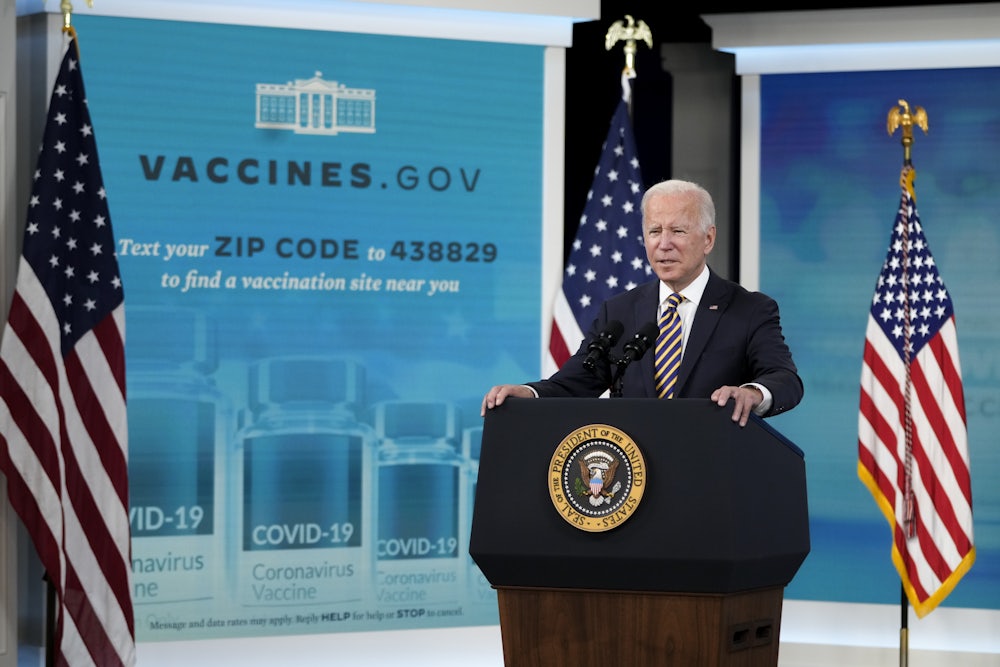

The Biden administration unveiled its emergency rule for Covid-19 protections for large companies on Thursday, starting a two-month clock for firms that employ roughly two-thirds of the American workforce to adopt mandatory vaccination policies or take alternative steps. The new Occupational Safety and Health Administration rule comes two months after President Joe Biden announced a series of measures that he said would help swiftly end the pandemic.

“Vaccination requirements are good for the economy,” Biden said in a statement on Thursday, avoiding the word mandate to describe the OSHA rule. “They not only increase vaccination rates, but they help send people back to work—as many as five million American workers. They make our economy more resilient in the face of Covid and keep our businesses open.” The president said that while he would have preferred to avoid the rule, “too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good.”

Republicans on Capitol Hill responded with fury at the announcement. A group of GOP lawmakers said they would try to use the Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to block new federal regulations in some circumstances, to nix the OSHA rule. Other members expressed support for a bill that would abolish OSHA altogether because of the announced rule. Florida state lawmaker Anthony Sabatini even urged “every Republican state” to nullify the federal rule and arrest OSHA officials who try to enforce it—a proposal that would violate the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause and spark a constitutional crisis.

In nearly every statement other than Biden’s, and in many news reports on the matter, the OSHA rule was described as a “vaccine mandate.” But this is not actually correct. The new rule is better understood as a testing mandate with a vaccine exception—and that distinction could be crucial as it works its way through courts of law and public opinion.

What did OSHA actually do? The agency unveiled what is known as an “emergency temporary standard,” or ETS, on Covid-19 vaccination and testing for most companies with more than 100 workers. The ETS is roughly 490 pages long, with fewer than two dozen pages dedicated to the rule itself and the rest devoted to its justification. It requires eligible companies to do a few things to make vaccinations easier for their employees to obtain: provide paid time off so workers can get vaccinated and recover from any side effects, maintain lists of which workers have already been vaccinated, establish a notification system for workers who test positive, and other administrative requirements. It also generally requires employers to tell unvaccinated employees to wear masks.

What the agency will not be doing is forcing anyone to get a vaccine—at least, not directly. According to OSHA, the ETS requires companies to “develop, implement, and enforce a mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy.” But—and this is a big but—there is a pretty clear way around this. The affected companies can forgo a vaccine mandate policy if they “instead establish, implement, and enforce a policy allowing employees to elect either to get vaccinated or to undergo weekly COVID-19 testing and wear a face covering at the workplace.”

Imagine that you’re the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. OSHA has effectively presented you with two choices. Your first option is to order your workers to get vaccinated to comply with OSHA’s requirements. Your second option is to order your unvaccinated workers to get regular testing and wear face coverings while on the job. Though the Biden administration is framing the vaccine-mandate part of the ETS as the default and the testing-and-masking part as an exemption to it, there’s no reason it can’t be the other way around.

That might sound like a meaningless distinction for some workers who may now be compelled to get vaccinated either way. But there’s a difference between a mandate imposed by the government and one imposed by a company. In the actual ETS, OSHA said that an employer-based vaccine mandate, as opposed to one from OSHA itself, “will be the most effective approach for increasing the vaccination rate of its employees and ensuring that they have the best protection available against the worst consequences of a COVID-19 infection.”

And while OSHA claimed in the rule that it “may well have the authority to impose a vaccination mandate” itself, the agency said it instead decided against “pursuing [a] strict vaccination requirement” in favor of a rule that would “strongly encourage” vaccines. “OSHA’s traditional practice when including medical procedures, such as medical surveillance testing and vaccinations, in its health standards has been to require the employer to make the medical procedure available to employees, and has viewed mandating those procedures as a measure to avoid if possible,” the agency explained.

OSHA outlined a few benefits of mandating vaccines for employers themselves. “Most obviously, employers with a mandatory vaccination policy will enjoy a dramatically reduced risk that their employees will become severely ill or die of a COVID-19 infection,” the agency said. Of course, if companies always cared so deeply about their workers’ health and welfare, OSHA wouldn’t exist. So it also discussed the cost-benefit problems of having a largely unvaccinated workforce, which is more likely to have higher rates of worker absences for illness.

The real benefit for employers who issue a vaccine mandate is saved for last in OSHA’s explanation. “Additionally, only employers who decline to implement a mandatory vaccination program are required by the rule to assume the administrative burden necessary to ensure that unvaccinated workers are regularly tested for COVID-19 and wear face coverings when they work near others,” the agency noted. In other words, under the new rule, it may be cheaper for large companies to tell workers to get the shot rather than pay for thousands of weekly Covid-19 tests.

There are some exceptions, of course. The rule does not apply to workers who telecommute or otherwise don’t work around other people, where there is no risk of workplace transmission, as well as workers who work entirely outdoors, where the transmission risk is dramatically lower. Companies with fewer than 100 workers are also exempt, OSHA said, because they are less able to shoulder the administrative burden relative to the public health benefits. The OSHA rule also works in concert with existing bona fide vaccine mandates issued by the Biden administration: It recently issued vaccine mandates for federal employees, for workers at companies with government contracts, and for the entire U.S. military.

As with virtually every other aspect of American life, litigation over the OSHA rule is inevitable. One question for courts to resolve will be whether Covid-19 counts as a “grave danger” under the law that allows OSHA to issue an ETS in the first place. Another one that will likely attract the courts’ attention is whether workers can seek religious exemptions from company-imposed vaccine mandates, especially when enacted under the aegis of an OSHA rule. Conservative legal groups have already filed multiple lawsuits against the Biden administration to block the rule on more general grounds. The Supreme Court’s conservative majority, which is generally wary of federal regulatory power, may be more inclined to uphold a vaccine mandate that, well, doesn’t actually mandate vaccines for anyone.

So why doesn’t the Biden administration just call it a testing mandate or something like that? The White House’s use of the phrase “vaccine requirement” suggests that it’s trying not to use the phrase “vaccine mandate,” while also trying not to say, “It’s not a vaccine mandate.” Perhaps the most likely answer is that the administration wants Americans to think there’s a massive federal vaccine mandate without actually risking the legal or political consequences of imposing one. It’s more practical—and perhaps more quintessentially American—for the government to outsource a coercive policy goal to the private sector instead of doing something itself.

Indeed, large companies like Google, Ford Motors (no relation), and Tyson Foods have already mandated vaccines for their workers. Other employers who might want to issue mandates can now say, “Hey, don’t blame us, we’re just trying to comply with OSHA here.” To make things easier, the OSHA rule also supersedes state and local bans on vaccine and mask mandates in Republican-led parts of the country. If the courts allow it to take effect, the rule may yet prompt enough companies and enough workers to get the shot to help end the pandemic for good. Just don’t call it a vaccine mandate.