With near daily mass shootings and constant media attention to crime in America, it has become increasingly difficult to deny that the United States is considerably less safe than other wealthy nations. During the lead-up to the midterm elections, lawmakers from both sides of the aisle turned to what has long been regarded as the common sense response: calls to increase funding for police and prisons. And for the first time in recent memory, this electoral strategy failed.

Despite being subjected to intense political and mass media rhetoric about a supposed “crime wave” for months on end, only 11 percent of people in exit polling stated that crime was their primary concern. Meanwhile, criminal legal reformers such as Pennsylvania’s John Fetterman, who stood by his advocacy for clemency in cases of people who had been convicted of violent crimes rather than shying away from it as if a vulnerability, won despite the fearmongering strategies of their opponents. Similar results were seen in places as varied as California, Minnesota, and Texas. This signals potential for a major shift in American politics, and an opportunity to change how we as a nation conceive of crime, violence prevention, and public safety.

Millions of Americans, including many living in criminalized Black and brown communities, have been inculcated, via decades of crime journalism, copaganda, and “tough on crime” campaign rhetoric, to reflexively support such policies in the belief it will protect them. But after a half-century of this policy playing on repeat—and endless studies of its effects from researchers—there is no good evidence that more police or incarceration reduce crime or violence. Instead, there is abundant data showing police-centric public safety policy undermines public health, harms families, makes millions of Americans sick, and leads to a plethora of long-term social and economic harms.

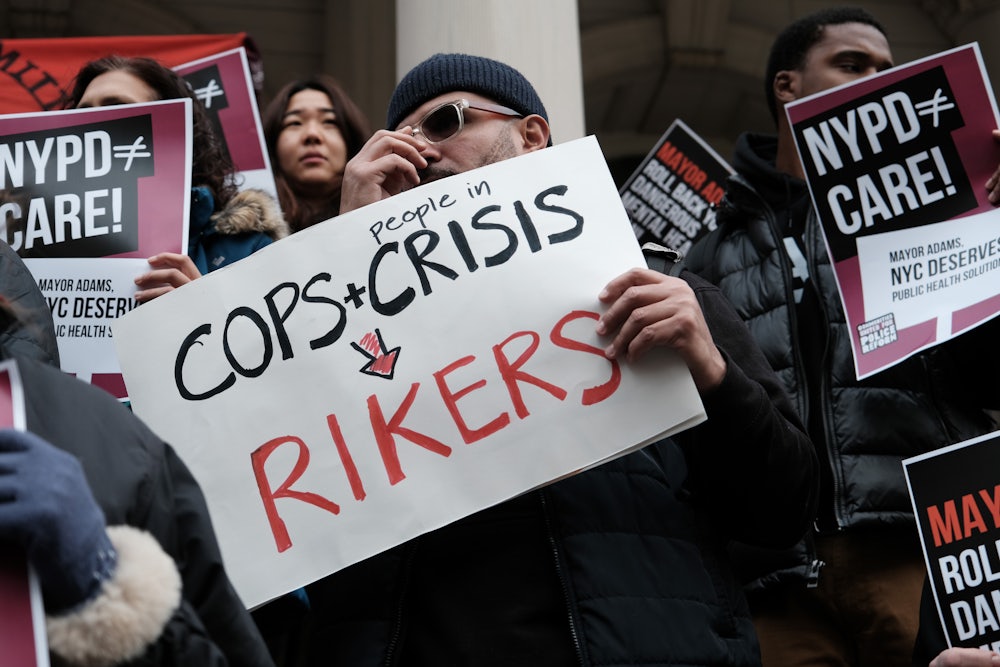

But this reliance on police as the centerpiece of public safety has nonetheless remained our default policy because most Americans, including many well-meaning lawmakers, don’t know where else to turn in order to address fears of violence—as well as the real thing—in our communities. This is largely attributable to the fact that “public safety” has historically been reduced—in part by the influence of the police-adjacent field of criminology—to a narrow matter of crime rates and police tactics. In the process, the concept of public safety has been cordoned off from the policies that best serve it: public systems for supportive care like health care, addiction treatment, supportive housing, and guaranteed basic income programs. These, it’s assumed, are a matter of public health policy, not safety.

If we want to make America safer, we need to break down this false division and embrace what data make clear: Health policy is safety policy. A large body of research shows that the lack of safety in our communities is inseparable from the fact that the U.S. remains the world’s only industrialized nation to refuse to provide universal health care as a basic public service to its citizens. As a result of this policy choice, there are now over 31 million U.S. residents without health insurance. With the end of the federal government’s Covid-related emergency provisions, up to 15 million more people are set to join them.

Where do these people excluded from care in America’s for-profit medical landscape end up? Millions of them fall into crisis and, as a result, commit crimes, leading to arrest and incarceration in jails and prisons—costly public institutions that inflict health-harming punishment rather than providing the services people need. A recent report illustrates this dynamic, showing that 50 percent of individuals in state prisons as of 2016 (the most recent available data) were without health insurance at the time of their arrest. By comparison, only 9 percent of the overall U.S. population was uninsured in that same time period. Lack of access to health care, such findings suggest, increases the risk of crime, violence, arrest, and incarceration.

For many people, arrest and incarceration perversely leads to temporarily improved health care relative to what they had received on the outside. For example, over a quarter of people in state and federal prisons who entered prison with a chronic condition were first diagnosed with this condition while incarcerated. Realities like this have led some to suggest that prisons are good for health—an idea that has also been part of the false claim that they deter future crime.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Health care quality inside jails and prisons is notoriously deficient and inadequately regulated. Unconstitutional medical neglect runs rampant, with nearly 20 percent of people in prisons reporting that they have not had a single medical appointment since they were first incarcerated. While 43 percent of people in state prisons have been diagnosed with a mental health condition, 74 percent report not having received any mental health care while incarcerated.

This lack of care has long-term consequences, with each year of incarceration associated with a two-year reduction in life expectancy. And these harmful health effects of incarceration don’t only harm those who have been incarcerated; they also spread to their families, communities, and entire counties. This does nothing to deter crime nor to “rehabilitate” incarcerated people, but it does partially explain why incarceration actually increases subsequent criminal behavior.

The real conclusion to be drawn from the relatively better availability of health care inside jails and prisons for some people is this: Our for-profit health care system is failing abysmally to provide basic care for those with the greatest need. This, in turn, fuels interrelated cycles of poverty, trauma, addiction, crime, and violence.

These health policy failures are a major driver of America’s failed public safety paradigm. But, despite intense political and media attention paid to crime and public safety policy over the last two years, almost no media or political attention has been paid to a constant stream of research repeatedly demonstrating that expanding supportive services, especially health care access, is an extremely effective policy for reducing crime and improving shared safety.

In studies released this year alone, one found that men who lose access to Medicaid eligibility are 14 percent more likely to be incarcerated over the following two years relative to a matched comparison group. That goes up to 21 percent for people with histories of mental health diagnoses. A second showed that increased access to health care through Medicaid expansion for formerly incarcerated people substantially reduces rates of rearrest for violent crimes and public order crimes, with 16 percent reductions in violent crime observed over the two years after release. A third found police arrests significantly declined after the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid access, leading to a 25 to 41 percent drop in drug arrests and a 19 to 29 percent decrease in violence-related arrests.

In 2020, two studies demonstrated that Medicaid expansion is associated with reductions in burglary, vehicle theft, homicide, robbery, and assault, resulting in significant financial returns that offset the public cost of ensuring a right to health care. Another showed that the 1990 Medicaid expansion, which provided increased health care access for Black children, led to a 5 percent reduction in their rate of incarceration by age 28, mostly due to reductions in financially motivated crimes. And a 2021 study showed expanding outpatient mental health care offices substantially reduces crime and crime-associated costs to communities.

These recent findings join others that have repeatedly demonstrated that not just health care but a wide range of supportive public services—from emergency financial assistance, addiction treatment, and guaranteed basic income, to summer jobs programs and neighborhood beautification—are very effective at reducing crime and protecting community safety. By contrast, data have repeatedly shown that U.S. policing and punishment models, despite their already world-leading budgets, do not make Americans safer.

To finally build safety, health, and trust in American communities, we need our lawmakers to confront the fact that punishment cannot serve as a substitute for freedom-enabling care. Voters, including those in Republican-run states, are showing they are ready to support those who do.