More than four years ago, I called a constitutional law professor to ask him to explain a wave of anti-abortion legislation that blatantly violated Roe v. Wade and was therefore destined to be swiftly struck down by the courts. Lawmakers in Indiana had just proposed an outright abortion ban, establishing that life begins at conception; the Ohio state legislature had sent a six-week ban to the desk of then-Governor John Kasich, which it misleadingly and provocatively called a “heartbeat bill.”

Conservative lawmakers across the country intended to pass as many pieces of unconstitutional abortion legislation as they could and appeal them through the lower courts, the professor told me, hoping that by the time the laws reached the Supreme Court there would be a new anti-Roe majority to overturn the 1973 decision. It wasn’t a new approach. But with Donald Trump in office, a president who promised to appoint only “pro-life” justices to the Supreme Court, these legislators were newly emboldened.

At the beginning of Trump’s term, the frightening possibility that their plan might work still seemed somewhat far off. The Supreme Court had a liberal majority, and it wasn’t yet clear how many justices the new president would have the opportunity to appoint. In the meantime, conservative states were spending millions in legal fees every year to defend these bans, only to lose case after case in court. A majority of the public found the new laws off-putting, too—they considered them too extreme. And so for years—decades, even—this strategy seemed expensive and largely futile. Reporting on it sometimes felt too in the weeds for the average reader, though soon enough I was writing about it constantly, in nearly every piece about abortion laws I filed.

It seems almost quaint to think back on a time when the reasoning behind this legislation required explanation; it is now so painfully self-evident. The Supreme Court’s decision last week to take up Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban—a law that was designed to place Roe squarely in its crosshairs—is more or less proof that the anti-abortion movement’s gamble has paid off. The events that proceed from here will likely closely resemble those conservatives have long imagined: Though Roe may not be overturned outright, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett have the chance to render it virtually meaningless, to do enough damage that 22 states will make abortion illegal as soon as the ruling is handed down. The effect will be the same either way.

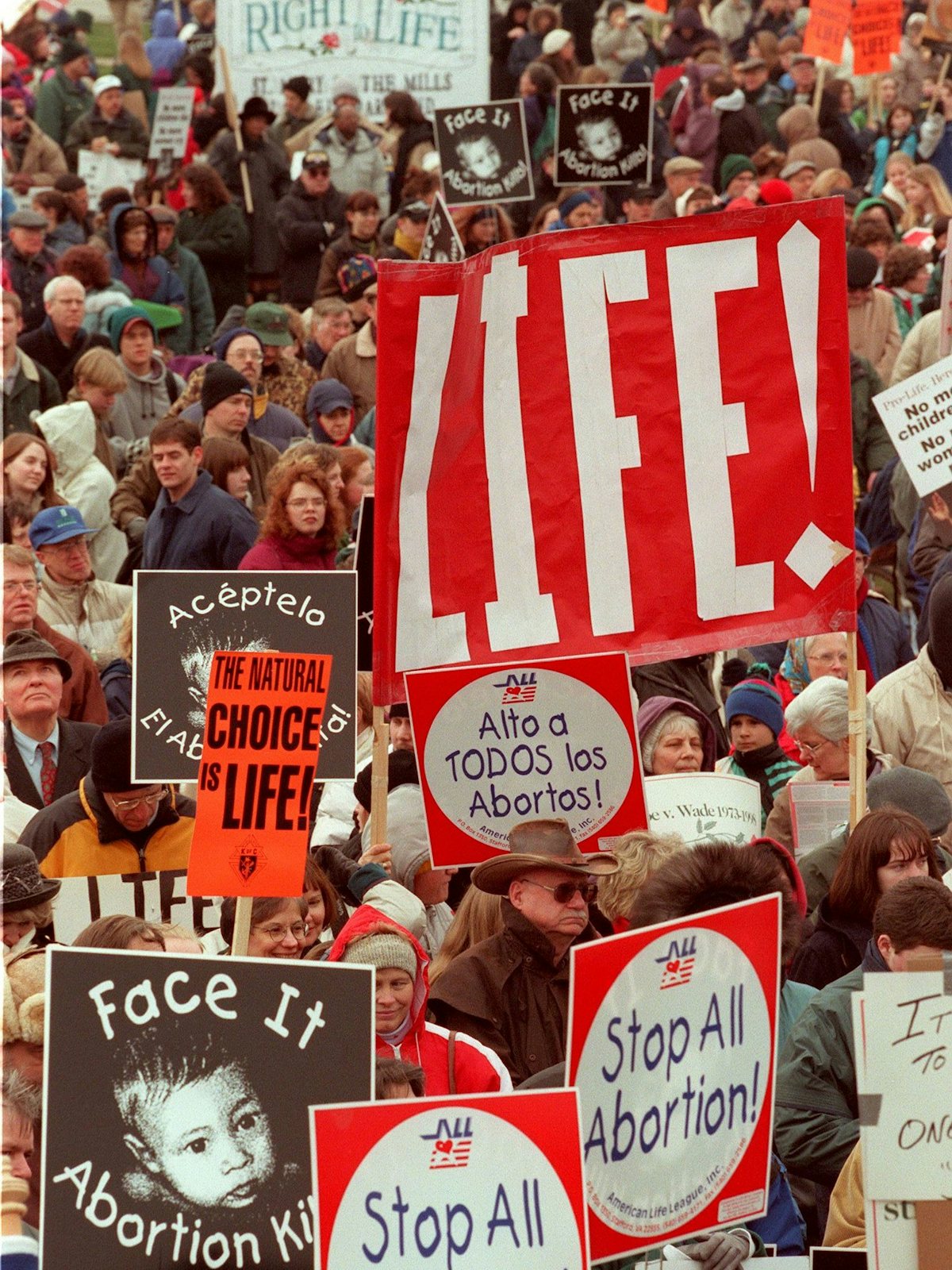

Stepping on the gas, in the end, proved to be an effective way to force abortion rights supporters into a perpetual defensive crouch and free up conservatives to bend reality to their will—all this despite the fact that a majority of people support legal abortion. Though pro-abortion advocacy groups managed to pass dozens of state laws protecting people’s right to the procedure, they’re eclipsed by hundreds of restrictions. Even in states with these proactive policies on the books, people struggle to obtain the procedure due to long-standing limits on the government’s ability to subsidize abortion care for low-income patients. The anti-abortion movement spent decades debating the merits of going after Roe full force versus dismantling it piece by piece. Yet here we are—right where it wanted.

To understand this moment, it’s necessary to go back to 1992, when the Supreme Court heard Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the ruling that remade abortion politics in the United States. The case addressed the 1989 Abortion Control Act, omnibus legislation out of Pennsylvania that included spousal notification and parental consent requirements, a 24-hour waiting period, and a mandate that clinics report to the state with extensive information about patients whom they provide with abortion care. “Whether our Constitution endows government with the power to force a woman to continue or end a pregnancy against her will is the central question in this case,” Kathryn Kolbert, who argued Casey before the court, said in her opening remarks. To almost everyone involved, it seemed like a given that the Supreme Court would use the law to overturn Roe—there were only two justices on the court who were thought to be interested in upholding the decision. Instead, five of the justices opted to reaffirm the abortion rights ruling.

At first glance, this outcome looked like a clear victory for abortion rights supporters and an obvious defeat for their opponents; but in reality, both camps walked away believing they’d been defeated. Stephen Freind, the architect of the legislation and the self-described “point man” at the time for the attacks on abortion coming from state legislatures, felt he had let down his movement. On the Planned Parenthood side, advocates noticed that, while still technically intact, Roe had been significantly weakened: The court had established the “undue burden” test, which stated that abortion restrictions would only be deemed unconstitutional if they had the “purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path” of someone trying to obtain the procedure.

In this sense, abortion rights supporters were simply more correct in feeling that they had lost. This looser interpretation of Roe has been cited in two major Supreme Court cases since, defending the ruling. But it also became the foundation for a conservative strategy that has been in the works since at least 1989, when the court failed to repeal Roe in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services. “Because of … constitutional constraints, an incremental or gradualist strategy has been pursued to overturn Roe v. Wade through constitutional litigation in the courts,” Clarke Forsythe, senior counsel for Americans United for Life, wrote in a 1991 law paper. “The strategy entails the passage of carefully drafted state abortion legislation.”

The words “undue burden” were accepted as a challenge by anti-abortion lawmakers, an inducement to pass the most restrictive laws possible and disingenuously argue that the laws did not prevent someone from getting an abortion. (This, of course, was false.) The strategy heavily relied on template legislation that allowed anti-abortion lawmakers in different states to pass identical bills; legislators need only fill in the blanks before introducing the bills to their colleagues. These included: waiting period requirements, clinic “safety” mandates, 20-week bans, and six-week “heartbeat bills,” the last of which is perhaps the best example of anti-abortion activists’ success at pushing their agenda.

The legislation is the invention of a woman named Janet Porter, the leader of the group Faith2Action, who was the first to come up with the idea of using “fetal heartbeat” language in abortion legislation. She succeeded at getting the first state lawmaker to sponsor her signature bill in 2011, in Ohio. That year, the number of abortion and family planning restrictions skyrocketed, when at least 92 were enacted across the U.S., the highest number of restrictions the country had seen at that point. Many of them were six-week bans or, riffing on the rhetoric Porter had introduced, laws requiring pregnant people seeking abortions first to listen to the supposed heartbeat on an ultrasound machine. (An embryo does not even have a heart at six weeks, though the science hardly matters. These bills are engineered to incite extreme emotion—sympathy for an embryo and abhorrence for people seeking abortions. It’s a strategy that works.)

At times, the six-week bans have represented a division within the anti-abortion movement. Some conservatives saw them as being too overt in their violation of Roe and therefore a betrayal of the incrementalist approach the movement’s leaders had honed over decades. In 2011, after the first “heartbeat” ban was introduced in Ohio, The New York Times covered it as causing a “split” among conservatives: “Now many activists and evangelical Christian groups are pressing for an all-out legal assault on Roe. v. Wade in the hope—others call it a reckless dream—that the Supreme Court is ready to consider a radical change in the ruling.” The divide persisted for years: In 2016 and 2018, Kasich, a staunchly anti-abortion Republican, ultimately vetoed the six-week bans sent to his desk; both times, he called them them “contrary” to the law under Roe.

When state legislatures first began introducing the bans, many abortion rights supporters were also dismissive of them: “It was such a complete dog and pony show,” Stephanie Craddock Sherwood, a former Planned Parenthood organizer, recalled in a 2019 interview with The Nation. “I was like, ‘There’s no way this will ever pass, because it’s so ridiculous.’” And it has been conventional wisdom—among both pro- and anti-abortion activists—that if the Supreme Court took up an abortion case with the intention of overturning Roe, its content would have to be more understated. Up until last week, reproductive rights advocates and experts had speculated that justices might pick a law having to do with abortions later in pregnancy or a Down syndrome abortion law, which exploits the principles of the disability rights movement to restrict the procedure.

Porter, though, maintained faith in the strategy. In 2012, she described “heartbeat” legislation as “crafted with the Supreme Court in mind.” She accused her critics, particularly those in the anti-abortion movement, of a lack of vision and ambition. “Those who say the bill is ‘unconstitutional’ fail to realize that it is Roe v. Wade that is unconstitutional,” she wrote, “and the only way to reverse it is with a challenge.”

In hindsight, it’s easy to see how these two organizing styles—one deceptive and gradual, the other brazen and accelerationist—are not oppositional but in fact twinned. The former chipped away at Roe little by little, making the right to abortion theoretical for people who had to wait 72 hours to get one or drive hundreds of miles to the nearest clinic. The latter made those barriers seem reasonable when compared to the extreme bans anti-abortion lawmakers were simultaneously introducing. This strategy proved that eventually anything could be normalized with enough persistence.

In the short term, the arcane laws have most altered the landscape of abortion access in the U.S., bringing restrictions that weren’t outrageous enough to gain widespread attention. (It can be difficult, for example, to convey why requiring clinics to have hospital admitting privileges is so devastating to access.) But the more audacious ones succeeded in forcing the national conversation around abortion to happen on the anti-abortion movement’s terms. The gestational limits at the core of these pieces of legislation—20 weeks, 15, eight, six—are largely arbitrary, yet reproductive health experts have no choice but to invoke them in order to explain why they’re meaningless and cruel. So-called “born alive” bills are based on a false premise that there is a high percentage of botched abortions, resulting in people delivering infants who need protection against infanticide (which is already illegal). While it isn’t hard to prove that these laws weren’t based in science, they create powerful narratives, and there is a dulling effect to introducing the same laws over and over. Even those who are outraged by restrictions on abortion might stop paying attention, particularly when news outlets announce that the latest ban is the “most extreme yet” every few weeks. This, too, is a way the anti-abortion movement has goaded people into dishonesty—they are all extreme.

And in truth, the flagrantly unconstitutional legislation has had short-term impacts, as well. Though the laws are blocked from going into effect the moment they pass, many people end up believing abortion has been made illegal in their state. In the aftermath of a wave of six-week abortion bans in 2019—all of which were later struck down—clinics received calls from patients wondering if they could still come in for their appointments or panicked that they missed the legal limit to have the procedure. Abortion rights groups in hostile states, like Texas, are often forced to spend considerable time and resources on messaging that clarifies the simple fact that abortion is still legal, making it more difficult to focus on long-term strategies that could not just protect but expand abortion access.

This is why it would be a mistake to think of the struck-down laws leading up to Mississippi’s as throwaways, failed attempts at realizing the anti-abortion movement’s ultimate goal. Look more closely, and you can see a million cuts. Perhaps it is also why many of the initial critics of the accelerationist approach came to accept it. The bans did not need to go into effect to do damage; they could make it more difficult for people to get abortions with the idea of them alone. (Not to mention that they sometimes included hidden anti-abortion riders, which were often allowed to go into effect even when the primary law being proposed was thrown out.) In December 2018, after previously rejecting the strategy of the six-week bans, Ohio Right to Life announced it was “time to embrace the heartbeat bill as the next incremental approach to ending abortion in Ohio.”

It was never a given that this approach would succeed. The Supreme Court punted its decision on whether to hear Mississippi’s case for several months before deciding to take it up. Despite the traction abortion bans have gained over the last decade, it was still a surprise to many to hear that justices would likely use one to dismantle Roe. Abortion rights advocates thought the end to federal abortion rights—if it ever came—would be more subtle. “I think the most obvious strategy, if you are an abortion opponent, is to gut abortion rights without gutting abortion precedents,” Mary Zeigler, author of Abortion and the Law in America: Roe v. Wade to the Present, told The New Yorker last year. “In other words, to say that women still have a right to an abortion but to functionally eliminate access to abortion. That is much more likely.”

But there is no longer any need for subtlety. That the Supreme Court has even agreed to hear the Mississippi law is a vindication of the anti-abortion movement’s decision to seize political power with brute force.

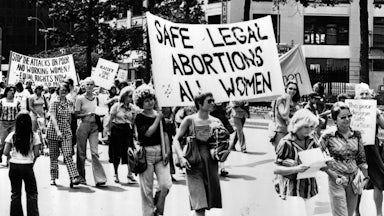

It’s frustrating to lose to an opponent like this. Kolbert, the lawyer who represented Planned Parenthood at the Supreme Court in 1992, believes she won the case, improbably, because of the public outrage and mass protests that surrounded it. Planned Parenthood v. Casey dealt with more arcane legislation, but abortion rights organizers were able to make the stakes clear—it was a challenge to Roe. This is not likely to work a second time. Still, over the last several years, a more robust grassroots abortion movement has begun to emerge, acknowledging that access has never been guaranteed by Supreme Court rulings. These organizers are, as Katie McDonough wrote for The New Republic last January, “confrontational, nimble, collaborative, [and] deeply moral.” They know, for example, how easy it can be to hide abortion pills in a package in the mail.

Whatever happens to Roe, their work will have to continue: driving people across state lines, helping people buy pills online, and passing around instructions for how to perform an at-home abortion. They are a necessary counterbalance to the anti-abortion activists now responsible for one of the most consequential cases before the Supreme Court: They understand what exists beyond the law. They can already see a horizon beyond the fall of Roe v. Wade, and they are not afraid; perhaps we can fix our eyes on that, too.