Though not particularly common in most herb gardens these days, rue can add a bit of bitter and bring balance to a dish gone too sweet or salty. Pennyroyal looks like mint and has a similar, zingy taste. Mugwort is tart. Tansy flowers into perfect yellow buds. Parsley is likely in your refrigerator right now, wilting a bit in your crisper drawer.

These herbs—along with a host of other foods, drinks, and cooking utensils—have all been used as abortifacients, or substances that terminate pregnancies, and have played a role in virtually every region of the world. Their usage has varied depending on the culture, political climate, concepts of gender, influence of faith, or power of the state. In many cases, they were used on this land before the formation of the United States, and they’ve been part of U.S. history since the early colonies.

But these herbal or food- and beverage-based abortifacients aren’t relics of the past. There are plenty of indications that the use of food to terminate pregnancies has been on the rise since the Dobbs verdict in 2022, which overturned Roe v. Wade and eliminated the federal right to abortion. And that trend—one that mixes folk knowledge with the modern era’s penchant for misinformation—comes with health risks and new, alarming, and distinctly American opportunities for surveillance and criminalization.

Farah Diaz-Tello, senior counsel at If/When/How, says criminalizing someone’s pregnancy loss because of their food intake “seems completely outlandish” because it would be impossible for a prosecutor to prove a causal link between eating abortifacient foods and terminating a pregnancy. But outlandish or not, she says, “it’s happening,” and an If/When/How report attests to the rising cases of prosecuting herbal or botanical abortions. (Even before Dobbs, it was happening: In 2011, a Manhattan woman was arrested for terminating her pregnancy with hierba de ruda, a commonly known herbal remedy available at botanicas.)

Often—but not always—the province of women, edible abortifacients have at turns been considered witchcraft, sacred, or quotidian. Before colonists arrived, Indigenous Americans used a host of herbal remedies for birth control and pregnancy termination, and different cultural groups within the United States today might call their remedies by different names. Through centuries of changing attitudes and legality around abortion, women continue to reach for these edible treatments when access to care becomes unavailable. Like coat hangers or knitting needles, these edible options are often sought in desperation—and they come with a cost.

In the colonies that predated the nation, colonists typically followed the laws of their home countries, according to scholarship on abortion in early America. But whether or not the European countries had specific abortion laws on the books, enforcement was nearly impossible—legal authorities could hardly establish pregnancy or whether termination was intentional. Pregnancy was typically understood to begin at the “quickening”—when the pregnant woman could feel her fetus moving. Surgical abortions were uncommon and dangerous—and most abortions relied on herbal abortifacients.

The enslaved population faced an entirely different set of circumstances and punishments: “Any uncovered attempt to choose to abort incurred the owner’s wrath, for it decreased his profits,” writes Zoila Acevedo in Women & Health. Still, histories from enslaved people refer to woodsy root concoctions and brews used to induce abortion—herbal remedies that could be assembled in secret.

Socially, abortion was somewhat out of style. “The tenor of the pre-revolutionary period was to encourage women, slave and colonist alike, to populate,” Acevedo writes. But most colonists were relatively free to terminate pregnancies, sometimes using herbs augmented with curious foods. The Archives of Maryland include a woman who claimed “she had twice taken Savin [oil derived from juniper berries]; once boyled in milk and the other time strayned through a cloath.”

Abortifacient herbs were widely known in the pre-revolutionary era through midwifery handbooks and guides, writes John M. Riddle in Eve’s Herbs. Riddle cites a 1681 trial record where one woman stood accused of brewing together an abortifacient blend of pennyroyal, horehound, nip, and marigolds for local women. In 1748, Benjamin Franklin even published a book with a detailed herbal abortion recipe.

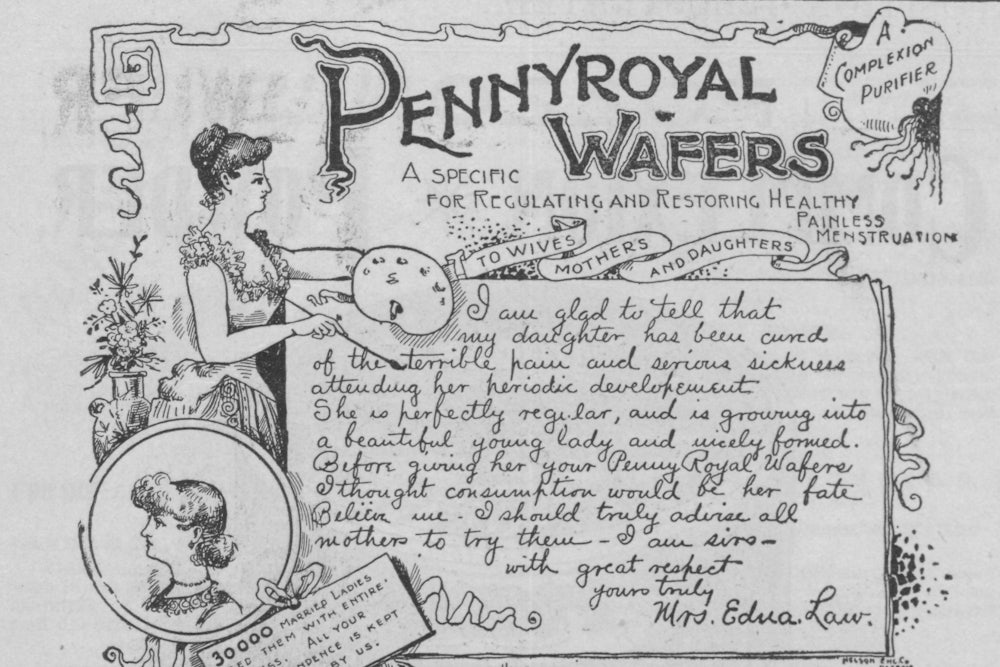

The nineteenth century was marked by social change, when American society embraced the Victorian sensibility. The country was hurtling toward a new conservatism around abortion, but herbal abortions continued. These herbal remedies were not simply relegated to folk medicine. In the late nineteenth century, pharmacists—or druggists, as they were called—sold tansy and pennyroyal pills among other abortion implements.

It wasn’t until 1821 that official legislation began restricting the purchase of abortifacients for free people in the United States. But it was the beginning of a transformative new paradigm: In 1857, the American Medical Association began to advocate curtailing abortion—and especially the power of female abortionists—by bringing pregnancy into the realm of the medical establishment, and, critically, decried the use of quickening as a turning point in the understanding of fetal life. Physicians leapt at the opportunity to curtail herbal use for both enslaved women and free women.

Through the Civil War, women were encouraged to replace the human death toll of the fighting, and the U.S. began enacting anti-abortion laws on a broader scale. By 1910, abortion was illegal in every state with exceptions for saving the mother’s life—except for Kentucky, where abortion was outright illegal. This sparked the beginnings of an underground abortion industry, one that would last through Reconstruction and, in various forms, until today.

Most herbs or other foods with abortifacient properties have other culinary and medicinal purposes. Tansy, for example, came to America in the 1600s not only in herb-flavored puddings and cakes but also wrapped in the trunks of European colonists who used the herb to treat constipation, intestinal worms, rheumatism, and even hysteria. (Its insect-repelling properties also made it a prime choice to protect meat from flies and ants.) Parsley shows up in early American cooking as an ingredient in marinades and other flavoring agents, as well as in cures for maladies including broken bones, madness, epilepsy, sore breasts, boils, and more.

From the Colonial period, ginger root and ground ginger were highly popular seasonings, widely available and “used to season stuffings, puddings, sweets, breads, cakes and pies,” according to a 1983 New York Times piece. And mugwort—with its fragrant, bitter leaves that can be eaten raw or cooked—can be used medicinally to treat digestive problems, irregular menstruation, and high blood pressure, among other issues, and is used in cooking around the world.

But these foods and herbs made for abortifacients because they could also be poisonous—both to a fetus and a mother. The classic roster of herbs like pennyroyal, parsley, blue cohosh, and mugwort are all toxic when taken in high enough quantities or in certain forms. A single tablespoon of concentrated pennyroyal oil, for example, can lead to fainting, seizures, cardiac arrest, coma, liver injury, and multiple organ failure. Study after study sounds the alarm on blue cohosh, including a case where a pregnant woman tried to induce abortion with a tincture of blue cohosh and developed nicotinic toxicity. Consuming large amounts of parsley—certainly the amount needed for an abortion, which can happen via tea or vaginal suppository—can lead to anemia and liver or kidney problems.

But some of the associations that have come to be made between foods and abortifacients are purely false—and seem much more indicative of the era’s particular interests and mores than of any proven efficacy. In the 1950s and ’60s, the Coca-Cola douche emerged, a folk remedy that served as either an abortifacient or a spermicide, depending on who you ask. (Reports vary, but people either believed the chemicals or the bubbles in the beverage could kill sperm or terminate a pregnancy.) In a 1985 article debunking the efficacy of Coke douches, Dr. Gerald Bernstein told the Los Angeles Times that he remembers the Coca-Cola douche existing within teenage life in the ’60s, when birth control wasn’t widely available. “It was the thing you did on the beach,” he told the Times. The classic, curving Coke bottle made for an easy application referred to as the “shake and shoot.”

Coke as contraception, of course, is a myth: Scientists have confirmed that it has little to no ability to stop or terminate a pregnancy. Decades later, though, posts seeking information on Coke abortions abound on sites like Quora. Because when abortion care isn’t available, people hoping to regain bodily autonomy will reach for anything—and only sometimes does the solution deliver.

I likely first encountered the 2002 zine Herbal Abortion: a woman’s d.i.y. Guide on Livejournal a few years after its publication. I was a teenager just beginning to turn over the notion that I didn’t ever want to be pregnant, and I must have been curious. In it, the author, known only by the pseudonym Annwen, compiles what they call “age-old knowledge that has been systematically suppressed by those—from medieval witch-burners and clergy to modern day doctors and politicians—who would usurp the power of a woman’s control over her own body.” The zine then lays out in striking detail instructions for herbal abortions and advocates for a somewhat radical self-determination: These herbs could kill you, but it’s up to you.

“Just because herbal abortion uses herbs does not mean it will be gentle or easy,” Annwen writes, providing specific instructions for herbal use as tea, tinctures, or capsules. “There are certainly risks with any medical treatment. Natural does not equal safe.” They are highly nitpicky to use, they stress, and mistakes can be costly.

Annwen is right to offer caution: In tests of herbal abortifacients’ efficacy, most herbs require such a high quantity, administered with such specificity, that they are “virtually always toxic to the pregnant person,” Dr. Aviva Romm, a women’s health physician, midwife, and herbalist who wrote the textbook Botanical Medicine for Women’s Health, told The New York Times. “My hard-line position, for 35 years, has been that they are not reliably effective,” Romm said.

Risks around alternative, underground abortions stretch back historically. Leslie J. Reagan’s seminal 1996 book, When Abortion Was a Crime, tracks the death toll and dangerous effects of illegal abortions without adequate medical care. The two decades before the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling saw an estimated 200,000 to 1.2 million illegal abortions per year, with stark mortality rates. In 1965, illegal abortion accounted for 17 percent of all maternal deaths that year, and that number only reflects official reports—the actual number is much higher.

Those stark mortality rates disproportionately affected women of color and poor women. Reagan points to a 1917 study showing that Black women were more likely to self-induce as a matter of access, whereas white women were more likely to visit a midwife or physician; self-induction meant higher levels of medical complications.

It was during this era that abortion—like childbirth—moved squarely into the hospital setting. In the 1940s, the American medical establishment undertook an effort to sterilize women who came in with illegal abortion complications. Refusing the sterilization, some women “took abortion into their own hands,” Reagan writes. That meant more self-induction in increasingly risky methods—famously, douching with soap and bleach was a frequently fatal option—as was the injection of lye. (Today, food-grade lye is used to cure all manner of food, including olives and pretzels.)

But “desperate and low-income women used many of the methods used by previous generations,” Reagan writes. They turned to what was available, and while homes had the infamous, gruesome coat hanger, they also had pantries of food or drawers of cooking utensils. “One woman described taking ergotrate, then castor oil, then squatting in scalding hot water, then drinking Everclear alcohol.”

By the early 1960s, 44 states limited abortion access to instances where the life of the mother was threatened, and only Pennsylvania allowed all abortions. The effect meant that fewer and fewer doctors performed the various procedures, driving women again to underground methodology, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

In that pre-Roe era, one doctor remembers “some of the sickest people I have ever seen in my life”—others relate gruesome images and stories of sheer desperation. Among other kitchen items, women used cut-glass salt shakers and chicken bones. In 1971, a Los Angeles teacher, abortion educator, and mother of four named Lorraine Rothman devised a “menstruation extraction device,” which used a canning jar.

In 1973, the Roe v. Wade decision enshrined the right to abortion throughout the country. But Roe didn’t end abortions outside of the legal, medical framework the ruling established. Four years later, the Hyde Amendment banned using federal funds to support abortion services, which increased the costs of and dramatically limited access to abortion, especially for more vulnerable populations, like Black and Hispanic women. With that change came a renewed interest in herbal abortions.

While abortion was theoretically legal, broad access wasn’t guaranteed. And as ever, people seeking abortions turned to shared, community knowledge. In 1989, a video of Rothman’s canning jar device began to circulate in women’s groups around the country as another court case threatened abortion access. The reaction and panic about the video, titled “No Going Back,” demonstrates the attitudes toward at-home, outside-the-medical-establishment abortions, including by pro-abortion groups. The National Abortion Federation found the video “both medically dangerous and politically misguided.” The National Organization for Women saw internal divisions about the merit of underground action. For Rothman, who received a patent for her device, self-management remained a necessity for survival—and it would continue with or without state support.

“What we’re saying is, if we don’t get cooperation from our society to help us, we are forced to take matters into our own hands, because women will continue to get pregnant when they don’t want to in our society,” she told The Washington Post in 1989. “And we have no other choice but to protect ourselves.”

It’s a sentiment that extends to the present: A look at four studies between 2010 and 2020 found that “between 2 percent and 13 percent of people accessing facility-based care reported having taken or done something to end a pregnancy on their own without medical assistance.” And a 2021 study surveyed 14 people who had self-managed abortions—some reported herbs like parsley, dong quai, rose hips, ginger root, chamomile, and black cohosh. One drank vodka for four hours. Most of the study’s participants had found their information online and considered availability, safety, and legal repercussions.

When the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision struck down Roe v. Wade on June 24, 2022, it created what a Human Rights Watch paper called “an unprecedented human rights crisis.” Unsurprisingly, Dobbs disproportionately impacts marginalized populations, including Black, Indigenous, and people of color; people with disabilities; immigrants; and those living in poverty, who are most likely to lose access to care and to be surveilled—and criminalized. Dobbs also spawned an entirely novel set of criminalizations. Providers and patients are now at more risk than ever for prosecution or civil suit; Dobbs ushered in a new era of reproductive surveillance where our purchases, searches, and consumption habits might land any one of us facing legal recrimination.

Since Dobbs, the interest in alternative methods has skyrocketed. Google trends reports a massive spike in searches for “herbal abortion” in the weeks following the ruling, and the 2002 herbal abortion handbook also shot up in searches. (The week of President Trump’s second electoral victory also saw a bump.) Herbal abortion became a TikTok trend in the month after the Dobbs ruling, and misinformation about how to safely self-manage abortion spread rapidly. Online forums touted papaya as an abortifacient—which has been historically used outside of the U.S. for various medicinal purposes with conflicting accounts of efficacy—and the posts are either summarily debunked by responders or encouraged.

It’s a perfect storm of the current American social and political scene: rampant, dangerous misinformation growing by the day; a decreasing trust in medical institutions; and the ongoing curtailing of safe access to abortion. And amid this renewed interest, the increased criminalization of pregnant people’s behavior is alarming.

“Once a prosecutor has decided they want to criminalize someone for their pregnancy outcome—often because of their race, economic status, drug usage, or engagement in sex work—they will really stop at nothing to build a case,” says Diaz-Tell of If/When/How. “I’ve seen prosecutors pursue wild theories like using cinnamon supplements—which are not a known abortifacient at all—or say that someone not taking prenatal vitamins during their pregnancy is evidence that their stillbirth was, instead, a murder.”

A lack of scientific evidence isn’t stopping criminalization, Diaz-Tell says. And there already exists an entire surveillance infrastructure to support these criminalization efforts—the food-tracking apps that millions of Americans use to lose weight or otherwise monitor their nutrition. Any pregnant person with a diet or nutrition app might track their daily caloric intake: a papaya with breakfast or their daily chamomile tea. Those meals become data—data that belongs to the corporation and not the consumer.

Emily Tucker, executive director of the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown Law, analyzed the privacy policies for three popular food-tracking apps: MyFitnessPal, Weight Watchers, and Lose It!

“None of them are really privacy policies. They’re all statements that are designed to alert the user that they don’t have any privacy at all,” she says. “I saw almost nothing in those policies that reflected any kind of restriction or restraint that the company was going to impose on itself.” In Tucker’s reading of those policies, these corporations reserve the right to hand over user data to law enforcement at their own discretion.

“Maybe it’s just sort of up to the whim or the discretion of whoever the person in charge happens to be at that moment,” she says. “With these smaller companies, I only have anecdotal experience, but my suspicion is that it’s probably very ad hoc.” (I reached out to Weight Watchers, MyFitnessPal, and Lose It! to inquire about their policies and did not receive a response.) It’s a remarkable vulnerability and a chilling reality in an ever-hungrier surveillance state.

It is perhaps distinctly American to see food consumption as a pathway toward criminalization. Food is entirely politicized in America—SNAP benefits only apply to certain foods imbued with moral goodness, what one chooses to eat signals one’s political alignments and virtues, and health guidelines are created in partnership with food lobbies. Surveillance by corporations to enforce state ends is inherent in the alliance between private and public interests. And a steady feed of misinformation at the fingertips of the most desperate and abandoned by the state isn’t all that different from the snake oil salesmen of the American past. Each is as American as any picnic spread: potato salad laced with parsley, a mason jar for preserves, or a glass bottle of Coke.