Last year, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority ruled that the president of the United States had “absolute” criminal immunity for his “official acts,” as well as lesser degrees of immunity for other acts committed while president. This decision in Trump v. United States came under widespread and withering criticism from the dissenting justices and ordinary Americans alike.

“The relationship between the president and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned in her dissenting opinion. “In every use of official power, the president is now a king above the law.”

Only a handful of people—other than Trump himself and his lawyers, of course—celebrated the ruling in full on its merits. Among them was Kevin Roberts, the president of the far-right Heritage Foundation and the overseer of Project 2025, the manifesto that essentially became the second Trump administration’s governing blueprint. He argued that the court’s ruling had not defied American political thought but rather echoed it.

“The Supreme Court ruling yesterday on immunity is vital, and it’s vital for a lot of reasons,” Roberts claimed. “But I would go to Federalist No. 70. If people in the audience are looking for something to read over Independence Day weekend, in addition to rereading the Declaration of Independence, read Hamilton’s No. 70 because there, along with some other essays, he talks about the importance of an energetic executive.”

Federalist Number 70 is one of 85 essays written by three of the Framers—Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay—to defend and promote the new Constitution during the ratification debates in 1788. Almost 250 years later, it may be the most important one in terms of today’s political landscape—in large part because its proponents have used and misused it to do so much damage to our constitutional order.

No. 70, which was written by Hamilton and focuses on the nature of the presidency, is perhaps the central text for those who advocate for the “unitary executive” theory. Their choice is somewhat understandable: Hamilton argues forcefully for creating a presidency with one officeholder instead of a “plural executive,” as could have been found in some states and foreign republics at the time.

This basic fact about our constitutional structure—that we have one American president instead of two Roman consuls, five Napoleonic directors, or so on—is unquestioned today. Nobody is arguing for a second or third president. (One is quite enough at the moment.) Unitary executive theory proponents, however, take a skewed view of the text, instead using it to exalt the executive branch as the one true representative of the people’s will, while downplaying legislative authority and legitimacy.

The Supreme Court’s invocation of No. 70 has been increasingly frequent—and increasingly disastrous. In addition to the immunity ruling, the conservative justices have invoked it to justify broad interpretations of executive power and authority. Perhaps the most common adjective drawn from No. 70 is that the Constitution created an “energetic” executive branch that would be capable of vigorously enforcing the nation’s laws. This understanding is one with which Hamilton would likely agree, since he described “energy in the executive” as “a leading character in the definition of good government.”

“It is essential to the protection of the community against foreign attacks,” Hamilton continued; “it is not less essential to the steady administration of the laws; to the protection of property against those irregular and high-handed combinations which sometimes interrupt the ordinary course of justice; to the security of liberty against the enterprises and assaults of ambition, of faction, and of anarchy.”

This was not an abstract problem for Hamilton and his contemporaries. The Framers gathered at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia to address the defects of the Articles of Confederation, the nation’s first postrevolutionary form of government. Foremost among its many defects were the lack of an executive branch to enforce the Congress of the Confederation’s laws and a federal judiciary to interpret them.

Civil unrest, most notably Shays’s Rebellion in 1786, was the “anarchy” that led Hamilton and other Framers to propose an executive branch that could readily respond to crises and enforce the laws. “A feeble Executive implies a feeble execution of the government,” he wrote. “A feeble execution is but another phrase for a bad execution; and a government ill executed, whatever it may be in theory, must be, in practice, a bad government.”

Hamilton described an “energetic” executive as one that possessed four traits: unity, duration, an “adequate provision for its support,” and “competent powers.” At the same time, he was equally sensitive to fears that a president could be a dictator or a threat to liberty. He explained that “safety in the republican sense” would come from a “due dependence on the people” and a “due responsibility.”

The American presidency, he explained, met these conditions. There would be one president instead of multiple executives. He would serve a four-year term, more than the three years served by the governors of New York, where the Federalist Papers were first published, but far less than the life tenure of a British king. (Hamilton also explained how republican liberty could be secured, but we’ll return to that a little later.)

Unitary executive theorists love to invoke the “energetic” portion to explain why the president should not be encumbered with restraints from Congress or the judiciary. John Yoo, a conservative legal scholar who served in the George W. Bush administration, wrote a 2001 memo arguing for broad presidential war powers after the 9/11 attacks that rejected Congress’s exclusive power to authorize military operations.

“‘Decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch will generally characterize the proceedings of one man in a much more eminent degree than the proceedings of any greater number,’” he wrote, quoting from No. 70. “The centralization of authority in the president alone is particularly crucial in matters of national defense, war, and foreign policy choices, where a unitary executive can evaluate threats, consider policy choices, and mobilize national resources with a speed and energy that is far superior to any other branch.”

It is worth emphasizing here that No. 70 is not really about the separation of powers, except insofar as it discusses the executive branch’s powers in great detail. Yoo’s quotation of “proceedings of any greater number” might read as if it were referring to Congress, given the context of Yoo’s memo. In reality, Hamilton didn’t have the legislative branch in mind at all. Rather, he was responding to Anti-Federalist concerns about the presidency and public suggestions that a plural executive would work better.

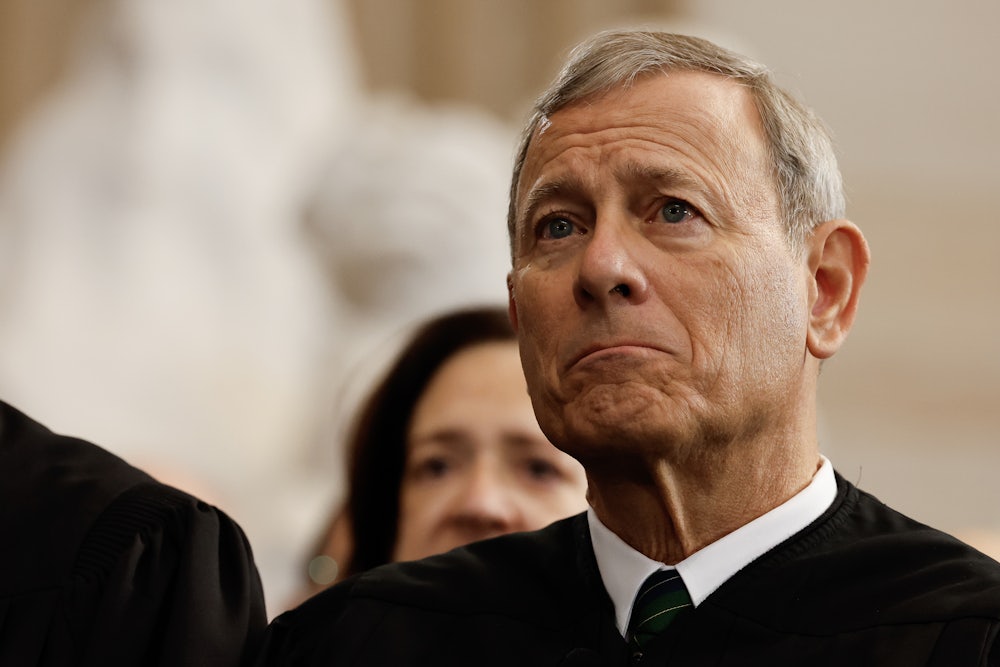

This feat of textual sleight of hand is one thing when done in a White House memo. It is something else entirely when the misapprehended text is subsequently applied by the Supreme Court. In 2020, the Supreme Court struck down the for-cause removal protections that Congress had established for the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in Seila Law v. CFPB. Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, expounded at length upon how the Constitution divided power.

“In addition to being a historical anomaly, the CFPB’s single-director configuration is incompatible with our constitutional structure,” Roberts wrote for the court. “Aside from the sole exception of the presidency, that structure scrupulously avoids concentrating power in the hands of any single individual.” This was relevant because when the court had previously upheld removal protections, they had only applied to multimember boards like the Federal Trade Commission. Here, Hamilton’s concerns about a plural executive are reasonably relevant.

Along the way, however, Chief Justice Roberts laid out what might be his most comprehensive explanation for how he sees the Constitution’s separation of powers. First, he noted that the Framers had divided power in the legislative branch by creating a House of Representatives and a Senate. Then he noted that the executive branch was “a stark departure from all this division,” suggesting that it held some special role in the constitutional order. This special role came at Congress’s expense.

“The Framers viewed the legislative power as a special threat to individual liberty, so they divided that power to ensure that ‘differences of opinion’ and the ‘jarrings of parties’ would ‘promote deliberation and circumspection’ and ‘check excesses in the majority,’” he wrote, quoting at length from No. 70. “By contrast, the Framers thought it necessary to secure the authority of the Executive so that he could carry out his unique responsibilities.”

It may surprise you to discover that this isn’t what Hamilton really meant in Federalist No. 70. Hamilton indeed wrote all the quoted portions in the above excerpt, but he was plainly not describing the “legislative power” as a “special threat to individual liberty.” That anti-parliamentary gloss comes entirely from Chief Justice Roberts.

In No. 70, when discussing the merits of a plural executive versus a single executive, Hamilton discussed human nature at length. “Wherever two or more persons are engaged in a common enterprise or pursuit, there is always danger of difference of opinion,” he wrote. If two or more people hold a public office, there is the risk of “animosity” and “bitter dissensions.”

If these tendencies afflict and divide a nation’s plural executive, Hamilton warned, “they might impede or frustrate the most important measures of the government, in the most critical emergencies of the state.” Worse still, he claimed, such divisions could “split the community into the most violent and irreconcilable factions, adhering differently to the different individuals who composed the magistracy” and lead to civil war.

Upon the principles of a free government, Hamilton continued, these divisions “must necessarily be submitted to in the formation of the legislature,” but he opined that it would be “unnecessary, and therefore unwise, to introduce them into the constitution of the executive.”

This is where his discussion turns to what Chief Justice Roberts (mis)quoted. “It is here too that [divisions] may be most pernicious,” Hamilton wrote. “In the legislature, promptitude of decision is oftener an evil than a benefit. The differences of opinion, and the jarrings of parties in that department of the government, though they may sometimes obstruct salutary plans, yet often promote deliberation and circumspection, and serve to check excesses in the majority.”

In no way does Hamilton use these observations of human nature to claim that the legislative branch is a “special threat to individual liberty,” as Roberts suggests. What may be unavoidable and perhaps sometimes even beneficial for a legislature, Hamilton warned, would only be disastrous for the executive. “No favorable circumstances palliate or atone for the disadvantages of dissension in the executive department,” he wrote, warning that they “constantly counteract” the “vigor and expedition” that he saw necessary to a functional executive branch.

In his Seila Law opinion, Chief Justice Roberts went on to cite No. 70 in piecemeal fashion to explain how the Framers structured the executive branch. “They chose not to bog the Executive down with the ‘habitual feebleness and dilatoriness’ that comes with a ‘diversity of views and opinions,’” Roberts wrote. “Instead, they gave the Executive the ‘decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch’ that ‘characterise the proceedings of one man.’

“To justify and check that authority—unique in our constitutional structure—the Framers made the president the most democratic and politically accountable official in government,” Roberts claimed. “Only the president (along with the vice president) is elected by the entire nation. And the president’s political accountability is enhanced by the solitary nature of the executive branch, which provides ‘a single object for the jealousy and watchfulness of the people.’”

Roberts is only partially correct here. The president’s political accountability for the executive branch is indisputable, as best summarized by Harry Truman’s “the buck stops here” mantra. But the presidency’s democratic nature is a more recent and debatable trend. Almost half of the states that elected George Washington to his first term in 1788 did so through legislative appointment. Americans then and now vote for presidential electors to cast ballots in the Electoral College, which sometimes chooses the second-place candidate to lead the nation.

Congress, on the other hand, is entirely elected by Americans—the House since 1792 and the Senate since 1914. So crucial is its elective and national nature that Article 1 goes into great detail about when and how the House’s members would be elected. As I’ve noted before, Congress’s actual powers speak clearly about the paramount role that it would play once the Constitution was ratified.

The Roberts court’s habitual disdain for Congress and its reflexive tendency toward hyperpresidentialism led to its decision in Trump v. United States. There it declared, for the first and only time in two and a half centuries, that the president was above the law. Short of rejecting democratic governance altogether, it is hard to imagine a greater heresy against the American constitutional order.

There is, obviously, no “presidential immunity clause” in the Constitution. The conservative justices’ un-originalist efforts to imagine one into it cannot be supported by text or history. Invoking No. 70 was a key portion of Roberts’s case for its functional necessity. The executive branch would be severely weakened, the chief justice wrote, if presidents could face prosecution after leaving office.

“[The Framers] deemed an energetic executive essential to ‘the protection of the community against foreign attacks,’ ‘the steady administration of the laws,’ ‘the protection of property,’ and ‘the security of liberty,’” Roberts wrote in the immunity ruling. “The purpose of a ‘vigorous’ and ‘energetic’ Executive, they thought, was to ensure ‘good government,’ for a ‘feeble executive implies a feeble execution of the government.’”

Federalist No. 70 is also not the only place where the Framers discussed the presidency. In Federalist No. 69, for example, Hamilton sought to rebut both critics and concerned citizens who feared that the Constitution would create a kingly dictator. To distinguish the two, he pointed first to ways in which they can be held accountable.

Hamilton noted that the king of Great Britain is “sacred and inviolable” under the law and that there is “no punishment to which he can be subjected without involving the crisis of a national revolution.” This was likely meant as a reference to the fate of Charles I, who lost the English Civil War in the 1640s and was subsequently tried and executed by Parliament.

American presidents, Hamilton explained, could be deposed without such extraordinary measures. The president “would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.” Sotomayor pointed specifically to this passage in her dissent from the immunity ruling.

Roberts, in his majority opinion, brushed off this evidence—and other indications that the president did not possess some special form of legal immunity—without engaging with it. “Some of [the Sotomayor dissent’s] cherry-picked sources do not even discuss the president in particular,” he claimed, referring to citations of the Constitutional Convention’s debates. On Federalist No. 69 in particular, the chief justice claimed that it did not “indicate whether [the president] may be prosecuted for his official conduct.”

It is worth dwelling on Roberts’s interpretation a little further because it illustrates the magnitude of his—and the court’s—error. Here we have a direct statement from Hamilton that says the president can be held “liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.” This is no mere stray thought or idle observation; he explicitly mentions it in the context of the British king’s own sovereign immunity.

Roberts says this statement carries no weight because it sheds no light on whether the president can be prosecuted for his “official conduct.” This is plainly wrong. Hamilton argued against a plural executive in No. 70 in part because he believed that it would be more difficult to ascribe blame to officials—and thus subsequently hold them accountable—if they abused their powers.

Some historical republics had divided power among multiple high magistrates, most famously pre-imperial Rome. Hamilton disfavored this approach because it “tends to deprive the people of the two greatest securities they can have for the faithful exercise of any delegated power.” One of those securities was the “restraints of public opinion,” which “lose their efficacy” if blame is diffused between multiple people.

The other security was the “opportunity of discovering with facility and clearness the misconduct of the persons they trust, in order either to their removal from office or to their actual punishment in cases which admit of it.” In short, Roberts claimed that criminal immunity was necessary for the unitary executive to operate. Hamilton, however, made clear that one reason for having a single president was to make it easier to prosecute abuses of power—or, as Roberts would refer to them, “official acts.”

Federalist No. 70 will likely continue to be a key force in the Supreme Court’s rulings on behalf of the Trump administration in the years ahead. Its invocation in Seila Law means No. 70 will almost certainly be used by the court to justify overturning Humphrey’s Executor in the Federal Trade Commission dismissal case later this term, for example. Hamiltonian quotes might also be used to justify Trump’s deployment of the National Guard or other extraordinary uses of executive power.

Nonetheless, I can only echo the Heritage Foundation’s call to reread No. 70 whenever the Supreme Court cites it. Americans will be easily able to glean Hamilton’s actual intent: to explain how and why their new presidency could be held accountable to the popular will and constrained by the rule of law. No amount of “cherry-picking,” as the chief justice so aptly put it, can change that.