FREE-FOR-ALL HELLSCAPE.

This term was written in black marker on a small whiteboard, held—as whiteboards in House Oversight Committee hearings often are—by Representative Katie Porter. The words FREE-FOR-ALL were scrawled in lower case; HELLSCAPE was rendered in dramatic capitalization, accentuating its apocalyptic connotations.

The early February hearing on Twitter’s response to the Hunter Biden laptop story was a priority for the new Republican majority. But Porter, typically known for her pointed grilling of hapless witnesses, kept her comments concise, asking no questions. Instead, she ended her remarks by quoting Twitter owner Elon Musk, who said in October that the site “cannot become a free-for-all hellscape.”

“The Oversight Committee, like Twitter, or any other social media company for that matter, cannot become a ‘free-for-all hellscape’ where anything goes,” Porter concluded with a flourish, pulling out the whiteboard to punctuate her words, as if the term “free-for-all hellscape” could not truly be understood without a helpful visual aid and portentous capitalization.

Porter’s contribution befitted a hearing that she and her fellow Democrats viewed as a ridiculous waste of time. But the scribbled words were less important than the whiteboard itself, a prop that has become inextricably linked to the California congresswoman’s identity. In the Monopoly board of political success, Porter’s avatar would be a whiteboard, passing “Go” for every government bureaucrat or corporate official she questions, collecting social media clout and liberal adoration along the way. That February afternoon, the whiteboard fulfilled its purpose: A tweet from Porter’s official account with a clip of her remarks went mildly viral, receiving thousands of likes and hundreds of thousands of views.

I spoke to Porter in her Orange County campaign office the week after the free-for-all hellscape of a hearing. She told me that she employed the whiteboard judiciously, depending on the subject of the hearing “and what kind of message I want to get across in that moment to the witness.” She acknowledged that it had become somewhat of a calling card: “There are definitely people like, ‘Sign my whiteboard.’ I mean, there are definitely people who, they’re captivated by it. They’re like, ‘You’re the whiteboard lady!’” Porter told me. “I think that’s a sign you’re connecting with people. So I try to be thoughtful about when to use it.”

Maryland Representative Jamie Raskin, the ranking member of the House Oversight Committee, told me that, as a former law professor, Porter—who specialized in bankruptcy law—is “uniquely suited to teaching bureaucrats in the country a lesson about how power works.” He continued: “That’s the effectiveness of her whiteboard. Has whiteboard, will travel.”

Porter’s prominence is unusual for a representative who just began her third term, but her sharp, precisely worded questions, authoritative mien, and savvy prop usage in hearings—not typically thrilling arenas for political jousting—have continued to propel her notoriety. She has a shrewd eye for powerful symbolism; the congresswoman garnered attention in January for wearing a bright orange dress while reading the book The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck during the many speakership votes of Kevin McCarthy—a tome that happens to have a bright orange cover, the same shade as her outfit. (Porter later insisted that the choice of book had been purely coincidental.)

As she embarks on a high-profile and likely high-cost run for the California Senate seat soon to be vacated by retiring Senator Dianne Feinstein, Porter’s whiteboard is a distinguishing feature, an embodiment of her belief that the powerful should be accountable to the powerless in one clear symbol. Porter was the first Democrat to launch her Senate campaign in January, anticipating (and perhaps precipitating) Feinstein’s retirement announcement. She was quickly followed into the race by fellow Representatives Adam Schiff and Barbara Lee, two established and respected lawmakers with longer résumés.

Porter has leaned into the branding: The cover of the congresswoman’s new book, I Swear, features an illustration of Porter holding a whiteboard. A two-page spread is even dedicated to explaining to readers “how to whiteboard anyone about anything.” But while the whiteboard represents some of Porter’s greatest political assets—sharp intelligence, ability to break down complex ideas into digestible bites, canny political instincts—it also highlights some of her hurdles as a representative and a candidate. Some of her colleagues in the House see Porter’s questions as a performance, intended to elevate her national profile for personal gain. “The whiteboard, man. What is that about?” said one Democratic member of Congress from California, who requested anonymity to speak candidly. “You do more legislating by keeping your head down and building relationships.”

Former Iowa Representative Cindy Axne, who served with Porter on the Financial Services Committee, joked that she had acted as Porter’s Vanna White during one hearing, by holding her whiteboard—and as such, she can confirm the prop is not merely a stunt. “Katie’s a workhorse. If she’s also able to hold a whiteboard, and get more people engaged at the same time, well, good for her,” Axne told me. “If she was just a showboat, I would be telling you, because there’s plenty of just-showboats out there. That’s not Katie. She’s getting the work done.”

But the work of Congress will jostle against the work of campaigning against formidable opponents in California. Porter and her supporters will learn whether the whiteboard is big enough for those high-profile committee hearings at the Capitol, and the intensive campaigning that a highly competitive Senate run in the nation’s most populous state will require.

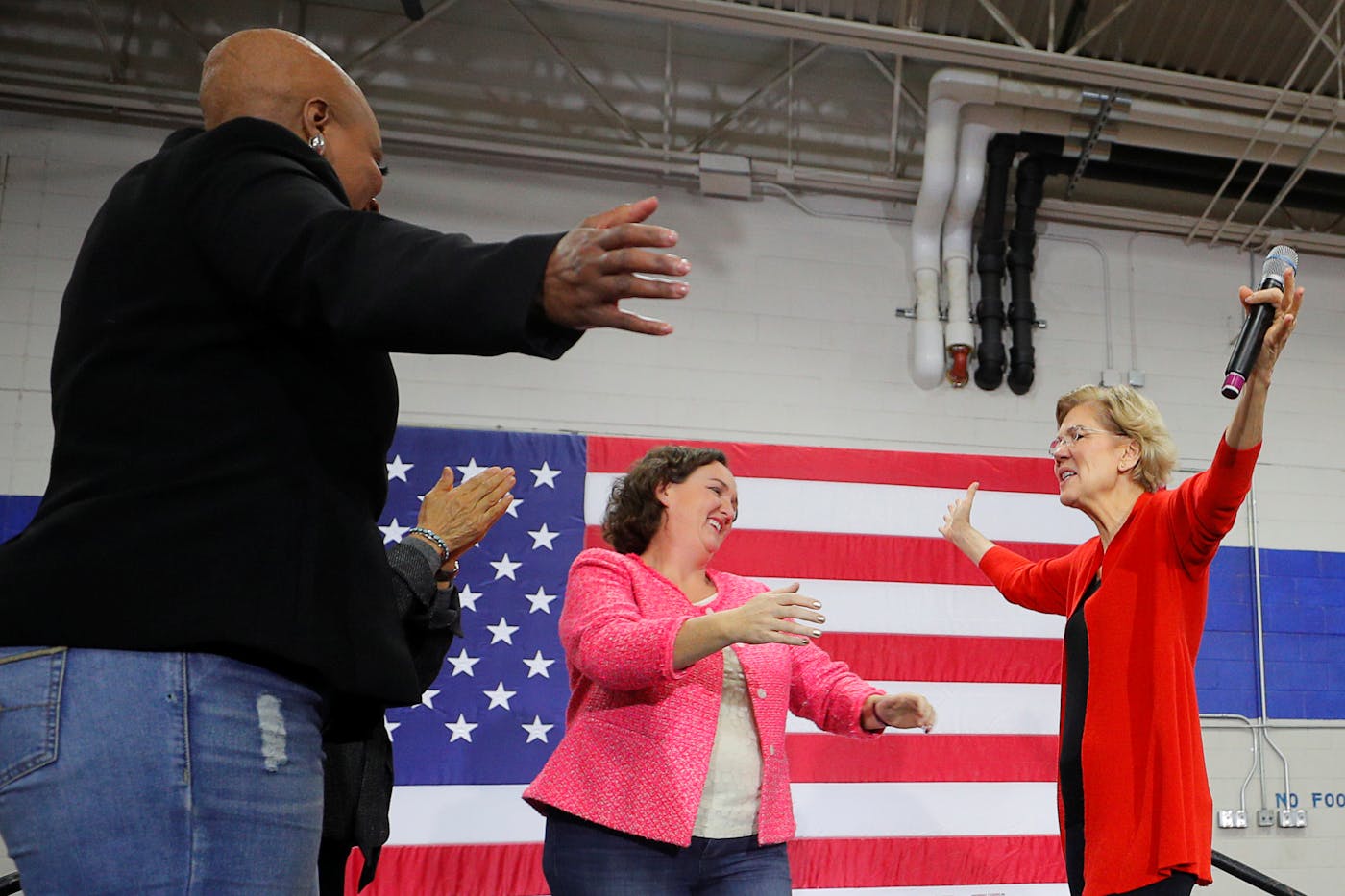

Katie Porter only has one speed, her former law professor, Elizabeth Warren, told me: “Full speed ahead.” Warren ascended from academia to the halls of Congress six years before Porter and has remained a mentor and enthusiastic supporter of her erstwhile student and research assistant. (Porter’s daughter, Betsy, is named for Warren.) Warren has endorsed Porter’s Senate campaign, quipping in a video, “We need her and her whiteboard in the United States Senate.”

Porter attended Warren’s class on bankruptcy law at Harvard Law School in fall of 2000, after reading an article in Time magazine that quoted the professor. She distinguished herself in the difficult morning class characterized by bleary-eyed students cringing at the prospect of being called upon by Warren. After giving a mediocre response, she visited Warren after class and requested that the professor call on her again so she could provide a better answer next time. “She ended up, of course, making one of the highest grades in the class,” Warren told me.

Warren chose Porter as a research assistant to aid in a project analyzing the reasons ordinary citizens file for bankruptcy. She recalled to me how Porter was greatly affected by the work, after spending time at a Boston bankruptcy court asking filers to fill out a research questionnaire.

“Katie comes back a couple of hours later and sits down across from me, and starts to talk about the people in the bankruptcy courthouse, and how awful the stories are, and how stressed and how broken many of these folks are,” Warren said. “She has a big heart for kids and her friends, but she also has a big heart for people who struggle, people who try their best and can’t always pull it together.”

Porter’s childhood in Iowa was deeply formative for the congresswoman, who saw her father go from being a farmer to working for a community bank, where his job was to collect collateral on unpaid loans—a busy profession during the 1980s farm crisis, a time when Midwestern farmers saw a precipitous drop in farmland values and a dramatic increase in foreclosures. A teenage Porter would ride along with her father as he repossessed cars and drove the repo vehicle after it was collected.

After a brief stint in private practice, during which she continued to conduct bankruptcy research, Porter entered the world of academia as a bankruptcy law professor in her own right. In her first brush with the national spotlight, a 2007 New York Times article cited Porter’s research on the questionable practices of mortgage companies benefiting from foreclosures. “I had found a problem and I had gotten front-page publicity for it. What I hadn’t done was anything to fix it,” Porter writes in her book. Her star continued to rise in the circumscribed world of bankruptcy law, as she testified before Congress and wrote articles and textbooks.

In 2011, Porter moved from the University of Iowa to the University of California, Irvine. Bob Solomon, a law professor at UC Irvine who worked alongside Porter, described her as a dedicated teacher, well-liked by her students and respected by her colleagues. The two exchanged papers, each offering feedback for the other’s research. “You will not be surprised to hear she was quite candid with her thoughts on all subjects, and was proud of it,” Solomon said with a laugh.

The year after joining Irvine, she was chosen by California Attorney General Kamala Harris to monitor the statewide implementation of a national settlement by several large banks to end predatory mortgage lending practices. Despite having no actual legal authority, Porter helped hold banks accountable for their misconduct. “My approach to oversight got noticed,” Porter writes in her book, citing newspaper articles and awards that followed her success; this taste of oversight responsibility, and the tantalizing accolades that accompanied it, augured the trend of her congressional career.

Mobilized, like many other Democratic women, by the 2016 election of Donald Trump, Porter launched her candidacy for Congress in 2017. Orange County had long been a conservative stronghold in California, but Porter spotted the crest of an impending blue wave. Warren and Harris, by now both senators, endorsed Porter almost immediately; she also earned early support from national groups like EMILY’s List. Porter prevailed in a contentious primary, whose candidates included a fellow Irvine professor, Dave Min, and she squeaked out a victory against incumbent Republican Representative Mimi Walters. (Min was later elected state senator and is now running for the congressional seat Porter will vacate, with her endorsement.) During the 2018 race, “nobody thought that we could win,” said Ada Briceño, the chair of the Democratic Party of Orange County. “And now she’s held it, and the reason why is because she has found a way to inspire her base and her constituents,” Briceño continued.

Matthew Beckmann, a professor of political science at UC Irvine and a neighbor of Porter’s, told me that he had been surprised when she decided to run for Congress. Being a well-respected and tenured law professor is a “good gig,” after all. Thus her former colleagues back home found her rapid rise in the House notable. “It’s hard as a freshman to become well-known. You go from being this kind of big-deal law professor to being a lone freshman representative. And now all of a sudden, it’s like, she’s getting famous, not for saying crazy things or doing [crazy things], but for oversight,” Beckmann said. “This is hard to get my head around. Katie from two doors down is on TV, famous for doing oversight hearings.”

Porter’s small, unassuming campaign office is tucked into a back corridor of a labyrinthine co-working space in Irvine. While this purgatory of bland professionalism is not an obvious locale for a would-be insurgent campaign, splashes of color rebelled against the drab surroundings: Porter’s eggplant-colored dress, a bright wall hanging, a few awards arrayed on small shelves, the can of Black Razzberry La Croix that Porter nursed throughout our conversation. I sat across from her desk in a chair borrowed from the adjoining conference room, feeling somewhat like a student visiting a professor during office hours.

In her book, Porter sniffs that reporters mistakenly ask why someone is running for office, when obviously the purpose of running is to get elected: It is better instead to ask a candidate why they want to be in Congress. Seeking to thwart any expectations of another milquetoast campaign interview, I posed this corrected question to Porter. On Valentine’s Day, just hours ahead of our conversation, Feinstein formally announced that she would be vacating that seat at the end of her term, lending her answer some new urgency.

“I think we need stronger fighters. I think we need people who think differently about government,” Porter replied, a ready and confident answer, if more scripted than I had hoped to prompt. “I think, having been in Congress for five years, and having brought some fresh ideas about how can we connect with people—rethinking some of the assumptions, I would say, about politics as usual. And I think we need some of that energy in the Senate,” she continued. Porter is roughly 40 years younger than Feinstein, an iconic lawmaker and the longest-serving Democrat in the Senate, who has been dogged in recent years by reports of mental decline.

Porter believes the Senate would grant her a “bigger and different platform” to conduct oversight, her great legislative passion. “You can serve on more committees, you can work more deeply, and you have a bigger staff,” she said. “The Senate really is a body that can focus better on oversight, because it’s a multiyear process to dig in on those issues.”

Porter’s transparency charmed supporters during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, when she spoke openly about the trials of working from home as a single mother, and the stresses of having her three children—one each in elementary, middle, and high school—trying to school-from-home at the same time. “People can jokingly say, ‘Tell us what you really think,’” she told me. “And I try to be honest about what I think, and I think that my constituents and voters respect that and deserve that.”

But the same candor that endears her to progressives and strikes fear in the hearts of unprepared witnesses may also occasionally alienate colleagues or sting subordinates. (Characteristic of a workplace wholly reliant on relationships, many of the House members and staffers I spoke with for this piece would offer criticism of Porter anonymously, or would only talk off the record.)

New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who served with Porter on the Financial Services Committee in their first term and continues to work alongside her on the Oversight Committee, praised Porter’s use of the whiteboard. “A major part of our job is building relationships with the public and building faith in this institution. And what she does, alongside many progressives in Congress, is really trying to breathe life into our committee process,” Ocasio-Cortez said.

Porter’s use of props in hearings occasionally grated on the Democratic chair of the Financial Services Committee, Representative Maxine Waters, a longtime member of the California delegation and an ally of former Speaker Nancy Pelosi. When Porter was not selected to serve on the Financial Services Committee in her second term, despite sending a letter to Pelosi requesting she remain, some Porter supporters blamed retaliation. Democratic leadership allies counter that Porter had not prioritized remaining on the Financial Services Committee over other committees she had selected, Oversight and Natural Resources. Two years later, Porter told me that she was “glad” she had tried to stay on the Financial Services Committee despite her lack of success, and that she had “no insight into how those final decisions were made.” “I have tremendous respect for what Maxine Waters does,” Porter said, adding that she felt prepared to lead a subcommittee in part because she “learned so much from watching Maxine run a committee.”

Still, the experience left a sour taste with some in leadership. By annoying Pelosi during the brouhaha over the Financial Services Committee, a former Democratic leadership aide told me, Porter undermined her own statewide ambitions. “Leadership is led by Pelosi, and everyone in the [California] delegation is firmly a Pelosi person,” the former aide said. While Porter’s performance in hearings is “very effective,” the aide continued, “it can be a little too much, and I think it can turn off other members.”

Pelosi, a longtime ally and mentor of Schiff, has endorsed him for the Senate, as have well over a third of members in the California delegation. Rather than weigh in directly on Porter or her campaign, Representative Jared Huffman, a California progressive who is supporting Schiff, responded to a question for this piece by noting that Schiff works “in a way that’s collaborative.” “He’s a really strong and decisive leader, but he brings others along, and he’s super respectful of others. And people just appreciate that,” Huffman said.

Even some of Porter’s congressional allies privately acknowledged to me that her talents do not lie in diplomacy with other members. Or, as Beckmann, the political science professor at UC Irvine and Porter’s neighbor, wryly observed: “If the choice is to make friends or get results, she’s going to get results.”

Porter attributes some disagreements with her colleagues to differences in generation, tax bracket, and in the competitiveness of her purple congressional district. “There’s a different voter engagement pattern, because you just are running a full-on field campaign,” Porter told me. “That’s a lot of input that we got from our constituents about how I’m doing, and what I’m doing, and what they’re concerned about, that, I think, if you don’t have a competitive race, you may not necessarily get.”

Porter’s allies in the House, particularly those elected to competitive districts in 2018, laud her willingness to challenge the status quo. “I really honestly don’t even know how many times I’ve seen Katie Porter push back against leadership, because it’s been so many. And it’s not to cause problems, it’s to move an agenda forward that she’s right about, one that’s more focused on working-class families in this country,” said Axne, who narrowly lost reelection in 2022.

Virginia Representative Abigail Spanberger, a friend who also flipped a red district in 2018, argued that Porter came to Congress with a sense of urgency that countered the established method of legislating preferred by leadership. “You have such a strong, sassy woman who’s so incredibly smart and doesn’t do things to hide it, right? [She] doesn’t do the one hundred ‘thank-yous’ at the beginning of a meeting,” Spanberger said. “People are like, ‘No, no, no, we want you here, we just don’t always want to hear from you.’ And people like Katie were like, ‘Yeah, but I’ve got a lot to say, and I’m going to say it.’”

Porter’s high-octane, no-bullshit style also characterizes the atmosphere of her office: The congresswoman has a widely known reputation as a difficult and an overly demanding boss. In late December, the Twitter and Instagram account Dear White Staffers, which chronicles allegations of hostile work environments from current and former Hill aides, posted several anonymous messages from alleged former Porter staffers highlighting instances of inappropriate or even abusive behavior. (In 2020, Porter had the second-highest staff turnover rate in the House.)

One of those staffers, Sasha Georgiades, has gone on the record about her experiences as a fellow in Porter’s district office. Porter castigated Georgiades over Signal for not testing immediately for Covid-19 when she began to feel unwell and blamed her own positive diagnosis on Georgiades. Georgiades, a veteran who had been employed through the Wounded Warrior Program, insists that she did not know at the time she came to the office that she had the virus, and that she followed protocol after testing positive. Nonetheless, she was banned from returning to the district office for the remainder of her fellowship.

Georgiades, who now works as a contractor (but would not specify in which industry), told me that she witnessed multiple instances of Porter being short-tempered toward her aides. “If you treat your staff like that, if you can be so cruel to people that you work with every day and that do nothing but give their time and their dedication and their effort—and literally sweat, blood, and tears—and you can still be that dismissive to them, then how are you going to act now that you’re [running for] the Senate?” Georgiades said, arguing that Porter had “lost what the purpose is of why she’s actually there.”

She continued: “I just think she got a taste of what it was like to be more than just another person in Orange County. And she wants to stay more than another person in Orange County.” (This was not the first time that texts sent by Porter have come under media scrutiny; she berated the mayor of Irvine over text after the man Porter was living with was arrested for allegedly punching a Trump supporter at a town hall event.)

For her part, Porter told me that she had maintained protocol. “We have office policies for a reason,” she said. “When people break policies, they can’t come back to the office and put others at risk. I don’t think I’d be being good to my employees if I took a different attitude.” Porter also attributed “most of what you’ve seen and heard” to the growing pains of her first term in office: “I don’t think any of us were having fun.”

Porter discusses her relationship with staffers in her book, a sort of mutual codependency. One chapter describes a frenetic interaction between Porter and her staffers early in her first term, after she failed to speak quickly enough to complete her thoughts in a one-minute speech on the House floor. “I trusted these staffers, and they let me down,” Porter writes. “I was always going to be the one standing there doing it wrong when they made mistakes.”

Speaking from the perspective of herself and several staffers—Porter wrote the recollected conversation but consulted with participants for accuracy—the congresswoman describes how her staff figured out how many words she spoke per minute, and therefore how to adjust her remarks. After much agita, Porter was given a fresh copy of the speech, and was able to deliver it within a five-minute time frame the next day.

Porter told me that the choice of anecdote was deliberate. “I’m certain I could have picked a moment in which, like, I was the hero. But to do that is to suggest that I’m not saved by my staff a million thousand times a day in a bunch of different ways, by their dedication, their hard work,” Porter told me. “I think that’s what hard work looks like. That’s what grit looks like, is being able to say, ‘That was not it.’ Like, what did we do wrong? How do we fix it?”

Her staff can also be on the receiving end of some of Porter’s more acerbic zingers. One two-page spread in I Swear outlines various “Katie-isms,” that is, ways to respond to mistakes or shortcomings by aides. When a staffer spills Diet Dr Pepper on Porter’s dress, for example, the reactive Katie-ism would be: “It’s a good thing for you that I believe in gun violence prevention.” Porter told me that she had sourced that section by asking her staff to brainstorm their recollections of Katie-isms, and that “the ride is bumpy,” but her aides know “we’re in it together.” She added: “I do have a sense of humor. And do I think humor always lands? Well, no. That’s partly why it’s humor, right?”

After narrowly defeating Walters in the blue wave election of 2018, Porter earned the distinction of a “frontline” Democrat, in the vernacular of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee: an endangered incumbent in a hotly contested seat. Porter, who has served as deputy chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, is also frequently cited as an unapologetic progressive who could nonetheless win in a swing district without compromising her ideals.

Orange County, Ronald Reagan once joked, is where “the good Republicans go before they die.” But the political winds have changed in recent decades, and those good Republicans are now outnumbered by registered Democrats. Porter’s district includes a large portion of the county, encompassing multiple demographic interests: wealthy beachfront conservatives in Newport Beach and Huntington Beach and wealthy academic progressives in Irvine, with a significant contingent of Asian American voters and a population of university students.

Democrats in the district say that, despite her brief career in the House, she has revitalized local party efforts. “It makes a world of a difference when you have a candidate like Katie at the top of the ticket,” said Cassius Rutherford, the chair of the Costa Mesa Democratic Club, in a town in Porter’s district. Volunteer enthusiasm around Porter’s campaign benefited candidates for citywide office.

Ada Briceño, the Democratic Party of Orange County chair, also told me that Porter “helped us build a bench” by supporting and campaigning for local women candidates who won their elections in 2022. “It takes a lot of knocking on doors in order to get across that finish line. And that is something that is really understood by the congresswoman,” Briceño said. “She has a very strong field and ground game.”

That ground game was sorely tested in 2022, after Porter ran for a new, redistricted seat that now included the more conservative Newport Beach and Huntington Beach. Porter defeated Republican Scott Baugh by only 3 percentage points, and she spent roughly $28 million to ensure that hard-fought victory. Baugh received significant support from two Republican-aligned super PACs, the Congressional Leadership Fund and Club for Growth, which hammered Porter on inflation and crime. One ad by Club for Growth even employed Porter’s signature prop, featuring women holding their own whiteboards challenging her economic record.

One potential benefit of launching her Senate campaign in January is having the extra time to recoup those spent funds; when she announced, Porter had roughly $7 million in her coffers, compared to $20 million in cash on hand for Schiff. Many of Porter’s supporters in the district understand her rationale for seeking higher office: “It’s not like Katie’s going to go from representing us in Congress to the thin air. She’s actually going to be able to represent us far more effectively in the Senate,” Rutherford said.

Porter insisted to me that she will not abandon the base that she has so successfully galvanized. Moreover, those talents for fieldwork will be brought to task in races across the state, not just in Orange County: “By really running a robust campaign, I will help turn out people in the primary and the general, and that will help us win,” Porter said.

“You hear people say, ‘Oh, it’ll be nice to run every six years,’ and I may be on the ballot once every six years, but the ballots go out every two. And that is not something I will forget,” Porter told me later in our conversation. “I intend to be on the ground every two years, making a big difference in California and around the country.”

Porter has already used her progressive clout to support other candidates. Representative Robert Garcia, a freshman California lawmaker whose district borders Porter’s, noted that she was the first member of Congress to endorse him. “Early on, we talked a lot about her trailblazing around not taking corporate PAC money,” said Garcia, who did not take corporate PAC money in his own campaign. “She gave great advice, and I respect her greatly for that.” Porter’s own PAC, Truth to Power, supports candidates who she believes will stand up to special interests.

Porter has been considered a prospective Senate candidate for years; she was floated as a potential choice to fill Harris’s vacated seat in 2021 when she became vice president. Porter declined to run against incumbent Senator Alex Padilla, the eventual choice, in 2022, but anyone paying attention to California politics could intuit that Porter would be interested in a Senate bid.

Her entry into the Senate race before Feinstein’s official announcement rankled some who argued that the senator should get to retire on her own terms. (Feinstein released statements welcoming Porter’s and Schiff’s candidacies before she formally announced she would step down at the end of her term.) But Porter defended her timing, telling me that she needed to jump into the race as quickly as possible in order to reach potential supporters. “A shadow campaign, a whisper campaign, doesn’t let you connect with voters,” Porter told me. “I think the most respectful thing to do with regard to Senator Feinstein was to let her know that I was running.”

The grassroots network that Porter has built nationally, seen in microcosm in the volunteer enthusiasm in her Orange County community, was quick to activate. The day after her announcement, Porter’s campaign reported that she had raised roughly $1.3 million in small-dollar donations in the first 24 hours. A Quinnipiac poll released at the beginning of March showed that 39 percent of voters would be “enthusiastic” if Porter became the next senator for California, compared to 35 percent for Schiff and 34 percent for Lee. “This Senate primary will be good for California, will be good for democracy in California,” Porter said, rapping her fist on her desk as she spoke. “I think we can have a primary that creates momentum to help our next senator accomplish those downstream and across-the-country political effects.”

As Porter is quick to note, she is one of only a handful of single moms of school-age kids serving in the House. Motherhood is intrinsic to Porter’s behavior as a lawmaker and a candidate for Senate: It is both key to her appeal, lending authenticity to her public persona, and a daily reality.

Porter engenders a certain excitement from local Democrats, and especially from women, said Luette Forrest, a retired veterinarian who worked at UC Irvine and has been involved with Democratic politics in the area for decades. Part of that popularity stems from that appearance of authenticity; she fully embodies the persona of a mom with a minivan because she is a mom with a minivan. “She’s a regular human being. She’s as advertised, as far as I can tell,” Forrest said. “She’s not living a double life. People see her in the grocery store.”

Although some Democratic members may privately feel as if Porter is patronizing in her admonitions to colleagues about the stresses of inflation or everyday costs, her perspective comes from experience. “When I say this or that about the price of groceries, I’m the only one there is. So we know who gets the groceries in my house; it’s me. We know who figures out the childcare in my house; it’s me,” Porter said.

The House is hardly designed to accommodate parents of young children, and particularly not single parents. Porter expressed frustration with late vote times and inconsistent committee schedules, arguing in favor of block schedules for hearings. (Porter took particular advantage of the proxy voting that was in place from 2020 through January 2023.) “If we want a Congress that looks more like America, then we have to think about creating a workplace that accommodates different kinds of people and workers,” Porter said.

Toward the end of her book, Porter recalls how her frankness with a reporter earned her a distinction in a 2020 profile in Elle magazine: “Being Everywoman was described as my superpower.” With Everywoman superpower, however, comes Everywoman responsibility. Being a single parent is difficult, even with an annual salary of $174,000 and university-provided housing; Porter is currently on leave from UC Irvine, and her living situation has earned her criticism from right-wing outlets. Being a single mom and trying to supervise her children from almost 3,000 miles away, spending 14 to 18 hours per week on a plane when the House is in session, make full-time parenting incredibly difficult. Then there is the balance of emotional labor, attending to the needs of children and of hundreds of thousands of constituents.

“My kids are my toughest constituents. They’re also my kids. So they feel free to chime in on everything from, ‘You forgot to buy the Cinnamon Toast Crunch, and this is the third time I’ve reminded you,’ to ‘Mom, why would you ever vote for the NDAA?’” Porter told me, adding that she did not, in fact, vote in favor of the recent National Defense Authorization Act.

Porter has survived difficult primary and general elections before, but never on a statewide scale. The race between Porter, Schiff, and Lee, as well as any other candidate who hops in, will involve major political players and PACs, inviting new levels of scrutiny over more than a year of campaigning. (One of the groups that supported Porter’s 2018 campaign is now assisting a pro-Schiff PAC.) California’s jungle primary, in which the top two vote-getters advance—a free-for-all hellscape, if you will—isn’t until June 2024.

Authenticity in politics can be a trap, particularly for women; the more one tries to come across as genuine, the less real it feels. The one-liners of an exhausted but effective mother can occasionally seem like a shield—and at worst a calculation—when that single mom with a minivan is also seeking an incredibly powerful position in the nation’s most populous state. “Ambition in political life is a constant and a given. The question is, what kinds of public ambitions are your personal ambitions linked to?” said Raskin, who has not made an endorsement in the California Senate race. “In Katie’s case, her personal ambitions are connected to a belief that the government has got to be in service of a cognizable public interest.”

Like words scribbled on a whiteboard, Porter’s identity has been clearly telegraphed. Voters now have more than a year to decide whether the mom in a minivan actually embodies the image she has cultivated—and, if she does, whether it is enough.

“Take or leave me,” Porter writes in her book, “but know me.”