Originalist justices now hold a majority of seats on the Supreme Court. As originalists, these justices believe that when the Constitution was written, the informed public understood the meaning of its vague clauses; and they believe that that meaning, as a kind of fundamentalist Scripture, must be binding for all time unless changed through the extremely arduous Article V amendment process.

Originalism began in the 1970s as a conservative response to the constitutional reforms of the Warren court, as a way to restrain liberal judicial activism. Yet today, with conservatives in firm control of the Supreme Court, originalism has come to support a turbocharged judicial activism of the right.

On a wide array of major legal issues—religious liberty, gun control, presidential power, sovereign immunity—the court’s conservative originalist justices are transforming constitutional law through opinions that claim to bring the Constitution back to what it meant when adopted. Yet all these opinions reach their result through flawed historical investigations. They are examples of what is disparagingly called “law office history.” They cherry-pick evidence, give their subject incomplete consideration, are out of touch with the findings of recent historical scholarship, and reach conclusions that just happen to coincide with the writers’ preestablished political and social views.

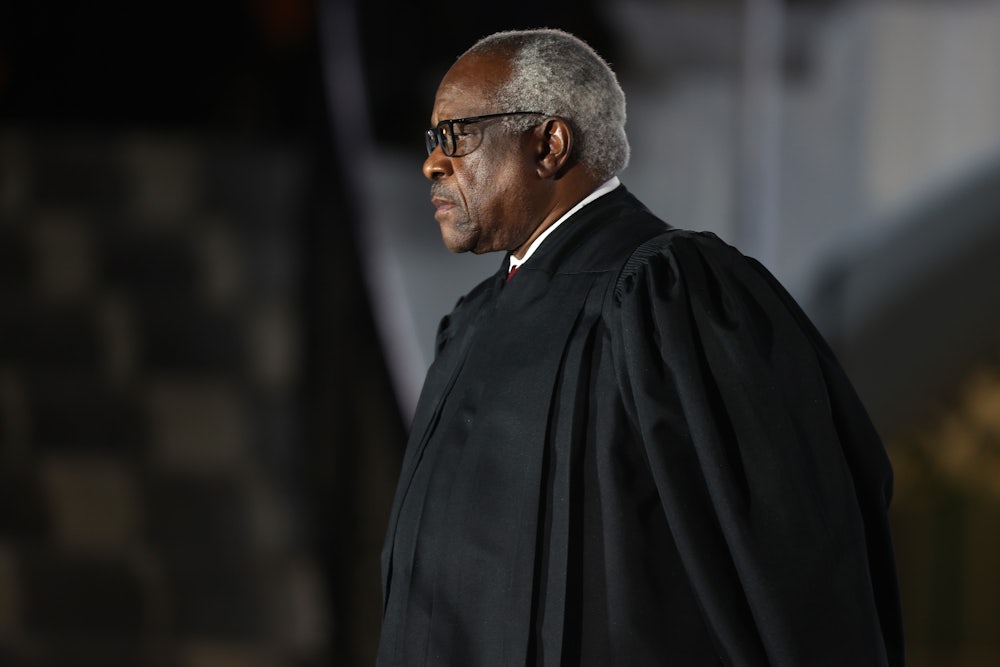

Justice Clarence Thomas’s concurring opinion in the Harvard and University of North Carolina affirmative action case well illustrates the shortcomings of originalist jurisprudence. Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority ruling was not based in this case on originalist assumptions but on his long-held, wrongheaded belief that race has disappeared as an important contemporary factor in American life and therefore in jurisprudence. So it falls to Thomas to uphold the originalist banner here.

Thomas’s opinion disagrees with the trend of recent studies on the intent of the proponents of the Reconstruction amendments, which was to fundamentally restructure American society to include fully the country’s Black citizens. This current scholarship supports an “anti-subordination” understanding of those amendments. It says the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to forbid laws that harmed Blacks but not laws that helped them. Thomas mentions this scholarship, but immediately dismisses it—a whole generation of scholarship—as a “vogue” that “lacks any basis in the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Thomas wins his argument not by trenchant critique but by cavalier fiat.

The opinion is also remarkably ahistorical. With five committed originalists on the court, counsel on both sides of the case expected an originalist view of the issue to be decisive, and they prepared accordingly. What gave proponents of affirmative action hope for success was that throughout the period when Congress and the states were drafting and ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress and a number of states were passing statutes giving all manner of special benefits and protections to “heads of families of the African race,” to “destitute colored women and children,” to “colored soldiers,” to “colored children,” and to millions of “freedmen.” One example of this legislative activity is Congress’s 1866 law providing special educational opportunities to Black, but not white, soldiers by mandating that chaplains assigned to Black regiments provide their troops with “instruction … in the common English branches of education.” Another example is an Illinois statute imposing a fine on “any person who shall by threats, menace, or intimidation, prevent any colored child entitled to attend a public school in this state from attending such school.” In short, if Congress and state legislatures at the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment enacted what were effectively affirmative action statutes, how could it possibly be said that affirmative action was not permitted by the Fourteenth Amendment?

Thomas sweeps all this legislative activity aside by saying such statutes are compatible with modern-day Fourteenth Amendment law, which allows race-based remedies for the victims of proven racial discrimination. Under modern Fourteenth Amendment law, race-conscious laws are permitted if they can be shown to be strictly necessary to promote a compelling governmental purpose. This is known as the test of strict scrutiny. Under the court’s precedents, providing race-based remedies for a proven case of racial discrimination is an example of a race-conscious governmental action that meets strict scrutiny.

Let us put aside whether Thomas fully established, rather than simply assumed, that these post–Civil War affirmative action laws met all the narrow tailoring requirements of modern strict scrutiny doctrine. My point is that requiring affirmative action laws to pass the test of strict scrutiny is anachronistic. The doctrine of strict scrutiny is a late-twentieth-century innovation in constitutional law. Throughout the nineteenth century, laws had only to pass a test of reasonableness. In Fourteenth Amendment litigation, subjecting affirmative action laws to strict scrutiny rather than the more permissive rule of reasonableness cannot be part of the amendment’s “original meaning” because no one at the time had ever thought of the idea. The only exception was law affecting civil rights where equality was required. Civil rights, however, were a very limited group. As stated in the 1866 Civil Rights Act, they were the basic right to own, inherit, and sell property; to make and enforce contracts; and to sue and give evidence in court. Outside of those limited area of civil rights, throughout the nineteenth century, color-conscious laws only had to be reasonable to be upheld. Indeed, all government regulation of life, liberty, or property—outside the area of civil rights—was valid if reasonable, and invalid if unreasonable. By imposing the test of strict scrutiny on college affirmative action programs, Thomas is importing twentieth-century law into his understanding of the nineteenth century. Some “originalism”!

Thomas’s imposing the test of strict scrutiny to judge contemporary affirmative action law is also risible because, in stark contrast, he refuses to permit the application of strict scrutiny to cases involving the Second Amendment where, because public safety and human life are involved, there frequently is an obviously compelling governmental interest. Thomas’s originalism here seems clearly jerry-rigged to achieve the desired outcome.

Thomas’s opinion also is an incomplete history. Thomas never considers that before, during, and after the period when Congress was adopting the Fourteenth Amendment, it was also adopting laws that we would regard as racially discriminatory. Before the Civil War, Black children were excluded from Washington, D.C., public schools. In acts of racial progress, the Civil War and Reconstruction-era Congresses allowed Black children into Washington D.C. public schools, but only in segregated classes. The same Congresses allowed Black men into some (but not all) branches of the armed forces, but only in segregated units. And they also expanded the nation’s naturalization law to include not only white immigrants but also “people of African descent.” This expansion continued to exclude people of Asian descent from the naturalization process.

These unmentioned facts of history are central—and it is essential for Thomas to have ignored them to make his argument—because they cannot be explained away as compatible with current Fourteenth Amendment law. The relevance of these discriminatory laws is further highlighted by Justice Thomas’s insistence that the Fourteenth Amendment’s equality principle was made binding on the federal government by the amendment’s grant of citizenship to everyone born in the country.

What does Congress’s segregating public schools and the armed forces say about the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equality principle? I suggest it indicates that when the Fourteenth Amendment was written, color-conscious laws affecting education and the armed forces only had to be reasonable to be upheld. They did not have to survive the far more stringent test of strict scrutiny, which Thomas insists on imposing here—though, of course, not when it comes to gun control.

It is a telling weakness of Thomas’s opinion that punctures another pretension of originalist jurisprudence that none of the court’s other originalist justices joined his opinion. Instead, they all signed onto Roberts’s non-originalist opinion. Especially in light of the decades-long failure of originalist justices to write originalist opinions in affirmative action cases, their failure to join Thomas’s opinion is fatal to originalism’s claim that it is the only jurisprudence a jurist should employ in interpreting the Constitution.

If the court’s other dedicated originalists had joined Thomas’s opinion rather than Roberts’s, it would have made Thomas’s views binding precedent. Because of the opinion’s historical anachronisms, distortions, and omissions, it would have produced a law of the land contrary to what the Civil War generation anticipated but one that clearly reflected Justice Thomas’s own political, social, and constitutional views.

Thomas’s concurrence discloses something

other than the intentions and expectations of the Framers and ratifiers of the

Civil War amendments. Unintentionally, Thomas has illustrated how originalism

on the Supreme Court is nothing more than an instrument for justices to read

their own views into the Constitution and infuse their politics into

constitutional interpretation.