Seven years ago, Florida Senator Marco Rubio alleged that then-candidate Donald Trump had “small hands” and strongly implied the same was true about other parts of Trump’s anatomy. Trump insisted to the American people during a presidential debate that “there’s no problem, I guarantee you.” Now that historic moment is going before the Supreme Court of the United States.

Fortunately for everyone involved, the justices won’t be weighing in on the factual dispute between Trump and Rubio. Instead, they agreed to take up a case on whether someone can trademark a T-shirt that references the exchange. In Vidal v. Elster, the court will decide whether the First Amendment requires the Patent and Trademark Office to register trademarks that criticize a public figure or a government official.

The Lanham Act of 1946 is the flagship federal law for trademarks. It lays out in detail what can and can’t be registered with the PTO. Most of the restrictions are commercial in nature: Marks can’t be registered, for example, if they could lead to confusion with a preexisting product or company, either through intentional fraud or accidental resemblance. If I tried to open an auto repair shop and name it Ford’s Motors, the PTO would probably reject my attempts to register that name as a trademark.

One of the act’s other provisions, known as Section 1502(c), also forbids the PTO from registering a mark that “consists of or comprises a name, portrait, or signature identifying a particular living individual except by his written consent.” It also applies the same restrictions to marks that include the name, portrait, or signature of a deceased president of the United States “during the life of his widow, if any, except by the written consent of the widow.” Congress added it in the original act to, in its view, prevent unscrupulous merchants from using the presidents’ good names to hawk merchandise.

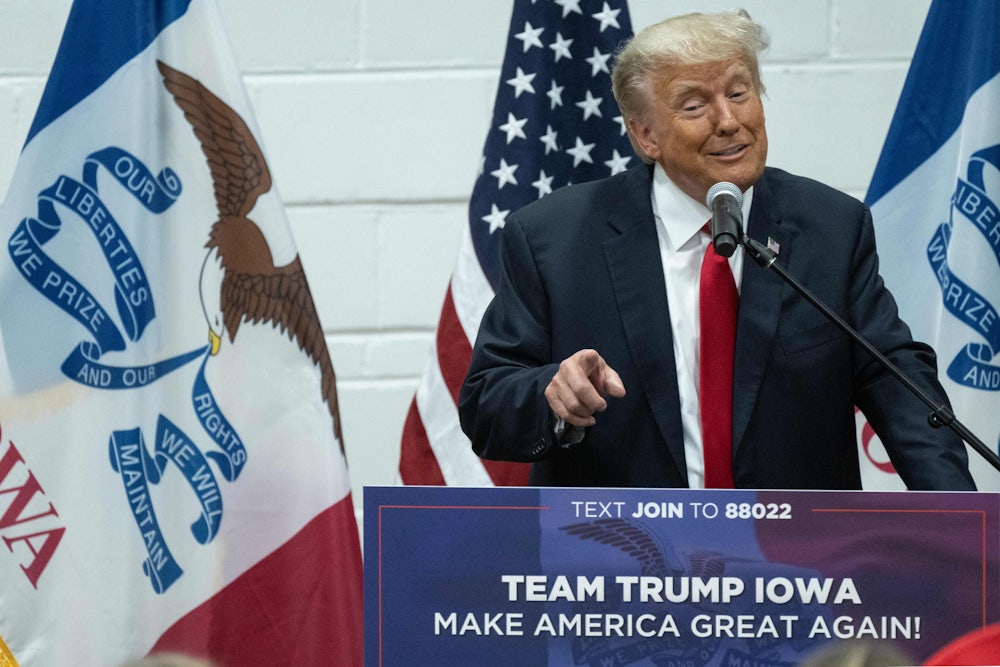

That caused problems for Steve Elster when he tried to register the mark “Trump Too Small.” According to his brief for the justices, the term “criticizes Trump by using a double entendre, invoking a memorable exchange from a Republican presidential primary debate, while also expressing Elster’s view about ‘the smallness of Donald Trump’s overall approach to governing as president of the United States.’” On his website, Elster sells T-shirts that say “Trump Too Small” above a hand gesture for smallness on the front, with a bullet-point list of various policies on the back that Elster describes collectively with the phrase “Trump’s Package is Too Small.”

This is not exactly Jonathan Swift. But while the PTO does not judge based on wit, it does judge based on the Lanham Act. A PTO examiner denied Elster’s registration of the mark based on 1502(c)’s ban on using the names of living persons. (While it is not relevant at the moment, the carve-out for dead presidents while their spouse is still living would also likely prohibit future registration for decades to come.) Elster appealed the examiner’s decision to an internal PTO review board, which also ruled against him. He argued that the PTO could not deny the mark without infringing upon his First Amendment rights.

Elster then appealed the board’s decision to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, a special federal appellate court that hears, among other things, patent and trademark appeals. This time he found a more favorable audience. A three-judge panel in the Federal Circuit ruled that denying registration infringed upon the First Amendment, especially because the mark in question involved criticism of a public figure and now-former elected official. The panel also rejected the government’s claims that the restriction was justified under a right to privacy or a right to publicity. In the latter case, the panel noted, there was “no plausible claim” that anyone could think using Trump’s name in the mark meant that Trump had endorsed it.

The Justice Department then asked the Supreme Court to intervene and overturn the Federal Circuit’s approach. “Because living persons have ‘valuable’ rights in their own names, the government has an interest in not promoting or associating itself with marks that ‘appropriate or commercially exploit’ a living person’s name ‘without his consent,’” the department argued in its petition for review, quoting from past court rulings on the matter. “And on the other side of the balance, [Elster’s] unquestioned First Amendment right to criticize the former president does not entitle him to enhanced mechanisms for enforcing property rights in another person’s name.”

Elster, in his own brief for the court, noted that the Supreme Court has recently ruled that trademarks carry First Amendment weight as expressive speech. The justices overturned a provision of the act that banned the registration of marks that disparage members of a racial or ethnic group in the 2017 case Matal v. Tam. The Slants, an Asian American band that sought to reclaim the slur, successfully persuaded the justices that trademarks are private speech, not government speech, meaning that restrictions on them can be protected by the First Amendment. Two years later, in Iancu v. Brunetti, the court also struck down the Lanham Act’s ban on registering marks that are “immoral and scandalous” on similar grounds.

Those cases involved government restrictions on specific viewpoints. The First Amendment is typically unforgiving where such restrictions are involved. But the justices explicitly left open the question of how far the government could go with viewpoint-neutral restrictions that only pertain to certain types of content. While the dispute in question focuses on Trump, Section 1502(c) would have the same effect if it targeted any other living person instead of him, including Democratic or other Republican presidents.

To that end, the Justice Department also emphasized that lack of registration doesn’t mean that the mark can’t be used in commerce. “When registration is refused because a mark consists of or comprises a name identifying a particular living individual without his written consent, no speech is being restricted; no one is being punished,” the department claimed in its brief for the court. And while an unregistered mark would lack some of the legal protections against infringement that registered marks have, the Justice Department argued that Section 1502(c) is merely a “condition on a government benefit” and therefore doesn’t trigger the First Amendment.

That last point may be somewhat difficult to make before a court that has invalidated other provisions in the Lanham Act in recent years on First Amendment grounds. If Elster prevails, on the other hand, Americans will be able to register trademarks that mock or disparage other living people without their consent, with all the legal privileges that registration entails. While the case won’t be heard or decided until after the court’s next term begins in January, a Lanham Act case being heard this term could give an indication of how willing it might be to side with Elster. A case involving Jack Daniel’s and satirical chew toys for dogs will test how trademark law applies to parody. If the justices don’t find that line of products to be funny, Elster might find their patience with his joke to be, well, too small.