“I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters, OK?” Donald Trump infamously told an audience on the campaign trail in 2016, referring to his supporters’ enthusiasm. Nearly a decade later, he wants to ensure that he wouldn’t face a criminal prosecution for it, either. Those efforts hit a setback this week as the Supreme Court narrowly declined the opportunity to provide the legal relief he sought—at least for now.

The president-elect was sentenced Friday morning in his New York hush-money criminal case. Like most defendants, the president-elect would have preferred not to be sentenced at all. Unlike most defendants, he enjoys some enviable privileges, one of which is that he gets to ask the Supreme Court to step in and save him from further interactions with the criminal justice system.

In a stay application filed on Wednesday, Trump’s lawyers asked the justices to simply halt the proceedings on presidential-immunity grounds, which did not exist before the Supreme Court invented them out of whole cloth last year in Trump v. United States. Trump’s legal team argued that the high court must step in to “prevent grave injustice and harm to the institution of the presidency and the operations of the federal government.”

That is hyperbole, to say the least. Judge Juan Merchan, the New York judge presiding over the case, had already said in court documents that he would not send Trump to prison—an obviously unfeasible option when Trump is set to be inaugurated as president 10 days later. On Friday, he made good on his word, sentencing the president-elect to “unconditional discharge,” meaning that he would face no punishment in the form of imprisonment, probation, or fines. Merchan said on Friday that it was the “only lawful sentence” he could hand down, given Trump’s imminent return to the White House.

Knowing that this would be the case, the Supreme Court ruled against Trump’s stay request on Thursday night in a 5–4 vote. “First, the alleged evidentiary violations at President-Elect Trump’s state-court trial can be addressed in the ordinary course on appeal,” the majority explained in an unsigned order. “Second, the burden that sentencing will impose on the president-elect’s responsibilities is relatively insubstantial in light of the trial court’s stated intent to impose a sentence of ‘unconditional discharge’ after a brief virtual hearing.”

The president-elect responded in a somewhat muted fashion on his Truth Social account, saying that he “appreciate[d] the time and effort of the United States Supreme Court in trying to remedy the great injustice done to me.” Prior to the ruling, however, it was clear that even the mild punishment coming his way was too much for Trump to stomach; he wanted the entire case torn out root, branch, and stem.

He may yet get his wish. Four of the court’s members—Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh—signaled that they likely agree with Trump in Thursday’s order. There was once a time in American life when the notion of four justices taking this position on presidential immunity was well nigh unthinkable. If another justice ultimately joins that quartet in siding with Trump on appeal, it could expand “presidential immunity” well beyond what the justices have already given him.

The results of such a decision would be transformative, to put it mildly. First, Trump wants the justices to expand their original holding on “presidential immunity” to cover state crimes as well as federal ones. “President Trump noted that, upon his inauguration as the 47th President of the United States on January 20, 2025, he will be completely immune from all criminal process, state or federal,” Trump’s lawyers claimed in their stay application.

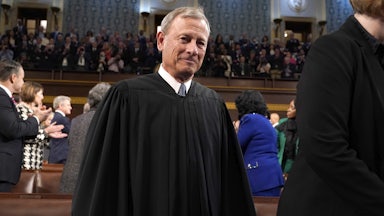

This is a bold assertion that is not supported by Supreme Court precedent. Trump v. United States, as its name implied, was about a federal prosecution of a former president. The Supreme Court did not consider whether presidents can be charged with state crimes after leaving office. Indeed, at the time, Chief Justice John Roberts’s reasoning largely revolved around separation of powers concerns. It goes without saying that separation of powers concerns do not extend to state courts or prosecutors. (They also didn’t really apply in Trump’s case since he was being prosecuted by the executive branch, but that battle was already lost last year.)

“Congress cannot act on, and courts cannot examine, the president’s actions on subjects within his ‘conclusive and preclusive’ constitutional authority,” Roberts wrote. “It follows that an Act of Congress—either a specific one targeted at the President or a generally applicable one—may not criminalize the president’s actions within his exclusive constitutional power. Neither may the courts adjudicate a criminal prosecution that examines such Presidential actions. We thus conclude that the president is absolutely immune from criminal prosecution for conduct within his exclusive sphere of constitutional authority.”

No state had ever attempted to prosecute a former president before Trump. There may be federalism grounds to bar some potential prosecutions; the Supreme Court has previously held that state governments generally cannot prosecute federal officials for acts performed in the course of their official duties. New York could not make it a criminal offense to enforce a specific federal law within the state’s borders, for example.

At the same time, granting blanket immunity from all state-level prosecutions to presidents could have dire implications. While federal offenses are also serious, the acts traditionally prosecuted by the states are central to what Americans consider to be criminal offenses: murder, manslaughter, rape, kidnapping, arson, burglary, fraud, shooting someone on Fifth Avenue, and so on. It is unthinkable that the justices could give anyone carte blanche to commit those crimes.

Trump also wants “presidential immunity” to extend beyond a president’s tenure in office. In his stay application, he asserted that just as sitting presidents can’t be targeted by state or federal prosecutions, neither can presidents-elect. “President Trump also stated that the doctrine of sitting-president immunity shields him from criminal process during the brief but crucial period of presidential transition, while he engages in the extraordinarily demanding task of preparing to assume the executive power of the United States,” Trump’s lawyers wrote, referring to lower-court filings.

The lower court disagreed, holding to the principle that there is only one president at a time. Trump is asking the courts to instead recognize that he is effectively a quasi-president right now and thus deserves special consideration. “These demands of time, energy, and attention are just as unconstitutionally burdensome and disruptive during the presidential transition as during the presidency itself,” his lawyers argued. “They are particularly burdensome when a president-elect faces the prospect of criminal judgment and sentencing during his transitional period.” Among those burdens is planning to annex Canada and Greenland.

Recognizing that presidential immunity applies outside a president’s term of office would rewrite the nature of the presidency itself. Trump has previously asserted, for example, that he can invoke the Presidential Records Act even when the sitting president is the one with the statutory discretion to lawfully waive or apply its terms. Taken together, he suggests that the presidency imbues its holders with some sort of special lifetime constitutional status and grants them unique legal powers and privileges beyond their actual term. This monarchical vision of the office is irreconcilable with the citizen-presidency created by the Framers.

Finally, Trump wants the Supreme Court to expand its definition of “official acts” to cover an extremely broad range of actions. What counts as an “official act” is pivotal under Trump v. United States because it affects what kind of evidence can be admitted in court. It is worth noting from the outset that the New York hush-money case focused on actions that took place before Trump became president in 2017, and he was not prosecuted for them until after his term ended in 2021.

One of the more controversial portions of the immunity case was about evidence relating to a president’s official acts. Roberts held that the ordinary rules of evidence for every other federal criminal defendant in the republic would be insufficient for cases involving ex-presidents. He warned that “use of evidence about such conduct, even when an indictment alleges only unofficial conduct, would thereby heighten the prospect that the president’s official decisionmaking will be distorted.”

This drew rebukes from not only the three dissenting liberal justices but also Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who rejected it in her concurring opinion. “On this score, I agree with the dissent,” she wrote. “The Constitution does not require blinding juries to the circumstances surrounding conduct for which Presidents can be held liable.” She instead argued that judges were well equipped to handle such concerns on a case-by-case basis under the ordinary rules of evidence. The other five conservative justices disagreed.

Trump had hoped to cover some of the evidence used in the case with presidential immunity so it can be thrown out. Among that evidence is a series of Twitter posts that Trump wrote in 2018 while president about his former legal fixer Michael Cohen after Cohen pleaded guilty to charges related to the hush-money payments. Trump argued that these posts were official presidential communications and that the courts could not use them as evidence against him.

“These public communications through President Trump’s social-media account—through which he routinely communicated with the public on matters of public concern during his presidency—were official actions of the President that could not be used against him during trial,” Trump’s lawyers argued. In other words, it was essential for the American people to read these Twitter posts in 2018, but would be unconstitutional for a New York jury to read them in 2024.

Trump also challenged other evidence as official acts, including testimony by White House aides about how they responded to the hush-money story and about whether Cohen could or would be pardoned—implicitly, prosecutors alleged, in exchange for not cooperating with law enforcement. But it is his assertion that even his statements to the American people can’t be used as evidence against him in court that is particularly alarming. If an ex-president’s own public statements can’t be used against him as evidence solely because he happened to be president at the time, then this new concept of presidential immunity is even more extreme and Orwellian than it first appeared to be last summer.

After Trump is sentenced on Friday, he will likely begin the appeals process to challenge his conviction as soon as he can. The Supreme Court’s order suggests that it is virtually guaranteed that the justices will eventually hear the matter—it takes only four votes to accept a case for review, and four justices have already signaled that they opposed the outcome here. Whether Chief Justice John Roberts and/or Justice Amy Coney Barrett ultimately give Trump what he wants on that appeal will shed light on how the court will treat a second Trump presidency—and the future of the office itself.