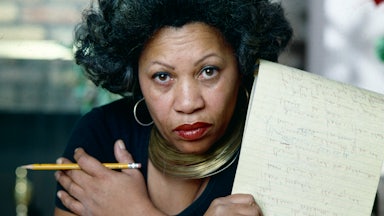

For 121 years, the Nobel Prize for literature has sought to honor the best writing in the world, and for 121 years everyone has argued that it has managed to do no such thing. In the battle between the Swedish Academy and its most fearsome opponents, annoying people on Twitter (as well as Twitter antecedents, such as the newspaper column, the radio dispatch, and probably something involving a telegraph and/or a horse), neither party has scored a decisive victory. For every Sholokhov, there is a Canetti. For every Sully Prudhomme, a Toni Morrison. For every Winston Churchill, a … Rudyard Kipling? OK, wait, never mind.

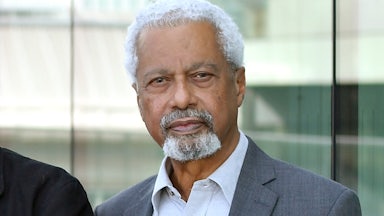

Beset by controversy, ever-changing taste, and the rise of competing mediums like “prestige television” and “trampoline accident TikToks,” the Nobel Prize has, in recent years, faced an identity crisis. The result has been a series of winners who raise questions about the nature of the prize itself: Does oral history constitute literature? Do Bob Dylan’s songs about being horny for Alicia Keys constitute literature? Does Abdulrazak Gurnah even exist, or is he, like JMG Le Clézio before him, an elaborate troll by the Academy designed to determine how many people would pretend to have read an author they had obviously never heard of? And there is the most important question of all: Is New Haven, Connecticut, the center of the literary universe?

This column’s record of predictions is mixed. On one hand, in 2016 I wrote that Dylan would not win the Nobel, which he went on to win a few days later. (The Swedish Academy has yet to return comment as to whether the Traveling Wilburys should be considered honorees by extension or, indeed, if it was specifically acknowledging Dylan’s monumental work on “Dirty World.”) On the other hand, in 2021 I wrote that Haruki Murakami would not win the Nobel, and as of this writing he hasn’t. In baseball, a .500 batting average is phenomenal. And the Nobel is a lot like baseball: It’s increasingly irrelevant and overhyped, and it could probably use more—rather than less—corruption to make things more interesting.

Who will win in 2022? Not Haruki Murakami. Not Javier Marías, who died in September, therefore making his novels about how being really into having sex with hot women is actually a form of philosophical inquiry—as long as you also have a nebulous job as a spy—ineligible. Sadly, it won’t be Hilary Mantel, who passed away shortly after Marías, therefore robbing us of the opportunity to observe the notoriously even-keeled English media try to square her acerbic anti-monarchism with its own deranged deification of Queen Elizabeth II. It would have been soul-stirring to see The Sun’s headline: “DEPRAVED QUEEN HATER WINS FOREIGN AWARD.”

But who will lose the Nobel? Probably cancel culture. Reporting—which is to say, stray conversations with drunk Europeans—indicates that compared to the other issues of international importance (the war in Ukraine, the rapid acceleration of climate change–related natural disasters, energy shortages in Germany, the continued existence of Imagine Dragons, Paramount’s burial of the new Fletch movie, which features Jon Hamm’s first great comic performance), intellectual life on the Continent has been focused on the backlash to what France—a country that literally invented overreacting to things—has declared “le Wokisme.” (Earlier this year, even Vladimir Putin took issue with cancel culture, not not blaming it for his decision to invade Ukraine.)

The Nobel is not immune to these conversations. Recently, following the horrific attack on Salman Rushdie, David Remnick and Bernard-Henri Lévy both published columns arguing that the novelist deserves the Nobel in recognition of his work on behalf of free expression—and also because he was brutally stabbed (and also—implicitly—because he had to endure the indignity of convalescing in Western New York).

These two pieces—one by a respected magazine editor, one by an inane ex-philosopher with a Crash-style erotic attraction to war-zone self-portraiture—only gesture at Rushdie’s literary accomplishments, which were undeniable for most of his career until they devolved into Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me–style satire and what the critic Leo Robson described as “little more than an exercise in googling, an attempt to sell the listicle as literature.” For what it’s worth, the official position of The New Republic’s yearly Nobel column is that Rushdie is a deserving Nobel laureate, both for his early revolutionary polyphonic novels and for his later work in other media—namely Facebook Messenger, where he composed a number of horny texts of true literary significance. (Though Adam Levine’s work in this tradition has received more recent attention, Rushdie’s influence will resonate through the generations.)

What Remnick and shirt-button annihilator Lévy seem to want from the Academy is an explicit political statement. Alas, this is not how the prize works: The Nobel never makes an explicit political point, not when it can obscure it in vagaries and plausible deniability. Was Harold Pinter awarded the prize in 2005 for his brave opposition to the Iraq War or for his plays depicting English people as cold and terrified of sex? Was Dario Fo awarded in 1997 for his political satire or because the Academy mixed him up with a different, better writer? More importantly, the Nobel Prize already made the boldest statement it could on behalf of free expression when it stood up to the woke left, who insisted that Peter Handke was undeserving simply because he had spent several decades doing genocide denial.

Whatever the merits of Remnick’s and Lévy’s pieces, they were likely redundant. Whether the Swedish Academy awards the prize to Rushdie or not, it is inevitable that it is thinking along similar lines, only more stupidly. “Could we give the prize to Jeanine Cummins?” a member of the Academy probably asked at some point during the deliberations. “Could we give it to the Harper’s Letter?” “Could we award it to J.K. Rowling but specify that it’s for her tweets and not her books?” “Are Bill Maher’s New Rules literature?”

Like cancel culture itself—and also like fish if you’re not very good at fishing—discussions of cancel culture are slippery, elusive, and hard to pin down. Anyone who wins the award this year can, and likely will, be claimed and celebrated on behalf of free speech and bravery in the face of the censorious mob, and against the excesses of political correctness. No matter who receives the prize money, cancel culture has already lost.

Of course, there are even further-flung political obsessions in which Nobel watchers can spend several hundred hours entangled. Could the Swedish Academy award a Ukrainian writer as an act of solidarity in opposition to Russia’s flailing invasion? Could it give to all those people who tweet long threads about Russian tank failures or to Volodymyr Zelenskiy, for his shirts? Perhaps the committee could make a principled statement about reproductive rights by honoring Annie Ernaux, whose Happening is one of the most profound and moving accounts of the horrors that attend the illegalization of abortion? (Ernaux is also notable for her contribution to France’s most important literary export: books about having an obsessive affair with someone who barely talks to you.) Or could the Academy fight inflation and climate change simultaneously, awarding William Volmann in a desperate attempt to stop him from publishing six 800-page books a year?

Only one thing is certain: Whatever I write in this column will be proven wrong, likely in catastrophic fashion, when the Nobel Prize in literature is announced on October 6. I know that earlier in this column I said that my record was mixed, but I was being charitable. Seven years into my career as America’s chief Nobel Prize in literature speculator, it has become clear that I simply am not good at this. (For the record: I have listed Olga Tokarczuk and Svetlana Alexievich as favorites, explicitly said that Dylan, Louise Glück, and Handke wouldn’t win, and failed to even mention Ishiguro and Gurnah.)

I cannot stress this enough: Do not listen to me; I am very bad at this. And for the love of God, do not make any bets based on this column. (Though if you do decide to gamble please go to The New Republic’s new proprietary sportsbook, HOUELLEBETS: For every $100 you spend, you get 10 remaindered copies of Michel Houellebecq’s correspondence with Bernard-Henri Lévy.)

Ladbrokes Favorites That Actually Have a Shot

- Pierre Michon (French quasi-biographer; 12-1 odds)

- Annie Ernaux (French autofiction pioneer; 20-1 odds)

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Kenyan novelist and perennial Nobel favorite; 16-1 odds)

- Gerald Murnane (Australian small-town resident; 20-1 odds)

- Can Xue (Chinese novelist and short story writer; 40-1 odds)

For the first time that I can remember, there is substantial division between Ladbrokes and the (mostly random) Scandinavian people I talk to every year about the Nobel. The speculation among those in the know (a select group of Swedes who I pester every fall) is that the prize will either go to a Scandinavian or an Asian writer. The thinking—if one can call it that—goes something like this: Having corrected its most glaring mistake (the failure to award a Black African writer for more than 30 years), the Academy will either continue to fix its errors (in this case, the lack of Asian laureates) or look closer to home. Bettors, on the other hand, seem to believe that the Academy will do what it always does and award a self-serious European who is barely read outside the Eurozone.

I’ll be honest: I have no idea why Michon became the favorite; that there’s this much smoke around him probably means something. But then again there’s always smoke—last year, I thought that a spate of press around Jon Fosse portended big things, and in 2016 I notoriously interpreted signs that an American would win in 2016 as proof that it was, at long last, Don DeLillo’s year. But who knows, perhaps the Academy was freshly moved by Michon’s literary treatment of two contemporary icons: Van Gogh and Rimbaud.

Ernaux is becoming a Ngũgĩ-like presence on this list, a perennial front-runner who never quite crosses the line. As a memoirist, she could be seen as a departure for the Academy, but in the age of autofiction, anything goes. Anyway, if Churchill could win for his autobiographical work If I Did It (and by “It” I Mean the Bengal Famine), Ernaux can surely win for her searing excavations of her own past.

Speaking of Ngũgĩ, he remains perhaps the most deserving candidate on the list; the Academy surely knows that it’s running out of time to give him, at 84, the prize—something that is only made more glaring by the recent, untimely deaths of Marías and Mantel. But it would be surprising if it gave him the award a year after giving it to Gurnah—who was arguably better known for his critical work on Ngũgĩ and Rushdie than for his novels before last year. (This is, I think, what passes for a joke in Stockholm.)

Can you imagine the excitement at the men’s shed—you read that right—that Murnane hangs out at if he won the Nobel? Whether he’d end up buying the bar a round of Foster’s or everyone would end up buying a round for him, it would be an exciting three minutes—until everyone went back to watching the rugby. As for Can Xue? Imagine the citation: “For her uncategorizable and strange works that read like a Benadryl fever dream.” I don’t see it happening.

There’s a Lot of Buzz Around These Norwegians—Well, Not Dag Solstad (Sorry, Dag Solstad)

- Jon Fosse (Norwegian septologist; 20-1 odds)

- Karl Ove Knausgård (Rugged Norwegian season expert; 33-1 odds)

- Dag Solstad (Norwegian trickster; no odds)

The Swedish Academy, like most groups mostly composed of white, male tenured professors nearing or past retirement age, is lazy. And like those groups it also has an unfortunate predilection to honor people like themselves—in this case dour northern Europeans.

The thinking behind this grouping is more of a hunch. The last Scandinavian laureate was Tomas Tranströmer, the leading Swedish poet of his generation and author of, among other things, the seemingly A.I.-titled collection of poetry, The Sorrow Gondola. (Italy, which has not produced a laureate since Fo won for his contributions to the clowning arts in 1997, should sue.) The timing is right for a Scandinavian, but only one country in the Great White North is producing literature (and top-class strikers, for that matter): Norway.

There is an inordinate—and somewhat shocking—amount of speculation surrounding Knausgård, who is rumored to be a favorite of at least one member of the Nobel Committee. This would be hilarious. It would cause a multiday meltdown on the internet and make Twitter more or less unusable—which is reason enough to support the choice. At 53, Knausgård is young—by recent Nobel standards, at least—but his monumental My Struggle (No, Not That One, a Different One) is surely what he would be honored for at any age. The only question is if the Academy would be too concerned that Knausgård would use the prize money to self-fund an 80,000-word dispatch about following Wilco around on its European tour—and, through extensive interviews with Jeff Tweedy and his son, interrogating his own history of bad parenting.

I would personally give the edge to Fosse, 10 years Knausgård’s senior (and his former writing teacher), for his recursive, dreamlike works about people looking at fjords and thinking about all the ways that they—and their families and ancestors and friends and also sometimes people they pass on the street—have fucked up in their lives, specifically in and around fjords. But Fosse has also broken from precedent, daring to write a septology that has little to do with the tradition of authors like C.S. Lewis and J.K. Rowling (whose septologies are about mysterious wizards and Jesus and/or mysterious wizards who might be Jesus) and is instead concerned with the ultimate mysterious wizard: the meaning of life.

No one is talking about Dag Solstad, which is sad. Poor Dag Solstad.

What if the Nobel Prize Only Goes to Europeans From Now On?

- László Krasznahorkai (Hungarian patron saint of fans of this column who are over 30, which is to say unemployed grad students; 16-1 odds)

- Mircea Cărtărescu (Romanian patron saint of fans of this column who are under 30, which is to say soon-to-be-unemployed grad students; 20-1)

- Edna O’Brien (Breakout star of the Ken Burns documentary Hemingway; 20-1 odds)

- Dubravka Ugrešić (Croatian writer; 25-1 odds)

- Emmanuel Carrère (French Geoff Dyer? But less funny? 25-1)

- Hélène Cixous (French literary theorist; 25-1 odds)

- Maryse Condé (French-Guadeloupean novelist; 25-1)

- Ryszard Krynicki (Polish poet; 25-1 odds)

- Péter Nádas (Hungarian atavism—in a good way; 28-1)

- Ismail Kadare (More important Albanian cultural export than Bebe Rexha, less important Albanian cultural export than Dua Lipa; 33-1 odds)

- Botho Strauss (German playwright who is just a little bit more German than you would like him to be; 33-1 odds)

- Ivan Klíma (Czech GOAT; 33-1 odds)

- Sebastian Barry (Yet another Irish novelist and playwright; 33-1 odds)

- Milan Kundera (Teen idol—for dorks; 50-1 odds)

- Jean-Luc Godard (Dead French genius; no odds)

Europe famously achieved the peak of its cultural influence in 1974, when four majestic Swedes—Agnetha, Björn, Benny, and Anni-Frid—walked onto the Eurovision stage and introduced the world to “Waterloo.” Since then it’s been a slow and then increasingly rapid decline (with the occasional good blip, like ABBA’s 1976 album Arrival, perhaps the high water mark of Western art).

It’s no wonder, then, that most of the European pool is a gloomy bunch. Kadare, Ugrešić, and Nádas have been climbing in recent years, a clear sign that the Academy has been infiltrated by editorial assistants. Cixous, meanwhile, would be the second literary critic—OK, she is regularly referred to as a “theorist,” but that’s just French for “critic,” which is English for “a brainiac who keeps yucking my yum”—to win in a row. The Academy made a grave mistake by giving last year’s award to Gurnah, who was a largely unknown literary critic, thereby giving hope to the tens of thousands of guys on Twitter who post numbered threads about cadence in the work of Jens Peter Jacobsen. There should be a price for doing this. (The price, to be clear, is trial at The Hague.) If Cixous wins, the Nobel will have gone to a poet and two literary critics in three years—all of whom are professors. This is unacceptable.

Krasznahorkai, meanwhile, has made his entry into top-flight Nobel Prize speculation, suggesting the readers of this column have begun betting on it in earnest. (If you’re reading this, please don’t—Krasznahorkai won’t win, and it’s better for you to spend the allowance you get from your parents on staples like pasta and soup. Also, maybe buy a Swiffer mop and clean up your basement? The part of the floor between the computer and your stack of Shklovsky paperbacks is disgusting.) The ultimate effect of a Cărtărescu victory would be a massive, collective orgasm whose sensation would be limited to men who, in the past 10 years, asked their local tattoo artist to cover their Pynchon muted horns with an image of Krasznahorkai’s Baron Wenckheim. It goes without saying that this would also be the first non-self-inflicted orgasm any of those men had had during that period. Godard is technically ineligible, due to being dead, but as one of the two or three greatest Europeans of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, he should win anyway.

These Favorites Definitely Aren’t Going to Win

- Michel Houellebecq (The Gollum-like physical manifestation of Europe’s rightward drift; 16-1 odds)

- Haruki Murakami (A pair of pristine orange Nike Air Zoom AlphaFly Next% sneakers; 16-1 odds)

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (First, but definitely not the last, Nobel contender to be best known for a TED talk; 20-1 odds)

- Sally Rooney (Irish novelist whose books people pretend take place in Brooklyn; no odds)

- Elena Ferrante (Italian Banksy, also the actual Banksy; no odds)

- Claudio Magris (Italian translator; 25-1 odds)

After Philip Roth’s death in 2018, we were robbed of one of the funniest recurring images in American letters: Roth (reportedly) going to his agent’s office on the day of the announcement to await a call that never comes. I have no idea if Murakami wants the Nobel Prize or if he expects it—and he shouldn’t, because he is not going to win—but I have decided to now picture Murakami doing exactly this. He laces up his running shoes. He puts on a Stan Getz record on the most expensive, minimalist stereo system you have ever seen. Pasta boils on the stove in a gleaming, spotless pot. Murakami sits by the phone in an Eames chair, and he loads YouTube and watches the announcement muted, with subtitles: some Swedish words—Jon Fosse—some more Swedish words. He steps outside and runs 22 miles without stopping.

Houellebecq won’t win, not because the Swedish Academy is too afraid of the lecture he would give (though it should be) but because it’s afraid of the cleaning bill that would follow—and also because a year ago it gave the Nobel to Gurnah for his moving portraits of migrants, and giving it to someone who thinks those people should stay where they came from is insane, even by its standards. J.K. Rowling won’t win, not because of her tweets or for her autofiction (crime novels about getting revenge on people who have tweeted mean things about you) or because she may be the single worst sentence writer of the last century, but because the Academy found her decision to write a three-hour movie about “Wizard Hitler” distasteful. Elena Ferrante won’t win, not because the Academy thinks she doesn’t deserve the Nobel Prize, but because it wants her to reveal her identity the right way (as a cannoli singing “That’s Amore” on The Masked Singer).

The British Economy Is Collapsing, and So Are Its Nobel Prize Odds

- Salman Rushdie (I’m not going to get canceled for this, it’s not worth it; 16-1 odds)

- Robert Macfarlane (A little too into mountains; 33-1 odds)

- Ali Smith (Soulful Scottish season expert; 33-1 odds)

- Martin Amis (Christopher Hitchens biographer; 50-1 odds)

- Ian McEwan (Somehow simultaneously Tony Blair and Keir Starmer, as well as a writer who would absolutely write a speculative fiction novel about a person who was simultaneously Tony Blair and Keir Starmer; no odds)

- J.K. Rowling (Future plaintiff in a lawsuit against Alex Shephard and The New Republic; no odds)

- Tom Stoppard (Author of the line “From my point of view the Jedi are evil!”; no odds)

- Julian Barnes (Honestly, just seems like a nice bloke, and the books are always solid; no odds)

During her long reign, Queen Elizabeth oversaw an increasingly marginal and bedraggled United Kingdom that has, with a few exceptions (John Akomfrah, Beth Orton, Steven Gerrard, Stormzy), produced little of cultural importance. Or maybe it did and the ascent of Downton Abbey and The Crown—two of the most vile and inane TV shows ever produced—has retroactively obscured every recent or semirecent British cultural achievement. Still, Elizabeth had a good run, overseeing more British Nobel victories than any other monarch, past or surely future, unless “King Charles III” lives to age 143. Kazuo Ishiguro won the prize in 2017, so between that and the Swedish Academy’s mourning period for Elizabeth II, commonly referred to in Sweden as “The Queen of Literature” (note to fact-checker: Please verify), it is unlikely that the Nobel will be, um, coming home. (One other thing that won’t be coming home: the World Cup in December—not until English fans stop singing “Sweet Caroline,” an offensive appropriation of Irish-American culture.)

Rushdie won’t win because even the Swedish Academy isn’t dumb enough to give Bernard-Henri Lévy a pretext for feeling even more smug and self-involved than he already is. Martin Amis won’t win because he has given up on being a novelist, but not in a cool, renunciatory way like Karl Ove Knausgård (who is writing novels and may win). Ian McEwan won’t win because even the Swedish Academy isn’t dumb enough to award a writer who wrote a book with the most embarrassingly British plot of all time (guy prematurely ejaculates, and it ruins his life). If Robert Macfarlane won, it would be the first Nobel for a Radiohead collaborator (unless Herta Müller had a jam session with Colin Greenwood that hasn’t been documented), but he won’t win. Julian Barnes should win, because he’s a fine novelist and critic, but he won’t, because it feels like everyone has forgotten about Julian Barnes, even his boys (many of whom are on this list) :(.

These Americans Most Definitely Aren’t Going to Win

- Stephen King (In one book, a spooky car kills people; in a different book, a spooky clown kills people; in another book, a spooky duvet kills people; he has written 600 of these; 16-1 odds)

- Cormac McCarthy (Mud-spackled Stetson ; 20-1 odds)

- Garielle Lutz (American experimental writer; 20-1 odds)

- Thomas Pynchon (American novelist and stoner icon; 20-1 odds)

- Don DeLillo (author of White Noise—the novel, not the bloated E.T. homage); 20-1 odds)

- Colson Whitehead (American novelist; 33-1 odds)

- Edmund White (American legend; 33-1 odds)

- Jamaica Kincaid (American novelist and gardening icon; 20-1 odds)

- Robert Coover (Somehow still alive American writer; 33-1 odds)

- Wendell Berry (Somehow still alive American writer and gardening icon; 33-1 odds)

- William Vollman (Writes books by spinning a giant wheel with entries on it like “train conductor,” “nuclear power,” “perversion”; 33-1 odds)

- Joyce Carol Oates (Wan little husk; 33-1 odds)

- Martha Nussbaum (American philosopher; 33-1 odds)

- Charles Simic (American poet; 40-1 odds)

- Jonathan Franzen (Podcast subject; no odds)

- Marilynne Robinson (Writes books about Calvinism for Episcopalians who go to church twice a year; 50-1 odds)

Two Americans have won in the past decade—Louise Glück, reasonably, and Bob Dylan, insanely. That’s a lot of Ws for a country whose writers were accused, in 2008, of being “too sensitive to trends in their own mass culture.” The Swedish literary historian and Academy permanent secretary Horace Engdahl’s remarks were controversial and widely derided, though he was probably right about the mass culture thing. In any case, an American isn’t going to win! And if an American were to win, it wouldn’t be fucking Stephen King, who like J.K. Rowling is probably better known for his tweets than for his novels but who unlike J.K. Rowling had his books adapted by Stanley Kubrick and Brian DePalma, instead of Chris Columbus and Mike Newell. Why are you idiots betting on Stephen King?

Garielle Lutz makes her (surprising) entrance into top-flight Nobel Prize speculation, as do Edmund White and Colson Whitehead. This is, strangely, the strongest showing American writers have had in years. Does this suggest anything about the Swedish Academy’s intentions? No. It simply indicates that the bettors are even more deluded than usual. Jonathan Franzen is currently on a victory tour of Europe, celebrating the publication of Crossroads in France (where Russ’s affair with a woman only 10 years younger than himself has been greeted with mockery and confusion), but the Academy saw the Berglund family in Freedom as a grave insult to Sweden and permanently excluded him from consideration.

Reportedly, the members of the Swedish Academy are huge fans of Andrew Dominik’s Blonde, organizing Clockwork Orange–style forced screenings for new recruits. “Of course, it took an Australian to finally make a great American movie,” one member said, cruelly ignoring Peter Weir’s Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. Chatter in Stockholm suggests that the literature prize may be rebranded as a film prize simply to make Dominik eligible. (The Academy also loved the George W. Bush stuff in Killing Them Softly.) How this plays out for Joyce Carol Oates is unclear. The Academy is closely monitoring the “literary non-hottie” debate to determine the relationship between the film and its source material. Also, last year in this column I defended her tweets, and since then she has posted some of her most insane and offensive shit yet. It’s hard to defend such material on the merits, but still: Keep tweeting, queen.

Cormac McCarthy inexplicably did something that this column said he would never do—finish his long-awaited novel The Passenger—boosting his reputation at just the right time. Unfortunately, he won’t win because of the ammoniac mist rising up from the marsh in the inexplicable darkness, the jagged, sepulchral mountains stabbing the horizon, and also because the lead characters of his new books are named Bobby and Alicia Western—simply too on the nose. As for Pynchon and DeLillo, they’re 85 years old. That’s almost as old as George Burns was when Eminem penned his classic dis, “Look at the store clerk, she’s older than George Burns.” Burns, however, was already dead, and Pynchon and DeLillo are—blessedly—alive. So give them the Nobel!

These Canadians Are Also Not Going to Win

- Anne Carson (A single plum, floating in perfume, served in a man’s hat; 20-1 odds)

- Margaret Atwood (Cursed to continue writing new material for The Handmaid’s Tale television show, which is somehow on season 17; 20-1 odds)

I don’t know how I know this, but it’s true: Anne Carson is too weird for the Swedish Academy, and Margaret Atwood is too normal. Also, Alice Munro winning in 2013 means another Canadian will not win again until sometime in the twenty-third century, when Sweden and Canada are the world’s only two habitable countries and the prize is a single extra water ration.

Could One of these Writers win?

- Mia Couto (Mozambican novelist; 25-1 odds)

- Scholastique Mukasonga (French-Rwandan novelist; 25-1 odds)

- Nuruddin Farah (Somali novelist; 25-1 odds)

- Amitav Ghosh (Indian historical novelist; 33-1 odds)

- Andrey Kurkov (Ukrainian crime novelist; 33-1 odds)

- António Lobo Antunes (Portugese novelist; 33-1 odds)

- David Grossman (Israeli novelist; 33-1 odds)

- Homero Aridijis (Mexican poet; 33-1 odds)

- Mahmoud Dowlatabadi (Iranian novelist; 33-1 odds)

- Marie NDiaye (French novelist; 33-1 odds)

- Yan Lianke (Chinese novelist; 33-1 odds)

- Ivan Vlaidslavic (South African novelist; 40-1 odds)

- Linton Kwesi Johnson (Jamaican dub poet; 40-1 odds)

- Murray Bail (Australian novelist; 40-1 odds)

- Xi Xi (Hong Kong–based Chinese writer and poet; 40-1 odds)

- Ko Un (Canceled South Korean poet; 50-1 odds)

- Yu Hua (Chinese novelist; 50-1 odds)

- Zoë Wicomb (South African novelist; 50-1 odds)

- Georgie Gospodinov (Bulgarian poet and novelist; no odds)

As is extremely obvious, this column does not take the Nobel Prize in literature very seriously. There are many reasons for this. The first is that literary prizes are inherently pretty ridiculous. The second is that the Nobel Prize is the most ridiculous of all—not only because the most esteemed and famous literary prize in the world is given out by a bunch of scandal-prone Swedish academics but mostly because of that. The third is that reflexive irony and glibness are useful in obscuring an underlying seriousness about literature and literary culture that I would rather not reveal. Oh wait, shit, here’s another joke about Michel Houellebecq’s physical appearance: Um … he looks like a wax figure of Steve Buscemi that got left out in the sun! No, hmm … he looks like a Notre Dame gargoyle that got charred during the fire! Or, er … he’s a hideous bird!

Anyway, while the speculation in and around Stockholm suggests that the Academy is poised to pick a well-known writer—though perhaps not a superstar on par with Dylan or Ishiguro—the best use of the Nobel Prize in literature is, in my opinion, highlighting neglected but worthy writers from around the globe. The Nobel has often failed in this task, largely awarding Parisian writers or, occasionally, German ones (who live in Paris).

The above compilation of writers on the Ladbrokes list is striking for its range and the generally high literary quality. Some of these writers have appeared on the list for years and will continue to do so because bettors aren’t the world’s most imaginative people. Others are newcomers, like Andrey Kurkov and Amitav Ghosh. Most of them are simply great writers, and while their victory wouldn’t be as satisfying as Pynchon’s (because that would feel triumphant) or J.K. Rowling’s (because this column strongly endorses shitshows and absurdities), it would be a good thing for literary culture, which has been having a rough time of it ever since the invention of the quote-tweet feature.

But who knows! Maybe the Swedish Academy really will give it to Murakami, at which point I will fly to Japan, steal all his T-shirts, and slowly eat them in a fugue state of disgust and grief. Please don’t give it to Murakami.