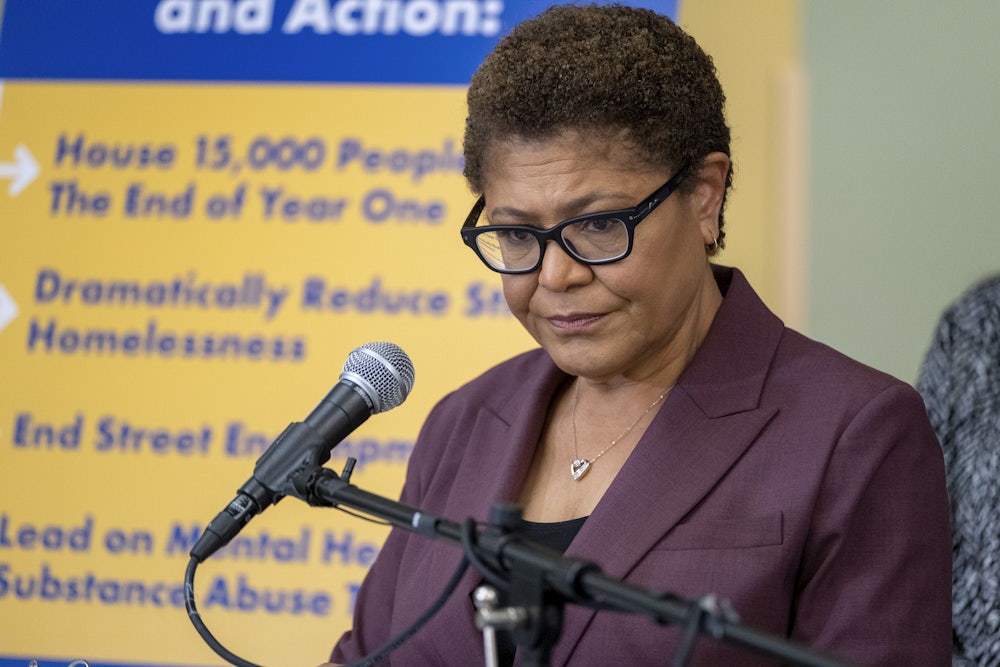

As she was launching her campaign to be the next mayor of Los Angeles, Congresswoman Karen Bass met with activists from the Los Angeles chapter of Black Lives Matter. Even though some present had been friends with Bass for decades, as Bass explained her public safety plan it became clear to all parties that they would not be working together.

“We tried to be candid with her,” said Greg Akili, one of the leaders of Black Lives Matter–Los Angeles, who attended the meeting. “We each left knowing that if she went down that road, she was not going to have our support.”

Bass’s run for mayor of Los Angeles should excite progressives in the city: Bass, a former nurse raised by a mailman and a salon owner in West L.A., is a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, a former Congressional Black Caucus chair, and a Medicare for All supporter. But returning to Los Angeles from Capitol Hill, she finds herself caught between law and order–minded election opponents and an organized left that refuses to let her expand policing while maintaining her progressive reputation.

The congresswoman has fallen out with the city’s left wing in a series of high-profile incidents. At a mayoral debate at Loyola Marymount University, protesters disrupted proceedings six times to criticize candidates’ unity on police investment and homelessness criminalization. “Karen, stop being a Karen!” Jason Reedy yelled at Bass, who compared protesters at the debate with January 6 rioters, as part of a pattern of declining American discourse. “It was disgusting,” Reedy later said. “In my youth, I was proud to say I was part of the Democratic Party.”

Bass’s public safety plan calls for the deployment of at least 250 new officers to return the force to its authorized capacity of 9,700 (though as of April 5, the Los Angeles Police Department is 310 officers short of authorized capacity). Her plan would also invest in community policing, increase foot and bike patrols where requested, “partner” with business improvement districts, expand LAPD staff, and lend senior lead officers their own budgets to use at their discretion. Her crime prevention plan, meanwhile, states that “Los Angeles cannot arrest its way out of crime” and seeks to address crime through community investment, Bass told The New Republic. Bass wants to start an Office of Community Safety “completely separate from law enforcement” that would oversee programs like L.A.’s Gang Reduction and Youth Development initiative, which launched as part of the Los Angeles mayoral office in 2007.

Currently, Los Angeles allocates more than $3 billion to its police force, but BLM organizers won an unprecedented $150 million cut in 2020. According to BLM-LA’s Melina Abdullah, who calls Bass a longtime friend, Bass’s public safety plan harms the movement while guarding against the right. With BLM co-founder Patrisse Cullors, Abdullah penned an op-ed to Bass, hoping to “call in” Bass rather than cancel or call her out.

Bass’s mayoral run may be the best example in the country of the Democratic Party’s ambivalent relationship to the Black Lives Matter movement that captured the hearts of many Democrats in 2020. Not two years ago, as protesters clashed with police officers in the streets of Los Angeles, Bass authored the Democratic response to the George Floyd murder. The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act would have banned chokeholds, ended qualified immunity law protecting cops from lawsuits, and banned no-knock warrants in drug cases—while also funding police departments—but it never passed the Senate. Even in the midst of the uprisings, Bass said that “Defund the Police” was “probably one of the worst slogans ever.”

Her public safety plan tries to balance reform initiatives with defund backlash, even promising different levels of policing on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis. “Some communities want to see increased visibility from police patrols, while other neighborhoods find more value in proven model programs that build trust and cooperation between community members and law enforcement,” her plan says. “It’s time to tailor crime response to the needs of individual communities.” Each neighborhood’s relative desire for cops would be assessed in a series of livestreams conducted with the Mayor’s Office during the first year of her term.

While insisting the city must not repeat the 1980s and 1990s, Bass has also issued statements that feel like quotations from that era. In an interview with Bloomberg published under the headline “LA Mayor Hopeful Karen Bass Vows Tough Stance on Crime,” Bass said, “People around the city do not feel safe. There is a feeling of fear in the city. It’s very reminiscent to me of where the city was in the ’80s and the ’90s.” The quote echoed a statement from her opponent Rick Caruso at a debate at the University of Southern California. Caruso is now running even with Bass, ahead of third-place candidate Kevin de Leon and nine other contenders. “Everybody in this city, at every corner of the city—no matter where you live, what your background is—is scared to walk out their doors,” he said, later claiming that crime levels today are the worst in the history of Los Angeles, though the current homicide rate is 85 percent lower than in 1992. Caruso wants to expand the LAPD to 11,000 officers.

Bass witnessed the advent of mass incarceration firsthand in Los Angeles as a nurse in the 1980s and then as the founder of the nonprofit Community Coalition in the ’90s. Retiring from Congress at 68, she finds herself in the position of defending against a second carceral wave. “We waged campaigns against every single [mass incarceration law], and we obviously lost,” she said in an interview. “Now I am concerned that progressives are not really responding to what happens the day the bank gets robbed. And I think if we don’t have an answer for the day the bank gets robbed, we are handing it over to the right.”

What happens when the bank gets robbed? “The bank robber has to be arrested, come on,” Bass said. “And by the way, if I’m wrong, please tell me what the answer is. Please tell me a progressive answer for when the bank is robbed.”

Bass must also weigh in on homelessness criminalization, an issue rocking local politicians. Last summer, the City Council reinstated city ordinance 41.18, which allows councilmembers to sweep encampments at their discretion, and Bass’s opponents are running on platforms promising to end homelessness with brute force. Councilmember Joe Buscaino’s No Excuses Homelessness Plan “bans camping citywide,” while Rick Caruso, like California Governor Gavin Newsom, wants to clear encampments and place unhoused people into conservatorships. (“It is truly a travesty that someone as cognizant and aware as Britney Spears can be in a conservatorship, but a homeless person slowly killing themselves with a brutal meth addiction can’t be compelled into treatment,” Caruso’s policy says.)

Bass insists that she rejects encampment sweeps. She wants to discard congregate shelter for single-occupancy options, including redesigning tiny homes to be much larger and even include cooking spaces—moves the left would cheer. But Bass also stated her support for the “intent” and “sentiment” of 41.18, especially when encampments block doorways and public access, a common refrain from Los Angeles politicians who frequently cite disability access when leveling tents, destroying property and medicine, and scattering the unhoused across the county where their service providers cannot find them. When the Los Angeles Daily News asked Bass if she supported a citywide camping ban if Los Angeles met shelter requirements mandated by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, Bass said, “There are some things you just don’t do outside, and sleeping is one of them.”

Her homelessness policy also promises an “end to street encampments” during her term—a goal she told The New Republic she would reach by “getting people housed”—but activists, overly familiar with politicians promising they can end homelessness, worry this will mean enforcement. “When she uses phrases like ‘end street encampments,’ that’s extremely alarming,” said Jane Nguyen, co-founder of homelessness outreach group Ktown for All. Activists shouted down mayoral candidates at a recent homelessness debate, accusing them of wanting to sweep the unhoused. Bass, with the rest of the field, packed up her things and left early.

Still, as crime panic increasingly occupies the mainstream of Los Angeles politics, activists concede that Bass may be their best bet to defeat Caruso. It just seems that they’ll have to influence her from outside her Cabinet.