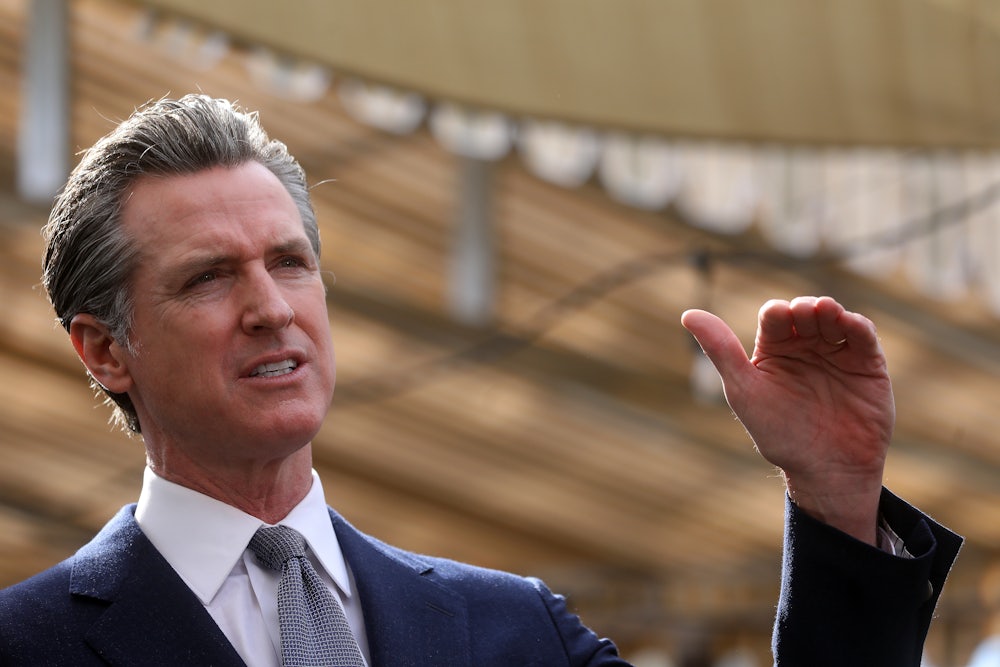

Last week, California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill that had sailed through a legislature controlled by a supermajority of his fellow Democrats. He then got immediately to work lying his ass off about why he had rebuked his colleagues in this fashion: “While I have long supported the cutting edge of harm reduction strategies,” he wrote, “I am acutely concerned about the operations of safe injection sites without strong, engaged local leadership and well-documented, vetted, and thoughtful operation and sustainability plans.” At issue was Senate Bill 57, which would have created legally sanctioned overdose-prevention centers in three cities, the better to ameliorate a growing public health emergency in these municipalities. Newsom, however, bailed on the much-ballyhooed plan, saying that the facilities “could induce a world of unintended consequences.… If done without a strong plan, they could work against [the purpose of improving health and safety].”

As Newsom well knows, that’s a load of fiddle-faddle. His concerns about the lack of appropriate stewardship and hasty planning are insulting: The bill was co-sponsored by a broad swath of harm-reduction organizations, including the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, the Drug Policy Alliance, the National Harm Reduction Coalition, HealthRIGHT 360, and others, who collaborated on the spiked pilot project’s specifics for over a year and repeatedly coordinated with the governor’s office throughout the process. Just how far along was that process, exactly? Far enough that the city of San Francisco had already purchased and designated specific buildings as future supervised-consumption sites.

Moreover, several of those aforementioned groups already run large-scale opioid-replacement treatment programs, needle exchanges, and Narcan trainings throughout their communities. It’s hardly a surprise, then, that many local officials have denounced Newsom’s veto and have vowed to go forward with their already laid plans. And with some 200 such centers operating successfully across the world, there’s not particularly persuasive evidence that they diminish health and safety. If you don’t believe me, take it from the 2018 version of Gavin Newsom, who described himself as “very very open” to the idea while campaigning for governor.

Ahh, but that was the Gavin Newsom from before he’d spent a few years helming the country’s biggest state, trounced a right-wing nutcase in a high-profile recall election, and read recent poll results suggesting he’s a solid contender to fill an imminent post-Biden vacuum. In short, Gavin Newsom vetoed a widely supported and humane bill deeply grounded in evidence because he wants to be president and has made the calculation that if he wants to move up in a rich Democratic Party that’s traditionally screwed over the kind of people served by overdose-prevention centers, he’d better put on a good show.

That anyone—let alone a Democratic leader who leaned heavily on his quasi-progressive bona fides while campaigning—would undermine such promising efforts to save lives, at a time when more than 100,000 people die of overdoses each year, is a disgrace. For decades now, the so-called “war on drugs” has engineered a degree of human suffering that hardly could have been exceeded were that itself the goal: Mass incarceration, poverty, homelessness, and abuse have all been exacerbated to varying degrees by the dogged insistence on using the criminal justice system to adjudicate drug use. Only in recent years has noticeable opposition to this paradigm broken into the mainstream; even so, the status quo has proven to be infuriatingly durable.

Harm reduction offers an alternate analysis: The personal and societal damage wrought by drug use is better tackled on its own terms than through the criminal justice system, which essentially strives to reduce danger as an aspirational downstream consequence of abolition backed by rigorous state enforcement. We have a dizzying amount of evidence that it doesn’t work: It took us just over a decade to realize that about the prohibition of alcohol, which not only drove crime of the familiar bootlegging variety but also caused deaths from unregulated moonshine.

We’ve come to accept moderate recreational alcohol use as mundane and morally neutral; there’s no reason not to approach drugs the same way. For a harm-reduction proponent, the principal problem with opioids that needs solving is that millions of disproportionately young people are getting sick and dying from using them. These are preventable tragedies with straightforward solutions. Since the 1980s, clean syringe distribution programs have significantly reduced rates of HIV and hepatitis C infection among drug users; timely administration of naloxone can reverse nearly every otherwise fatal overdose. But access to these resources is piecemeal and too often individualized. Getting them to everyone in need requires supportive infrastructure to serve the needs of people who use drugs and connect them to testing and care. Overdose-prevention centers are uniquely equipped to accomplish this task.

Newsom’s veto, though, amounted to a rejection of that analysis. To the people to whom he is trying to pander, the problem with drugs is not that they kill people who do drugs. Rather, it’s that they inconvenience and irritate people who don’t use them. To dazzlingly rich property owners—and potential political donors—in cities striving to welcome safe injection sites, sanctioned drug injection raises specters of disorder, littered paraphernalia, panhandling ne’er-do-wells, and petty crime, which makes them more than happy to delude themselves into suggesting lives can best be saved convolutedly through legislation and incentives instead of by making deadly things less deadly.

Newsom is hardly the first liberal public official to prioritize elite lifestyle and aesthetic preferences over the dignity of the poor. This is especially true when it comes to crime. And it’s no coincidence that this veto comes amid spikes in anti-homelessness policing in cities across California, or that cops denounced S.B. 57 on grounds remarkably similar to Newsom’s. ’Twas always thus: Democrats spearheaded the 1990s crime bill that added accelerant to the “war on drugs”; they’ve more recently been having a partywide competition to see who might condemn the “Defund the Police” slogan in the most histrionic fashion.

Such Democrats help defeat critical public safety measures such as safe injection sites; good leaders would actually use their power to break the grotesque pattern drug policy is stuck in, blowback be damned. But from the supine position they insist they’ve been forced into, the political calculus seems easier: Social disorder is widely unpopular, and it’s been simple enough to convince people that it can only be solved through some combination of cops and courts. Combine this default position with a media prone to panic-stoking, and you’ve got a situation in which acting tough on the powerless is as no-brainer a campaign move as a flag pin on your lapel.

It’s apparently not enough for politicians simply to play the hits again and again and again; they have the gall to act like doing so makes them nuanced philosopher kings—as if Gavin Newsom did this out of wisdom rather than calculated indifference. But all Newsom has done is respond to the constant demand of liberal thought-leaders to generate a “Sister Souljah moment,” in which one demonizes an erstwhile member of your political tribe to burnish one’s toughness and independence. But there’s no cheaper version of this tactic than denigrating impoverished drug users whose lives Newsom could just as easily save with the stroke of his pen. The best solution to the overdose crisis may generate a few bad-faith attack ads. Get over it!

What we need is a new framework for addressing social strife, and for leaders to have the spine to stand behind it. Harm reduction offers exactly that—and advocates did years of work building support and capacity to open overdose-prevention centers that save lives. A worthy leader would have joined them. Newsom isn’t one.