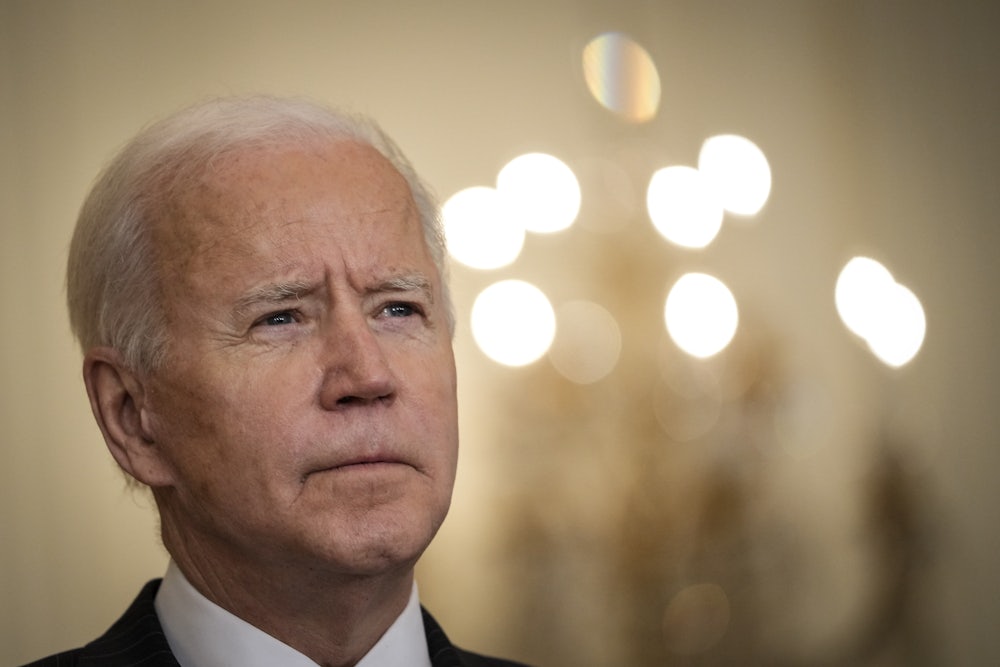

In the early days of the presidential campaign in 2019, long before the pandemic and the George Floyd protests and the insurrection at the Capitol, President Joe Biden praised two former senators, both of whom were ardent segregationists. He cited his relationships with Mississippi’s James Eastland and Georgia’s Herman Talmadge as proof of his ability to get along with his political and ideological opponents.

“At least there was some civility,” he told donors at the time. “We got things done. We didn’t agree on much of anything. We got things done. We got it finished. But today you look at the other side and you’re the enemy. Not the opposition, the enemy. We don’t talk to each other anymore.” These comments received some pushback from his opponents in the Democratic presidential primary, but they never put Biden off his stride. His overall theme of unity and bipartisanship persisted into the general election, and was a major theme of both his nominating convention and his inaugural address.

As I noted at the time, this particular version of Biden’s argument was a racial dog whistle of sorts. There was never any reason to believe GOP leaders would suddenly be willing to work with any Democrats on any major legislation by dint of Biden’s election; this Biden no doubt knew firsthand from the Obama years. I contended that Biden was quietly arguing that an older white man like himself would be the Democrats’ strongest choice to defeat a Republican Party that’s become all but consumed by grievance-based appeals to white Americans, and that his identity could be integral in reunifying the country. As it turns out, he was half-right about this.

A central aspect of Biden’s unspoken thesis—that Republicans would have a harder time opposing him because of his whiteness—so far appears to be correct. The GOP is still struggling to define him in any appreciable way for those who don’t regularly imbibe Tucker Carlson segments. His approval ratings, according to a Reuters poll released last week, currently hover around 58 percent, a far higher threshold than Trump ever achieved. If America’s vaccination rate continues to climb and the economy continues to emerge from its pandemic-induced torpor, he could also reap the benefit of a pent-up economic boom. The Federal Reserve said last week that it expects unemployment to fall to 4.5 percent in 2021 and upped its gross domestic product growth estimate for the year from 4.2 percent to 6.5 percent.

History offers us numerous caveats: Biden’s presidency is only a few months old, a lot can happen in two years, and incumbent presidents typically lose seats during midterm elections. For the moment, however, Americans still seem more worried about the economy than about the cancellation of children’s books and the gender identity of toys, and what Biden is doing about the former instead of the latter. A recent NPR poll found, for example, that 61 percent of Americans approve of how Biden is handling the pandemic. Fifty-seven percent of Americans in the survey thought the American Rescue Plan, Democrats’ name for the legislative package, was either appropriately sized or didn’t go far enough. Far fewer Americans agree with the GOP contention that it should have been narrower or more focused.

The Democrats’ major legislative effort so far, a $1.9 trillion package of stimulus measures and Covid-19 relief, made it through Congress without a single GOP vote. But it also faced feeble opposition from Republicans along the way. The Republican National Committee issued only two statements on the bill, according to Politico, and both came after it had already passed. Some GOP lawmakers have even taken to touting the bill’s relief provisions in public comments after voting against it on the floor. For a party that seemed eager to portray Biden as a radical socialist during the campaign, it has almost pulled its punches since then.

The other half of Biden’s thesis—that Republicans would be uniquely willing to work with him if he won—hasn’t been borne out. Again, Biden has a lot of his presidency still ahead. His victory over Trump, however, hasn’t sparked a moment of clarity among most GOP officeholders. A significant portion of the House Republican caucus, as well as a handful of Republican senators, actually voted to overturn Biden’s Electoral College victory in January. And after Trump incited a mob to attack the Capitol, fewer than two dozen GOP lawmakers in either chamber voted to hold him accountable for it. These were not policy-related quibbles over some mundane piece of legislation—they were votes on the future of the republic itself.

Even then, Biden still had a point. He simply does not evoke the same sense of fear or dread that Obama induced in rank-and-file conservatives. Republican lawmakers and conservative media outlets are instead trying to chase that dragon through the culture wars. When the House debated H.R. 1, the Democrats’ main election reform bill, earlier this month, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy could not help but shoehorn in something completely unrelated. “First, they outlaw Dr. Seuss, and now they want to tell us what to say,” he told his fellow lawmakers from the House floor.

It’s not clear who the “they” was in McCarthy’s example. Had Biden issued an executive order to seize the nation’s Dr. Seuss book reserves, or if Congress had passed a law to criminalize their possession, then McCarthy might have a shadow of a point. But they did not. It was the Seuss estate’s own decision to take the books out of circulation. A similar pattern played out with the brief, erroneous belief that Hasbro was transforming its Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head dolls into some sort of gender-neutral tubers. In reality, the company was just changing the overall brand name to “Potato Head,” but conservative pundits nonetheless lamented it as some sort of deeper symptom of something in America.

My colleague Alex Shephard saw these developments as a natural progression of the last decade, if not longer, of conservative politics. “The right, having largely abandoned policymaking, has settled on a political strategy that involves never-ending litigation of cultural issues,” he wrote a few weeks ago. “Desperate to make their opponents seem like Maoists, they will blow up any minor news release into a multiday controversy meant to highlight the left’s totalitarian impulses.” As if to prove Alex right, Fox News recently announced it would devote an entire special to the “cancellation” of Dr. Seuss on its streaming service Fox Nation.

Sometimes the conservative hunger for fresh sources of outrage ends in absurdity. Earlier this month, for example, Prince Harry and his wife, Meghan, gave an interview with Oprah where they discussed the psychological toll of their time in the British royal family, which included allegations of racist treatment toward the royal family’s first Black member. An American citizen’s mistreatment by the British crown should have evoked some feelings of sympathy from her countrymen. It should have resonated especially among leading conservatives who often invoke the Founding Fathers’ values, one of which was opposition to hereditary power, as forerunners of their own.

But this did not occur. “So essentially Harry and Meghan have joined Woke-o Haram and want to cancel the Royal Family for not being woke,” Erick Erickson opined on Twitter after the interview aired. “Meghan Markle is the classic American woke progressive,” added Richard Grenell, Trump’s former acting director of national intelligence. “She doesn’t want to do the work but is outraged she doesn’t get the freebies.” Joseph LaConte, a Heritage Foundation fellow, even wrote a strange op-ed for National Review in which he claimed the “radical Left” was trying to “invalidate one of the most consequential conservative institutions on the world stage.” He even gave a historically illiterate narrative of the British monarchy as a noble promoter of democratic ideals instead of a frequent obstacle to them. Later this week, the Heritage Foundation itself will hold a virtual panel on the same theme.

Some people think these narratives pose a threat to Democrats’ chances in next year’s midterms. “This burgeoning cultural revolution—and yes, I use that term knowing full well the allusion—won’t blow by like a cloud, either,” Matt Bai recently wrote for The Washington Post. “And if principle isn’t enough to persuade the White House and leading Democrats that they will need to take on the threat at some point, then self-interest ought to be. Because you can send out all the stimulus checks you want, but if 2022 rolls around and the primary image of Democrats is of a party trying to impose on the country an acceptable code of language and imagery, you will very likely lose your reed-thin majorities.”

It’s still possible that many Americans will head to the polls next November with the dangers of cancel culture foremost on their minds. It’s also theoretically possible that the defining issue of the midterm elections in 2022 will be Scottish independence or high-speed rail. Nevertheless, Biden’s bet that Republicans don’t have an effective counterstrategy to his whiteness seems to be valid, even if his larger promise of a new bipartisan era is nowhere near the mark. And if his drift away from the filibuster proves to be durable, then Republicans’ intransigence may ultimately make Biden’s presidency that much more effective.