embracing the opportunity to exponentially grow our clean energy economy,” the Sierra Club’s Michael Brune said. Some longtime climate advocates, such as Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, offered more qualified praise. “While this is a step forward it goes nowhere near far enough,” the presidential candidate said. Environmental groups with high expectations for Paris were sorely disappointed, however. “The Paris Climate Agreement is not a fair, just, or science-based deal,” Friends of the Earth said.

Ahead of the conference, Rebecca Leber outlined six keys to success in her feature article previewing the talks. Here we give you our final verdict on whether the COP21 agreement achieved those goals.

Here’s a roundup of the biggest news from around the conference:

- Though the final text is aspirational and far from perfect, it does show momentum for further climate action. (New Republic)

- Jonathan M. Katz, reporting from Paris, writes on the sense of relief that overtook Le Bourget after negotiators eked out a final agreement. (New Republic)

- Get ready for the COP21 hangover. Global warming is far from solved. (New Republic)

- How a South African negotiation technique carried the climate negotiations. (Quartz)

- Despite the protest ban, activists had the last word in Paris—and many said the agreement does not go far enough. (Grist)

- John Kerry defends the agreement after James Hansen, climate activist and former NASA scientist, said the talks were a fraud. (The Guardian)

- Other activist groups applauded the agreement as a turning point in history. Read a round-up of organizations’ statements. (Inside Climate News)

- The crucial difference between “should” and “shall” in negotiating a global agreement. (The ABC)

- The aviation industry is a top emitter not covered by the climate talks, but a global deal should come next year. (Climate Central)

- A breakdown of the top five key points of the final agreement. (Mashable)

Read our previous progress reports: