In January, Roe v. Wade will celebrate its fiftieth anniversary. In the meantime, as the United States Supreme Court deliberates over whether to support or disarm the 1973 ruling, the nation watches and waits. I am the former attorney for Norma McCorvey, the plaintiff in the case, better known as Jane Roe, and I have profound concerns—not for history, for the future. My co-counsel Sarah Weddington and I forged for American women the right to privacy, not just in abortion law, but in all parts of one’s personal life. A better sense of what is at stake today can perhaps be gleaned from the legal journey we took to establish that right.

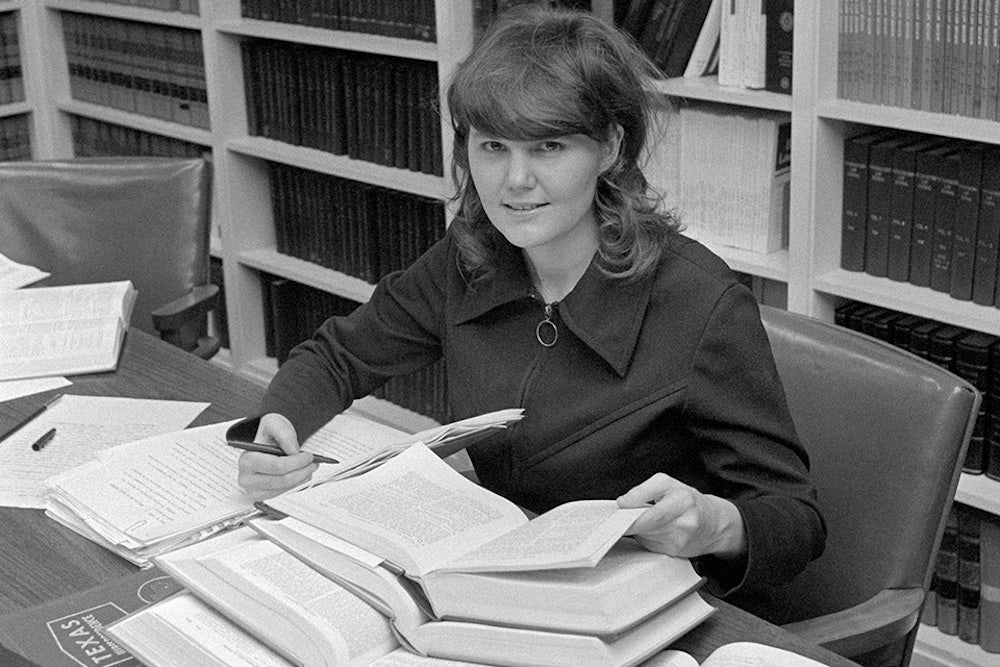

I graduated from the University of Texas School of Law in May 1968, but I began researching and writing a challenge to Texas’s abortion laws a full year before. Following graduation, I spent many nights of intense study in the Southern Methodist University law school library, where I initially focused on what did not work in previous challenges to various abortion restrictions around the country. Those challenges had all failed. A good lawyer does not use failed arguments to win a good case.

The most pertinent case I reviewed was 1969’s People v. Belous, in which Dr. Leon P. Belous, a well-respected physician and a supporter of abortion rights, was arrested for actions related to his 35-year history of performing abortions in California. Belous’s attorneys appealed the district court’s support of anti-abortion laws to the state Supreme Court, citing an earlier case, 1964’s Griswold v. Connecticut, which protected a woman’s privacy and argued that personal autonomy in childbearing was hers alone to exercise. On September 5, 1969, to the shock of many people across the country, the California Supreme Court overturned the Belous guilty verdict by a vote of 4–3, asserting that women have privacy, a right to follow their own convictions about reproduction, and liberty in matters related to marriage, family, and sex.

To enable women to make their own decisions concerning their own bodies, and to overturn Texas’s overreaching laws and their burdensome and unnecessary control, my plans had to be precise. This issue of “privacy” struck me as offering the best grounds on which to successfully challenge Texas abortion laws. Many people do not know that neither the U.S. Constitution nor any of the amendments actually protects citizens with a “right to privacy,” verbatim. But any case I made, I knew, would need to center on it.

I first met Norma McCorvey in my law office at Palmer and Palmer Law in late November 1969, after my lifelong friend and fellow attorney, Henry McCluskey, called to say he had an adoption client who preferred an abortion. He knew I had been researching and writing to develop a challenge to Texas’s abortion laws. He also knew that, to have standing, we would need a woman pregnant and not wanting to be. I told Norma about my class-action plan to challenge Texas law, and Henry encouraged her by telling her I had been working for some time to help women in her situation. I explained that representing her, as part of a class of Texas women, would cost her nothing, as I would be working as a pro bono attorney. I explained she would be helping women like herself who were pregnant, but who didn’t want to carry their pregnancy to full term.

A few days after meeting with Norma in my office, I reached out to my law school peer, Sarah Weddington, who lived in Austin. I had—for the most part—finished writing the case that would be filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, and would advance little changed in the version that was presented to the Supreme Court. Sarah had impeccable skills in oral arguing. When I asked if she would like to join me in the fight, she quickly agreed to join the team. Something I did not discover until later was that Sarah and her husband, Ron, had already experienced Texas’s abortion law firsthand. Sarah had become pregnant during our last year in law school at UT Austin, and she and Ron traveled to Mexico so she could have an abortion outside Texas borders.

In January, I asked Norma to join Sarah and me for an informal get-together over pizza. We agreed on Columbo’s on Greenville Avenue, near the iconic Dr Pepper National Headquarters. Wearing casual clothing, Norma met us in a corner booth covered with a red-check tablecloth. We were dressed in business suits. As we dined on pizza and beer, we explained to her the plan for a class-action abortion case.

During the conversation, Norma focused on Sarah. She connected with my lawyer-teacher friend easily, and I saw no need to interfere. As I later learned, Norma had experienced a very difficult and challenging life. She had already given birth to two children, both of whom had been adopted out. She did not wish to repeat the experience.

Barely two months later, on March 3, 1970, I filed the case under Roe v. Wade for a $15 fee in the Clerk’s Office of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, and then, for a second $15 filing fee, immediately refiled the case under Doe v. Wade for another couple we’d found, “John and Mary Doe,” in case the judiciary preferred a male plaintiff. (They did not.)

The hearing took place on May 22, 1970. Less than a month later, the three-panel judge, composed of William M. Taylor Jr., Irving L. Goldberg, and Sarah T. Hughes, announced a unanimous decision in favor of plaintiff Jane Roe. Texas women had won, as Norma did, but the news was personally disheartening: Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade declared that, despite the loss, he would continue to arrest any doctor who assisted in providing abortions in Texas. Norma and all Texas women were faced with a two-and-a-half–year wait until the Supreme Court took up the case. Norma’s baby was born on June 2, 1970. She never received an abortion.

Nearly 50 years after the most polarizing court case in more than 230 years of judicial history, where are we? Roe v. Wade established a federal standard. Unless the Supreme Court knocks down the oppressive state “heartbeat” laws that make it almost impossible to obtain an abortion, it appears that the court’s decision may revert all laws on abortion back to the states to control. As a result, after half a century of the freedom to exercise their constitutional right to privacy, women who desire an abortion will need to travel to abortion-friendly states, trips that will cost time, money, and emotional turmoil—trips that some will not be able to make. But perhaps most important, the loss of the right to privacy and the ability of American women to make their own decisions about pregnancy signifies a loss of dignity. It is a giant step backward in American history.

In Roe v. Wade, Warren Burger, the fifteenth chief justice of the Supreme Court, recognized not just the right to privacy in reproductive decisions, but the whole of what the court called “zones of privacy.” Will the Supreme Court’s action on abortion mark the end of personal decision-making protected by this right? Will it revive what the court once deemed the overreaching, unnecessary, and excessively burdensome control of citizens? What other freedoms will Americans see retracted if the right to privacy ends in America? We must think fast and deeply about what it means to undermine this and any right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution—before it’s too late.