This year, some of the most trusted science institutions in the world participated in a high-profile and disastrous national mismanagement of the coronavirus pandemic. In February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention insisted on creating its own tests, rather than using ones developed by the World Health Organization. The CDC-backed tests were then plagued with inaccuracies and shortages. Then the Food and Drug Administration authorized a series of treatments and tests with little or no apparent oversight: hydroxychloroquine, adopted on the scantest of evidence; antibody tests, OK’d for use without review of their accuracy; convalescent plasma, the benefits of which were massively overstated.

The CDC refrained from commenting on the issue of public mask-wearing until April, when officials wanted to recommend mask-wearing in all areas of the country, but the White House insisted on emphasizing it was “voluntary” in high-transmission zones. It took until July for the CDC to say that face coverings are a “critical” tool for ending the pandemic. Then, in August, the CDC inexplicably changed its guidelines to say asymptomatic people didn’t need to be tested after exposure, only changing them back in September as cases once more began to surge. Meanwhile, political appointees at the Department of Health and Human Services tried to change results in CDC research reports and edited CDC guidance and press releases. There has been no unified plan from federal agencies to coordinate a response to the pandemic with states. All along, President Trump pushed the idea that the FDA could rush a vaccine by Election Day and stifled any experts who disagreed with his plans.

Managing the response to a pandemic is never easy: No matter how many simulations you run and handbooks you create and trainings you conduct, there will always be bumps in the road. But with unprecedented political interference and some major missteps, U.S. agencies like the CDC and the FDA have taken massive blows to their credibility. With a new administration starting January 20, experts say a top priority should be rebuilding that trust in the country’s top medical and scientific institutions, which should issue guidance and regulations based on evidence and science, not politics. But the road will not be easy, they say, and some of these missteps have revealed glaring and long-standing vulnerabilities in the firewall between politicians and top scientists.

Many members of the scientific community are now in open revolt against the agencies, with former National Institutes of Health director Harold Varmus co-authoring a New York Times op-ed in August telling Americans to “ignore the CDC.” The public has also lost faith. Between April and September, trust in the CDC dropped from 83 percent to 67 percent, according to a poll from the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. Among Republicans, the loss of trust was even more dramatic, falling by one-third in just a few months. Regardless of affiliation, about four in 10 U.S. adults believe both the CDC and the FDA have paid “too much attention” to politics when it comes to setting guidelines and authorizing treatments.

Within federal agencies, former officials have described relentless political pressure making their work difficult or impossible and crushing credibility in the process. “Every time that the science clashed with the messaging, messaging won,” Kyle McGowan, the former chief of staff at the CDC, told The New York Times earlier this month. Across federal agencies, scientists have left the Trump administration in droves.

Under previous administrations, whether Democratic or Republican, people broadly trusted CDC and FDA recommendations, Dr. Ashish Jha, the dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, told me. Informing his patients or other clinicians that “the CDC or the FDA recommends” something was “shorthand for good science,” he said. “It meant that this was good public health guidance, based on data. There wasn’t going to be political interference,” Jha said. “And we have, in the last 12 months, managed to undermine … decades of hard work to build up that trust. And the repercussions are going to be substantial, and they are going to last a long time.”

Much of the damage stems from the Trump administration pressuring scientists to change guidelines or research findings, or to speed up authorizations of treatments, tests, and vaccines. “The president stood up and said, ‘This is what we’re going to do, and this is what I’m telling the FDA to do.’ And that’s got to stop,” Jha said. “You’ve got to hear directly from the FDA and CDC leadership.”

“Trust in the scientific process, trust in scientists has been dismantled—and it feels like deliberately, by the current administration,” Dr. Seema Yasmin, an author, medical doctor, and journalism professor at Stanford University, agreed. “You’ve also had censorship with federal agencies like the CDC, where guidelines have been amended by the White House because they’re not what the White House wanted to see,” she said. Without trust in these agencies, no one will want to use the products they have quickly approved. Now that we have vaccines, she said, it’s important that the public understand they result from decades of work prior to the pandemic, and this scientific innovation—not political pressure—was why they were able to be produced in 11 months instead of 11 years.

Despite the speedy vaccine development, the FDA has also made blunders, Jha said. “The way the FDA has handled this vaccine, the Pfizer vaccine, has been nothing short of terrific. They’ve been superb. Just superb. But the way they handled the convalescent plasma was a disaster.”

Authorizing treatments and tests for emergency use was understandable, Dr. Jeremy Faust, an emergency physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and instructor at Harvard Medical School, agreed—but not without compelling evidence and oversight. For instance, he said, it authorized the use of hydroxychloroquine “based on the thinnest and most amateur dossier of evidence I’ve ever seen.” When FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn erroneously hyped the benefits of convalescent blood plasma, Faust added, “it appeared to be as a result of political pressure, because there’s no other explanation for why they’d get it wrong. And it’s unimaginable to me that any other administration, whether it’s a prior Republican administration or the next Democratic administration, would put the kind of pressure, in public, on the FDA.”

One of the top things the incoming Biden administration can do, experts told me, is reestablish the norm of having the agencies speak for themselves, rather than the White House influencing the messaging. During the anthrax attacks of 2001 and the Ebola outbreak of 2014–16, Presidents Bush and Obama, respectively, “weren’t the primary spokespeople,” Jha said.

Appointing trusted scientists at the helm of the agencies—and allowing them to conduct briefings and communicate the science—will help. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, was recently appointed director of the CDC by the incoming Biden administration. “We are ready to combat this virus with science and facts,” Walensky said on Twitter upon the news of her appointment, in a stance that shouldn’t have seemed radical but, in 2020, was.

Walensky is known as a “savvy communicator“ who enjoys seemingly universal renown among her public health colleagues, including those with whom I spoke. Faust, who has worked with and co-authored studies with Walensky, sees her as a mentor. “Her appointment to lead the CDC signals a new day. It signals that scientific expertise and a long track record of understanding the issues is what matters,” he said.

But changes are coming even before the new appointees enter office, Faust pointed out. “The noose around the CDC,” he said, is slowly loosening, with CDC experts resuming some briefings. “The palpable sense of relief right now is notable,” Faust said. “Their guidance has been increasingly relevant, less politicized, and more a reflection of scientific consensus that’s emerging. So, I think we’ve already seen improvements from the CDC.” Faust said regular, even daily, briefings are really important, as well as consistency, instead of conflicting briefings from different experts at seemingly random times.

“If you ask right now, ‘What is the CDC guidance on schools?’ I can show you on the CDC website a bunch of different documents that are clearly in contradiction with each other. And that makes people say the CDC doesn’t know what it’s doing,” Jha said. Instead, these decisions need to be guided by the best available science, and the agencies’ guidelines need to be clear and coherent.

For the FDA, experts agreed, the most important goals will be transparency and independence from political interference. “There’s going to be times when it’s a close call, and it’s hard to say, and there are going to be times when it’s a slam dunk. And I think it’s useful to know which ones are which,” Faust said. “There have been mistakes. It’ll take time for those to be in the rearview mirror. And it’ll take a few wins for people’s confidence to be restored.”

But it’s not enough simply to lead with good science. When great damage has been done, the root causes of that damage need to be addressed, experts said. “The very real questions, anxieties, and fears and concerns of the American public have to be addressed. There’s no way that you can just hit people with a data, or just with a blanket message that these vaccines are safe, if you’re not dealing with the root causes of distrust in science and the scientific process,” Yasmin said.

That means accountability for the disasters of 2020: figuring out what went wrong and how to prevent missteps like these in the future. “There probably has to be a careful examination of the agencies, and beyond just political interference,” Jha said. “Are there things that the agencies didn’t do as well as they should? I certainly think that is true. And those need to be addressed as well.”

Part of that process will be figuring out how to build more guardrails against political interference. Trump has shown that putting pressure on independent agencies is shockingly easy: The barrier between politics and science was based on norms, Jha said—unspoken rules and gentlemen’s handshakes. Is it enough, Jha asked, to have political leaders who vow not to meddle in science? “Or do you need to actually do something else to create a firewall?”

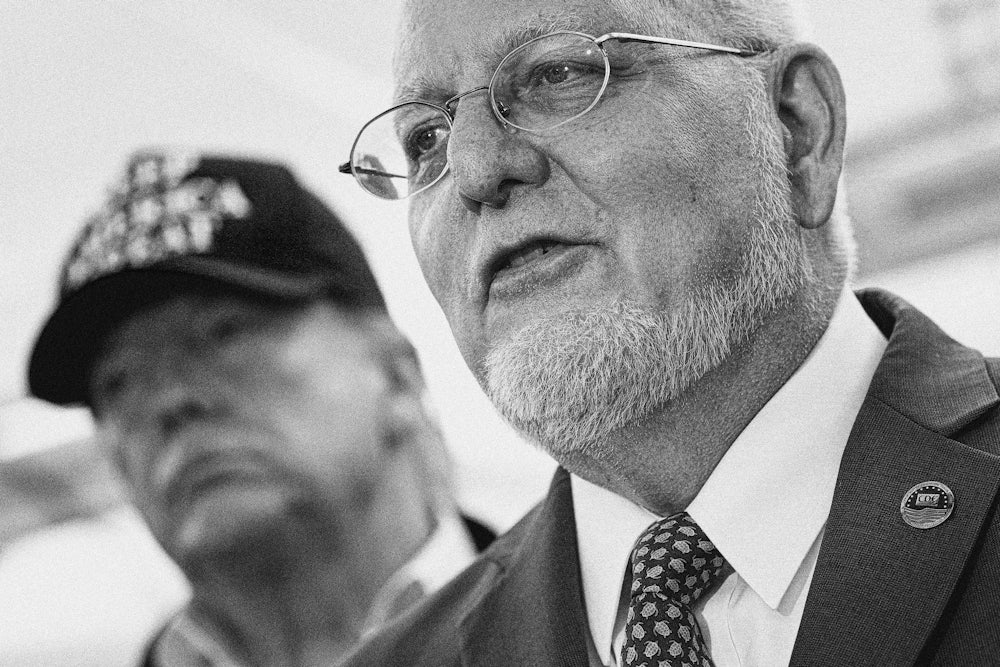

Documenting and standing up to public political pressure is one way to push back against undue influences. Former CDC director Dr. William Foege, in a private letter in September, urged the embattled current director, Dr. Robert Redfield, to document all of the political interference he encountered and to stand up to political pressure even if he lost his job. “When they fire you, this will be a multi-week story and you can hold your head high,” Foege wrote. (The letter was later leaked to USA Today, and Redfield instead mostly acquiesced to White House pressure.)

Another solution might be putting up barriers between agency leaders and the politicians who appoint them. Civil servants, such as Dr. Fauci, tend to have more freedom to do their jobs because it’s harder to fire them if they contradict an administration’s stance (a rule Trump has sought to weaken). But political appointees can be dismissed by the White House, thus making them more vulnerable to political whims. This could be changed by setting up an independent board or panel of federal judges to review senior officials’ performance, to guard against arbitrary or politically motivated firings. Congress could also serve in review capacity, rather than merely being involved in the confirmation process.

Some health experts have also proposed a process similar to the 9/11 Commission or a truth and reconciliation commission. “I think it would do great damage to the United States, as a whole, if there was no form of accountability for the decisions that have been made,” said Dr. Alexandra Phelan, a global health lawyer and assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at Georgetown University. “It’s unfathomable to put what have been governance failures at the feet of a virus,” she said, when the virus hasn’t ripped apart other countries as it has the U.S.

Last week, the bells at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., rang 300 times for the 300,000 Americans who died from Covid-19 this year. How many of those deaths may be attributed to decisions made by this administration? If we never know the answer, and if we never address the errors, the next disaster could be even worse.