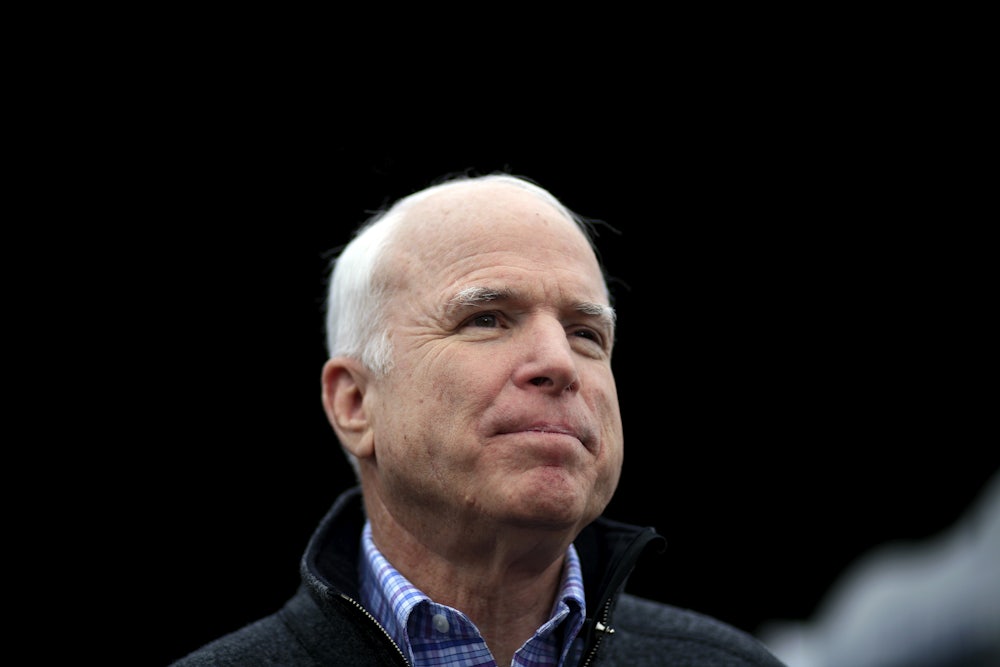

In 2014, the late Senator John McCain quietly slid a dagger into the backside of the Arizona tribal nations he was ostensibly elected to represent. Deep in an appropriations package for military funding, McCain tacked on a rider, known as Section 3003. The rider accomplished what the Arizona Republican had been trying to do through standalone legislation since 2005—hand over 2,400 acres of sacred Apache lands to the mining company Rio Tinto, which has long eyed an area known in the English tongue as Oak Flat for the massive deposits of copper that rest miles beneath its surface. Speaking with the Tucson Sentinel in 2012, two years before his midnight rider, McCain called the proposed transfer, “an economic opportunity that shouldn’t be squandered.” Although both the White House and Senate were controlled by the Democratic Party at the time, President Barack Obama signed the bill, with Section 3003 intact, into law, against the repeated objections of tribal nation leaders. Six years later, McCain’s vision is now on the cusp of becoming reality.

Earlier this week, the grassroots group Apache Stronghold—consisting of citizens of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, among others—offered one final act of resistance to this bipartisan land grab. The Stronghold filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Forest Service, seeking to block the January 15 release of the agency’s official Oak Flat environmental impact review, which will trigger the land transfer to Resolution Copper, Rio Tinto’s mining outfit. But on Friday, the Trump administration, ignoring the lien Apache Stronghold had filed on the land to keep the transfer from happening while the case is heard in court, issued the environmental review, officially approving the land swap and potentially signaling the permanent desecration of the Apache’s sacred lands.

Located in what is now the Tonto National Forest, the area of Oak Flat, known as Chi’chil Bildagoteel, is a sacred place that, since time immemorial, has hosted the Apache tribal nations’ Sunrise Ceremony, a traditional rite of passage for Apache youth. Through both treaty and congressional action, Chi’chil Bildagoteel has been protected from development even as the United States has driven the San Carlos Apache from their ancestral homelands. In 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower issued the Oak Flat Public Land Withdrawal Order, or P.L. 1229, forcefully removing the Apache from the area containing Chi’chil Bildagoteel, but with the promise that the 760 acres would be shielded “from all forms of appropriation under the public-land laws, including the mining but not the mineral-leasing laws.” (The action was not done to protect the Apache’s sacred grounds but to “protect the Federal Government’s interest in the capital improvements of the campground that exists there.”)

Pro-mining arguments have hinged on the idea that, due to the 1955 withdrawal order, Oak Flat’s value to the Apache is historical, not current—although why this would make its destruction less problematic is a little unclear. But even after 1955, the Apache continued to regularly use the lands for their Sunrise Ceremony. After sharing her recent ceremonial experience with the House Natural Resources Committee in March 2020, Naelyn Pike, a San Carlos Apache citizen and youth organizer for Apache Stronghold, rejected the notion that her people’s traditional practices exist only in the past. “I hope Congress understands that the Apache way of life is not just history but the present and future,” Pike said. “We are living and breathing. The culture and traditions are very much alive, and we pray every day that they will continue.” (You can read her full account at the bottom of this article.)

Resolution Copper’s plans for the land include a novel extraction plan for the area known as block cave mining. As described by Mine magazine, the process entails “undermining an ore body and then allowing it to collapse under its own weight, a process that opens access to deeper deposits.” The resulting mining operation would effectively replace Chi’chil Bildagoteel with a mile-wide crater following the completion of the extraction, with the potential also to pollute nearby groundwater sources.

Resolution Copper will use block cave mining to excavate ore 7,000 ft underground. The material removed would covers thousands of acres w/ toxic mine water and when closed leave behind a 2-mile wide & 1,000 ft deep crater. Oak Flat & the surrounding area would be destroyed. pic.twitter.com/jrwA0UqaEx

— Apache Stronghold (@ProtectOakFlat) January 13, 2021

This is not a hypothetical outcome—tucked halfway through the Department of Agriculture’s nearly 1,400-page Draft Environmental Impact Statement, the federal agency outright acknowledges this reality. “The Resolution Copper Project and Land Exchange has a very high potential to directly, adversely, and permanently affect numerous cultural artifacts, sacred seeps and springs, traditional ceremonial areas, resource-gathering localities, burial locations, and other places and experiences of high spiritual and other value to tribal members,” the report’s authors wrote.

At a virtual press conference held on Thursday, former San Carlos Apache tribal Chairman Wendsler Nosie, a Stronghold leader, pointed to further damage the environmental impact statement doesn’t cover: “You can’t tamper with these sacred places. We’re talking about deities; we’re talking about angels; we’re talking about where the beginning of time to the end of time will never be lost,” Nosie said. “Is this the way we are now? Is this the way we believe—to allow these places that give the gift of life to be destroyed?”

Building a coalition of tribal governments to protect Oak Flat was made difficult, said Nosie, by the dependent financial relationship many tribes have with the federal government. (As formal tribal chairman, acting as the sovereign nation’s main point of contact with the American government, he would certainly know.) That dependence, in turn, is the product of land dispossession and centuries of anti-sovereignty policies. And McCain used that: According to Nosie, McCain held up appropriations funding for the San Carlos Apache Tribe in retaliation for Nosie’s opposition to Resolution Copper.

“Behind the scenes, when I began to fight this fight, John McCain took funding away from us—that was our AIDS education,” Nosie said. “And so what I had to do as a tribal leader was build out revenue so that I could have the money to continue to outreach and educate on what AIDS was. Then, when tribes began not to really talk to me because of the issue of Oak Flat, it was because they were threatened by [the loss of] federal funding.”

McCain’s rider also subverted the National Environmental Protection Act, or NEPA. The law requires the federal government to produce a full environmental review of any proposed extractive operations, complete with a subsequent period of time to allow for a judicial review or challenge if the environmental review finds any potentially culturally or environmentally damaging effects—such as, say, a massive crater destroying sacred tribal sites. But McCain tried to weasel out of this process. Under the legislation he drew up, the moment that the Forest Service produces its aforementioned review, the land swap is required by law to occur within 60 days. As Vermont Law School professor Patrick Parenteau told High Country News, McCain essentially designed a “bastardized version” of NEPA protocols to ensure that the mining operation could not fail as long as a review is produced.

The fact that McCain’s rider passed and was signed into law makes the Apache activists pessimistic that the incoming Biden administration and Democratic congressional majorities will help them. Section 3003, after all, was signed and approved by a Democratic president and a Democratic Senate. “I’ve seen them for over 30 years, I’ve worked with Congress, I’ve spoken to them individually,” Nosie said in his press conference. “They all told me, ‘Mr. Nosie, you’re fighting the right fight, keep it up, this is wrong, but—.’ It always ends with ‘but.’”

Following the release of the Forest Service’s review on Friday, there will be nothing legally stopping Resolution Copper from forging ahead with its operations. There will undoubtedly be protests and letter-writing campaigns and grand speeches in Congress by concerned legislators. But any political opposition to the mine will be arriving six years too late.

There is still hope, of course. If enough public pressure can be built à la Standing Rock or the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, then it is possible that Rio Tinto could decide that the extraction is not worth the headache—a slim chance, though, given the copper deposits stand to be the largest remaining in North America. Resolution Copper’s proposal is just one of dozens of operations that the Trump administration’s Interior has rushed through before the Biden administration assumes control. From the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to Wyoming to Oklahoma, tribal and public lands will be at the mercy of extractive industries for years to come.

When reached for comment, Rio Tinto said that it was reviewing the Apache Stronghold lawsuit, noting that it was not named as a party in the lawsuit but that the company remains, “committed to ongoing engagement with Native American Tribes to continue shaping the project and deliver initiatives that recognize and protect cultural heritage.” The Forest Service did not respond to The New Republic’s request for comment.

Below, you can, and should, read Naelyn Pike’s full testimony.

My name is Naelyn Pike, and it is an honor today to testify before the subcommittee on behalf of the Apache youth. Thank you, Chairman Gallego and Ranking Member Cook, for convening this important hearing. I am a member of the San Carlos Apache Tribe and reside on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in rural Southeast Arizona. I am Chiricahua Apache, and my family has lived in what is now Southeastern Arizona since time immemorial.

The United States Calvary had forced my people from the land and onto the reservation in the late 1800s as prisoners of war. While we had to leave our sacred places at gunpoint, these areas still retain their spiritual, cultural, and historical connection to the Apache people. I am here today to advocate for my land, my religion, and my home on behalf of the next generation and the generations yet to come. This is Chi’chil Bildagoteel, or Oak Flat.

At least eight Apache clans and two Western Apache bands have documented history in what is today known as Oak Flat and Apache Leap. Apache people are deeply connected to our traditions and to the land that we have called home since first put here by Usen, the Creator. My people have lived, prayed, and died in Oak Flat and Tonto National Forest for centuries. My great-grandmother lived along Oak Flat’s ridge and the river which runs down from the north. Today, Apache people come to Oak Flat to participate in holy ground and sunrise dance ceremonies, to pray, to gather medicine and ceremonial items, and to seek and obtain personal peace and cleansing. I have been brought to Oak Flat my entire life. My family would come together for prayer, ceremony, to collect the acorns and berries, and to live free as Apache people once were.

I still feel that strong spiritual connection to Mother Earth, Nagosun, and to Usen at Oak Flat. It is who I am and where I am free to be Apache. It is not just the wind that hits my face or my feet hitting the ground, it is the spirits who are talking through the wind to show that they are here with us that resonates with us, and my feet waking up the earth, telling the spirits that we are still here, and we are still fighting, not ready to give up.

When I am at Oak Flat, I see what the Creator has blessed us here with and that Usen has touched this place. Oak Flat is one of the sacred areas where Apaches hold the coming-of-age ceremony for girls to make their entrance into womanhood. My sunrise dance ceremony was one of the most pivotal moments of my life and forever changed who I am and how I see this world. On the first day of my ceremony, I made the four Apache breads for the medicine man and my godparents. My godmother helped me dress into my traditional clothing and stayed with me for the entire ceremony.

During the ceremony, I had danced alongside my godmother, godfather, and partner by my side. I hit the ground hard with my cane to the drumbeat that woke the mountains, the spirits, and the Gaans, which are also known as angels, bringing them back to life. Without them, the Apache people cannot conduct our ceremonies. I awoke the Gaans and danced beside them with tears running down my face. On the third day, my partner and I danced underneath the four sacred poles. This is when I became the white-painted woman. My godfather and the Gaans painted me with the Glesh. In our creation story, the white-painted woman came out of the earth covered with the white ash from the earth’s surface.

With my face completely covered, my godmother wiped my eyes with her handkerchief. Once my eyes were opened, I looked upon this world not just as a little girl but now as an Apache woman. It is our religious right to be able to practice our ceremonies in our sacred places. If Resolution Copper proceeds with the mine at Oak Flat, it will become a giant crater. Without the land, who are we as Apache people? The land will subside, and the earth will die. How will we be able to practice our ceremonies at Oak Flat when it is destroyed? How will we harvest the acorns planted by Usen when the trees are gone? How will we collect the sacred water from the springs when it is poisoned?

The Gaan will no longer live at Oak Flat, and the destruction will irreversibly destroy the sacred Chi’chil Bildagoteel. The food and the medicine can never be replaced, nor can they ever be relocated. I am proud to be a member of the Apache Stronghold and to be standing up and making my voice heard on behalf of the Apache and other Indigenous youth.

Today, young people are standing up to protect our religion and way of life that has been under attack for far too long. Through massacre, forced removal from the land, and mandatory boarding schools, the United States has tried to silence Native voices and suppress our culture. I am here today to say that the next generation will not be silenced. I will no longer be silenced.

In the [Draft Environmental Impact Statement], the Tonto National Forest discusses the Apache way of life in the past tense, as if it is an ancient history. I hope Congress understands that the Apache way of life is not just history, but it is also present and future. Today, Congress has the opportunity to uphold the treaty and trust responsibility to the Native people and to tell a foreign mining company that our land is not for sale. My culture is not for sale. My religion is not for sale. My people and my future are not for sale. Congress has the opportunity to stand up for religious rights, for Indigenous culture, and for the environment, in the face of certain massive destruction that will be forever. The time to act is now, not only for my generation but for the generations yet to come.

Thank you.