It’s been more than two years since the Supreme Court opened a new frontier for gun laws. In New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, the court laid out a far more restrictive test for determining whether such laws violate the individual right to bear arms that the justices previously found in the Second Amendment. I’ve chronicled time and time again how judges have tried to apply that test to existing laws, sometimes with far-reaching implications.

Earlier this month, a federal judge in New York ruled that simply possessing a gun in public no longer amounts to probable cause for an arrest in that state. The decision is one of the first to apply Bruen to how police officers carry out searches and arrests—a sign of how much the Supreme Court’s ruling has changed the legal landscape when it comes to guns in American life.

In February 2023, NYPD officers encountered Robert Homer on Guy R. Brewer Boulevard, near the border of the Rochdale neighborhood in Queens. A group of officers, using the city’s ARGUS surveillance camera network, observed him sitting in the driver’s seat of a silver van. One of the officers saw Homer put what appeared to be a black handgun into one of his pockets while in the van, go to a nearby deli to get something to eat, and return to the van. After his return, officers arrested him and found a handgun in his pocket. Court documents do not say whether he was able to eat his meal first.

After his arrest, federal prosecutors charged Homer with violating a federal law that bans people with felony convictions from owning firearms. Critically, however, the officers were unaware that Homer had a previous felony conviction prior to arresting him. Instead, their justification for making the arrest—what is known as “probable cause” in court—revolved around his simple possession of a firearm. The arresting officer additionally told the court that he thought Homer lacked proper “firearm discipline” and that he was in what the police described as a “high-crime area.”

Homer’s lawyers saw things differently. In their telling, their client was minding his own business when he was arrested for no reason. “Neither [the arresting officer] nor any of the [other] NYPD officers who arrived on scene witnessed Mr. Homer do anything suspicious, much less anything that would give rise to probable cause to arrest Mr. Homer,” they told the court. “Mr. Homer was simply sitting in the driver’s seat of a car when the arresting officers arrived on scene and immediately pulled him from the car and placed him under arrest.”

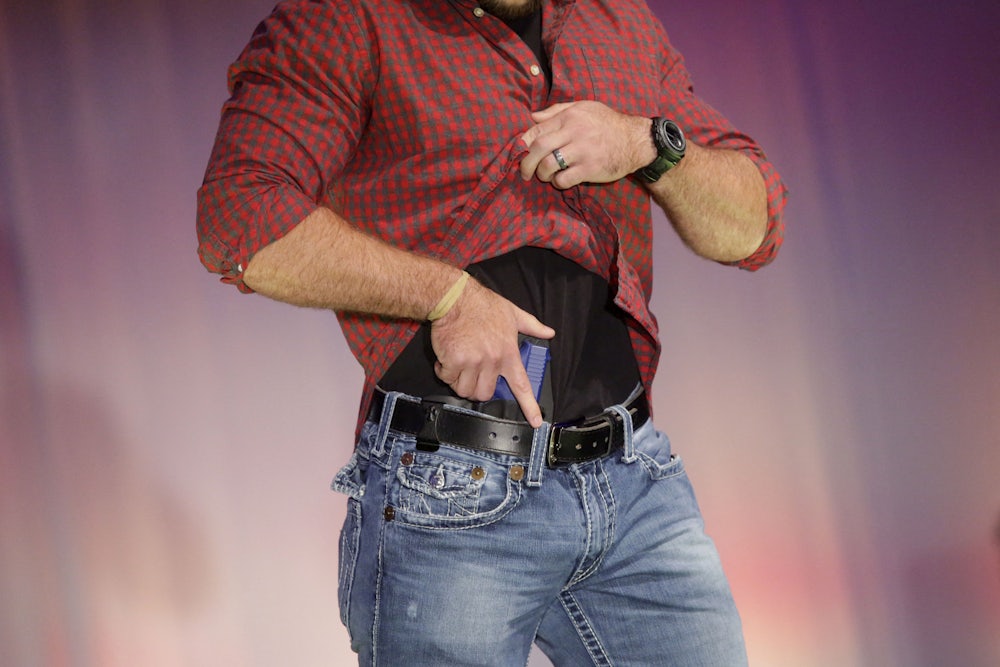

Accordingly, his lawyers filed a motion to suppress any evidence obtained as a result of Homer’s arrest, including the discovered firearm. They claimed that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Bruen and the subsequent expansion of New York’s concealed-carry laws changed the calculus for when a person’s behavior becomes suspicious enough for an arrest. “Even assuming the unidentified NYPD officer observed Mr. Homer on live video surveillance briefly holding what resembled a firearm, that observation is not sufficient to establish probable cause to believe that Mr. Homer committed a crime,” Homer’s lawyers told the court.

Federal prosecutors pushed back by arguing that the sum of events met the probable-cause threshold. Homer was “holding a firearm in his hand unsecured while in a car with other people, in a high-crime area and in a car recognized as connected to a violent gang,” prosecutors said in court filings. (As the court later noted, the officers couldn’t see the license plate and therefore only knew it as a silver van, of which there are many in New York City.) They also faulted Homer for what they described as “faulty gun discipline” based on how Homer handled the gun. “This was not the mark of a licensed gun owner,” prosecutors claimed. Bruen, in their view, “does not affect the probable cause calculus in this case whatsoever.”

The district court thought otherwise. “In the pre-Bruen world, the court agrees that a police officer likely would have had probable cause to arrest someone that the officer observed in a high crime area at night with a firearm,” Judge Nicholas G. Garaufis wrote in the decision. Since concealed-carry licenses were so rare in New York before Bruen, and so few people had them, officers could reasonably conclude that someone they spotted with a gun in those circumstances didn’t have a license.

In Bruen, the Supreme Court’s justices articulated an expansive approach to the Second Amendment. Restrictions that do not pass Bruen’s new history-and-tradition test, which only allows courts to uphold gun laws if they have a founding-era analogue, are now invalid. Lower courts have spent the last two years trying to decide which laws survive under the new test, sometimes reaching wildly different conclusions. The Supreme Court is already mulling a follow-up case about whether Bruen invalidated a federal law that bars domestic abusers from owning a gun.

After Bruen came down and New York rewrote its gun laws to match it, however, that calculus had changed. “For the purposes of this inquiry, the practical effect of [the amendment] is to make gun licenses for public carry significantly more accessible,” Judge Garaufis explained. “The licensing exception that police could have reasonably disregarded before Bruen was substantially broadened so that police can no longer reasonably assess whether a person was committing a crime without taking the exception into account.” As a result, he ordered the evidence to be suppressed.

The court’s ruling was bounded by the practical steps that the officers could have taken to make a more lawful arrest. For one thing, Garaufis noted, the cops could have tried to actually identify Homer before arresting him. That would have allowed them to discover his prior felony conviction, which in turn would have provided probable cause. They also could have performed what’s known as a stop and frisk to find the gun and check for a license instead of jumping straight to an arrest. Since the officers only arrested Homer for the mere fact of having a gun, however, they couldn’t use any evidence obtained from the arrest to prosecute him.

Garaufis is not the first judge to conclude that Bruen has changed the calculus for when cops can arrest people for having guns. In an evidentiary ruling in a federal gun-related case last year, a federal court in Connecticut reached a similar conclusion. That case also involved an armed defendant who was arrested before officers determined he had a felony conviction. “Consequently, by the time of the second search, the officers did not have enough facts to support probable cause,” Judge Stefan Underhill wrote, citing Bruen. “That is because an individual cannot be presumed to be carrying a firearm unlawfully simply because of their possession of a firearm.” The motion to suppress in that case ultimately failed for unrelated reasons.

Bruen did not technically address police interactions like the one Homer experienced, so it is unclear whether other courts will adopt the same reasoning. But one of the friend of the court briefs in Bruen did discuss how New York’s gun laws affected policing strategies, particularly in New York City. The brief, filed by a coalition of legal aid and public defender groups in the state, told the justices that the pre-Bruen law led to draconian outcomes for otherwise law-abiding citizens.

“We routinely see people charged with a violent felony for simply possessing a firearm outside of the home, a crime only because they had not gotten a license beforehand,” they claimed. They also noted that the NYPD had a history of predominantly enforcing those laws against communities of color in New York City, particularly among Black and Hispanic New Yorkers. “According to NYPD arrest data, in 2020, 96 percent of arrests made for gun possession ... in New York City were of Black or Latino people,” they told the justices. “This percentage has been above 90 percent for 13 consecutive years.”

One can also understand how the Homer decision flows from the court’s vision of gun rights in Bruen. By hewing to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century gun restrictions, it reflects an America where owning and carrying a gun were part of everyday life, either for self-defense or for survival in the early republic. A world in which the Second Amendment is no longer a “second-class right,” as Justice Clarence Thomas lamented before he wrote Bruen, is likely a world where seeing someone with a gun in public is no longer a sign of imminent criminal activity. But as the events in the Homer case demonstrate, it’s far from clear if everyone is going to see this the same way.