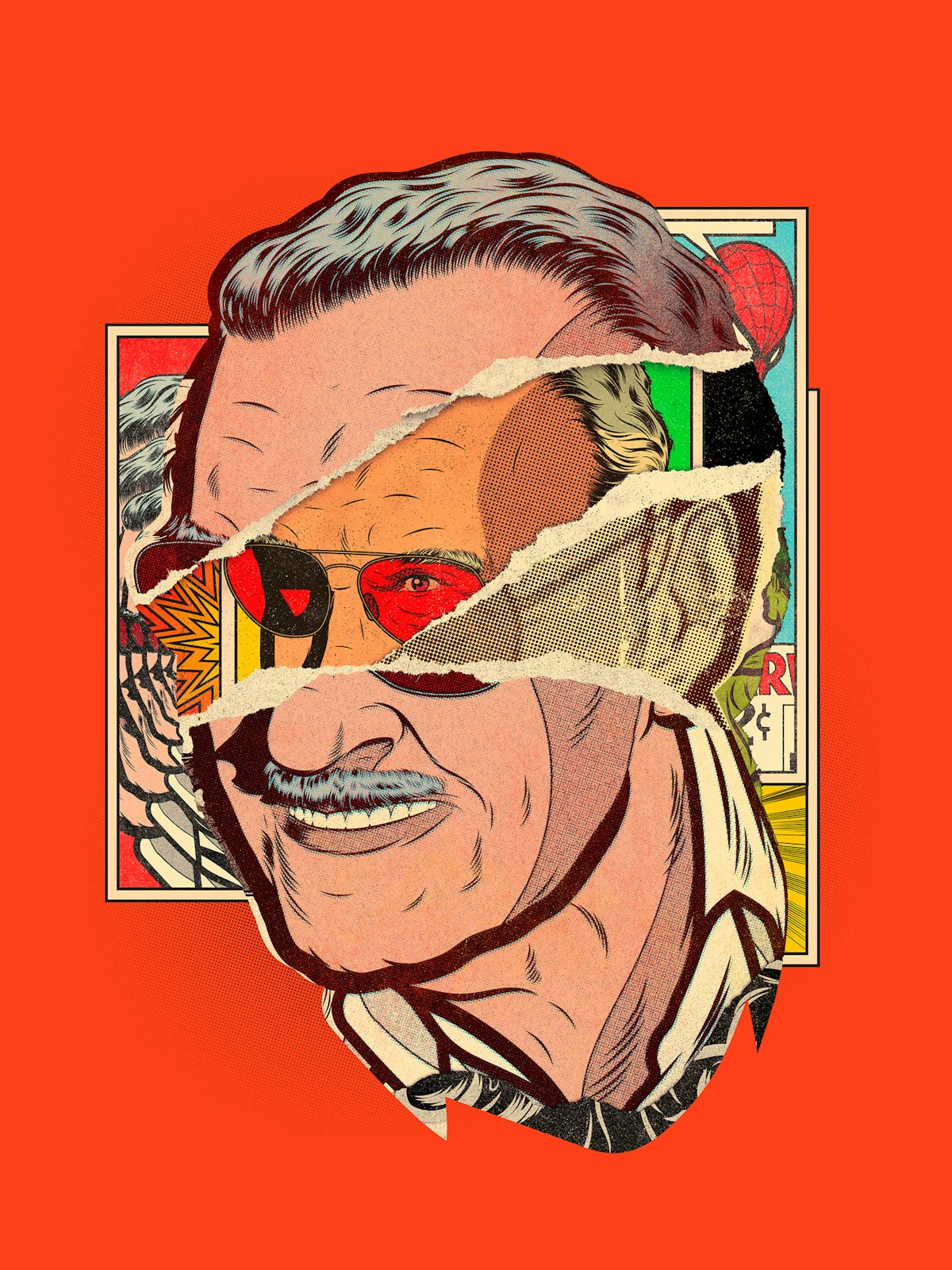

A nerdy slacker is hanging around the mall, having been dumped by his girlfriend earlier that day. He is staring in the window of a lingerie store, when a sharply dressed older guy with gray hair and tinted glasses approaches and strikes up a conversation. As he casually mentions “an issue of Spider-Man I did,” the younger man’s eyes slowly widen. He realizes that he is talking to Stan Lee, the originator of some of the best-known and most beloved characters in American pop culture, including Spider-Man, the Hulk, the X-Men, and Iron Man. “Shit, man,” he exclaims, “you are a god!”

This scene from the 1995 movie Mallrats captures the long-prevailing view of Lee, the man behind Marvel during the comics renaissance of the 1960s, when superheroes became wittier and more angsty, more human than ever before. To many fans, he was a kind of god. Yet the same month the movie was released, the magazine The Comics Journal devoted an issue to Lee that was not entirely favorable. The cover featured a caricature of him as a grinning ringmaster with an oversize head, and cover lines teased “a circus of celebration” alongside “a carnival of criticism.” Inside, one article discussed “The Two Faces of Stan Lee,” while another asked, “Once and for All, Who Was the Author of Marvel?” As Abraham Riesman notes in his new biography, True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, the answer in the piece was not the man who took all the credit.

Certainly, Lee helped build the Marvel empire through his work as a writer, editor, and publisher there. But by the mid-’90s, his status as a trailblazing genius was in dispute. The comics artist Jack Kirby, who had worked with Lee for decades, had been saying that he alone was the progenitor of most of the company’s novel and long-lasting heroes and villains. “Stan Lee and I never collaborated on anything!” Kirby said in a 1990 interview with The Comics Journal, going so far as to reject the narrative that he and Lee had invented characters like the Fantastic Four and Thor together. “I could never see Stan Lee as being creative,” he said. “I think Stan has a God complex. Right now, he’s the father of the Marvel Universe.”

Lee would live until 2018, and, superficially, he would remain the father of the Marvel Universe. Rejecting Kirby’s claims, he continued to serve as a figurehead even after he stopped working at the company, and a series of cameos in its increasingly successful superhero movies ensured his fame. With 23 titles to date, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become the highest-grossing film franchise of all time, its products almost impossible to avoid. Arguably, more than any other single company, Marvel has defined the modern idea of the superhero, through its tales of ordinary people who gain extraordinary powers and use them to save society.

Lee’s life was, however, far bumpier and more complex than the success story he cultivated. A major figure in a field he never liked, Lee became known for dreaming up characters that quite possibly were not his. His reputation flourished even as his ideas flopped. Some people found him delightful to work with, while others deeply resented him. He promoted the black-and-white morality of the superhero world, but his own relationships were a tangle of ethical uncertainties. As much as his flashes of brilliance, it was these weaknesses that left their mark on Marvel comics.

Stan Lee was the invention of a young and ambitious New Yorker named Stanley Lieber. His parents, Celia Solomon and Jack (formerly Iancu) Lieber, were Jewish immigrants from Romania who had met in New York City and married in 1920. Two years later, Stanley was born. Emotionally distant and strict, his father worked as a dress cutter but struggled to find jobs during the Great Depression. Celia was quiet but more doting, especially on Stan, who was smart but not especially interested in school. The dominant theme in Lee’s reminiscences of his childhood is the desire to escape. He wanted out of his circumstances—family drama, economic hardship, Jewishness. In his high school yearbook, he declares his goal: “Reach the Top—and STAY There.”

It was Lee’s family that helped him land his first job in comics, although he didn’t publicly admit it for years. Through an uncle’s connections, Lee was hired to assist Joe Simon, the first editor of what was then called Timely Comics. The Golden Age of comic books was already underway, and Jack Kirby was there, working with Simon. After a brief period in which Lee ran errands and did odd jobs, Simon gave him his first professional writing gig, drafting a two-page–text story for an issue of Captain America. The piece wasn’t particularly notable except for its byline: “Stan Lee.” “I somehow felt it would not be seemly to take my name, which was certain to one day win a Pulitzer, and sign it to mere, humble comic strips,” he later explained of the choice. He never won a Pulitzer, but he kept the pseudonym, eventually adopting it as his legal name.

Lee was still a novice when it came to comic books, but he rose quickly at the company. When a dispute led to the firing of Kirby and Simon, Lee—who was only 19—took over as editor. Minus a break to serve in the Army from 1942 to 1945, during which time he continued to write stories, he would remain employed by or contracted to Timely, which became Marvel, in some form for the rest of his life.

It was not an association he wanted. As the mid-century approached, Lee became an adult by conventional standards: He met and married his wife, Joan Clayton Boocock, in 1947, then moved from the city to a house on Long Island; three years later, the couple had a baby, Joan Celia Lee. Yet he was still working in an industry whose products were primarily pulpy entertainment aimed at kids. Returning to the familiar desire for escape, he looked into launching a textbook company, freelanced in broadcasting, and worked on getting several newspaper comic strips, which were more respected at the time, into print. He also attempted to position himself as a comic-book impresario, perhaps recognizing that he could, in Riesman’s words, “transcend that industry by positioning himself as an expert on it.” Nothing stuck. In an autobiography outline he wrote decades later, Lee called the 1950s his “Limbo Years.” “I still felt I was going nowhere,” he lamented. “How could I keep getting older and older and still be writing comic books? Where and when would it stop?”

Rather than stopping, he soon started on a series of books that made him famous and revolutionized the field. The superhero market had begun to pick up again—thanks to rival DC Comics—and in 1961, Marvel published Fantastic Four #1, which introduced a quartet that was hit with cosmic rays while out on a rocket ride. “Superhero stories were supposed to be about genial people who happily stumble upon superhuman abilities, then go on their merry way toward justice,” Riesman writes. “That mold was forever broken” with the Fantastic Four, who are depicted as having their powers “forced upon them quite painfully.”

The first issue was instantly popular, and Marvel followed it up with more superheroes, including the Hulk, the powerful brute that scientist Bruce Banner becomes when he’s stressed or angry; Thor, a riff on the hammer-carrying Norse god of thunder; and perhaps the most popular, Spider-Man, the alter ego of nerdy teenager Peter Parker, who gets bitten by a radioactive spider. What connected all these characters and made them novel were their imperfections. They weren’t generic, all-around superpeople who always did the right thing, but rather, Riesman writes, “flawed, vivid, and unique, their adventures idiosyncratic and imaginative.” As Lee once put it, “our superheroes are the kind of people that you or I would be if we had a superpower.”

By the 1960s, he had a bullpen of distinctive writers and artists, including his younger brother, Larry. Steve Ditko designed Spider-Man’s red-and-blue costume and, over the course of the series’ first 38 issues, shaped him as the physically acrobatic and emotionally anguished young man that we still know him as today. Kirby, who had recently returned to Marvel and drew many of the other characters, set a standard for second-wave superheroes with his work’s incredible dynamism, which manifested in powerful figures, propulsive action scenes, and unusual perspective. Lee contributed a style of dramatic narration that spoke straight to the reader (unheard of at the time) and clever dialogue that made the characters feel more human (Riesman cites Spider-Man’s quip to a foe, “I’ll bet you’d be great at a party!”). The team hooked readers by teasing future episodes or leaving tensions unresolved, and by having heroes appear in each other’s stories, as with the Avengers, who were a collection of preexisting characters. Unlike its competitors, “Marvel was a living, breathing, evolving universe,” Riesman observes. “It was a brilliant strategy for next-level storytelling, yes, but an even more brilliant marketing ploy.”

Part of Marvel’s success came from an unconventional way of working. Traditionally, a writer would come up with a script that placed both words and images on the page, then hand it off to the artist to fill in. By contrast, in what’s come to be known as the Marvel Method, the writer and artist began the process with a conversation about character and plot. The artist would then draw the story first, before passing it off to the writer to add dialogue and narration.

In this arrangement, the artist became more than just a person supplying imagery to fit a script; he was also a storyteller and writer with extensive creative freedom. “I realized that [drawing] comics from a script was absolutely paralyzing and limiting,” John Romita Sr., who served as Marvel’s art director in the 1970s and ’80s, tells Riesman. “When you had the option of deciding how many panels you’d use, where to show everything, how you pace each page out, it’s the best thing in the world. Comics becomes a visual medium!” This undoubtedly made Marvel’s line markedly different from earlier comics. But it also meant that there was no easily identifiable origin point for any particular idea—just a discussion that took place between two people who, as in the case of Kirby and Lee, could both claim to have invented the same characters independently.

Lee did make efforts to give his collaborators some of their due. Comics had no standards for citing creators, and he implemented one by placing itemized credits at the front of each issue. He listed by name the writer, penciler, inker, and letterer; he also often praised them in letters to fans and public interviews. Yet, as Marvel became more and more successful, the charismatic Lee became the focus of the attention. Glowing newspaper articles positioned him as the mastermind of the whole operation, when in reality artists like Ditko and Kirby were doing much of the plotting and scripting on their own, while getting paid solely as artists, not writers.

As the ’60s progressed, Lee expanded the Marvel brand via spin-off products that boosted the company’s profile and profits—as well as his own career. The writers and artists, who were often freelancers, didn’t receive any royalties for the use of their work. Larry tells Riesman that as he watched his older brother get rich and famous, he was struggling to pay rent. Fed up, Ditko left the company in 1965. Kirby did the same five years later. Meanwhile, Lee’s ascent continued, and in 1972, he became Marvel’s president and publisher.

Lee spent the 1970s fine-tuning his public persona as an amiable, all-knowing guide to comics. He spoke to the media and at venues across the country, from college campuses to convention floors, while defining the visuals of his one-man brand: thick mustache, gray-haired toupee, and tinted glasses. Internally at Marvel, though, he was facing rifts with artists and writers over everything from content to labor conditions. At one point, Lee’s old boss Martin Goodman and his son Chip formed a new, rival publisher and recruited top talent like Ditko and Larry to work on comics for them. Lee responded by sending his freelancers a letter that implored them not to contract with other companies. In it, he compared his competitors—including the Goodmans, who were Jewish—to Nazi Germany and Marvel to the Allies. He had gone “from being creative force to total company man,” in the words of Roy Thomas, his former assistant.

Lee was still dreaming of success elsewhere, brainstorming humor magazines, novels, and newspaper strips that were mostly dead ends. In 1980, he became the creative director of a new animation studio, Marvel Productions, and set out with his family for Los Angeles. But in Hollywood, he quickly found that many people in show business, among them the head of the studio where he worked, took little interest in him or his ideas, including those for movies based on Marvel characters. “You couldn’t give comic books away in those days, as far as properties,” the animation writer John Semper tells Riesman. “So, consequently, nobody really cared about Stan.” He had meetings, including with director James Cameron, about making live-action superhero movies but couldn’t land a deal. His pitch to adapt a Japanese TV show about a team of acrobatic heroes was rejected—only for someone else to do it years later and strike gold with Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. “I don’t understand why they don’t have any imagination,” Lee lamented to a friend. “I don’t understand why they can’t understand what I’m saying.”

These were, in retrospect, prescient proposals. Many of Lee’s later ideas were not. In the ’90s, Marvel declared bankruptcy and terminated Lee’s contract. He quickly negotiated and signed another one to serve as a figurehead, but soon after launched an internet start-up called Stan Lee Media with a man named Peter Paul. The enterprise was disastrous and short-lived: In addition to losing millions of dollars, SLM became the subject of an investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2001 after a precipitous stock price drop, resulting in the Department of Justice indicting Paul—who was now in Brazil—on charges of fraud. He was extradited, pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Lee and three others he’d worked with at SLM then formed POW Entertainment, which was, according to Riesman, “a largely criminal enterprise,” accused of an array of misconduct. It remains unclear how much Lee knew about or participated in the illegal activities of the two companies, but both were meant, at least putatively, to serve as platforms for the dissemination of his genius. This was manifested in uninspired endeavors like superhero versions of the pop group the Backstreet Boys, realized as a comic book and toys in Burger King kids’ meals; Stripperella, a TV show about a stripper/crime fighter voiced by Pamela Anderson; and a cartoon produced with Playboy titled Hef’s Superbunnies, which was never made.

Lee’s late-in-life projects came to varying degrees of fruition, but many were only ever announcements that generated hype, which may have helped fuel the fraud. Few, if any, were critical or commercial successes. Lee became even more recognizable during the aughts, but it wasn’t due to his own creativity. It was because his presence had become an exciting Easter egg in Marvel’s superhero movies, which, Riesman points out, took off “only after he had handed the reins to others.” The box-office boom started with Blade in 1998, the same year that Lee lost his company contract. His run of cameos began with the next movie, X-Men, in 2000.

While a person in his eighties can be forgiven for not managing to re-create the glories of his earlier career, the failures of Lee’s last two decades point to a through line in True Believer: The man hailed as brilliant had a lot of bad ideas, not simply in terms of marketing, but in content and execution. He was obsessed, for instance, with the idea of publishing collections of found images with comedic captions. (One example: a woman who stands beside Marilyn Monroe and exclaims, about her breasts, “They’re real!”). The concept is basically a proto-meme—which has potential. But for Lee it never landed, probably because the pairings were not funny.

In light of this, it’s only natural to ask: Could Lee really have invented all those Marvel characters on his own? Riesman doesn’t make a judgment either way, but I get the sense that he’s doubtful, as am I after reading his book. “Stan was a man whose success came more from ambition than talent,” he writes. Lee’s ambition was to reach the top, which he did thanks in large part to his skill at self-promotion and his charm.

You can see those qualities at work in interviews, where he comes across as genial, funny, and assured, speaking with a thick New York accent. In one from 2000 on CNN, Larry King introduces him as “the most famous name in American comic-book history” and goes on to ask, “What constitutes a hero?” Lee’s response harks back to the Marvel breakthrough of the ’60s: “Basically, to me, a hero is somebody who will sacrifice or will take great chances to help others but still have human traits, still not be perfect. When they become perfect, they become dull.”

The irony is that Lee could never adhere to his own definition. He rarely went out of his way to help others—whether they were his own workers vying for better conditions or Kirby trying to reclaim original art from Marvel in the 1980s—and he spent his whole life hiding and running from his own imperfections. The stories he told about himself were never as complex or compelling as those he wrote for his comic-book characters. The debut issue of Spider-Man famously depicts Peter Parker grappling with the results of his ethical choices: By not stopping a robber, he allowed that man to go on and kill his uncle. He is forced to confront the reality that “with great power there must also come—great responsibility!” as the oft-quoted line—written by Lee—goes.

By contrast, Lee’s 2002 memoir Excelsior! is, Riesman finds, “largely self-serving,” studded with lies that “reinforced Stan’s legend, and elided anything for which he might be found to be at fault,” including the fraud at SLM. The 2015 graphic novel adaptation of it is much the same, with a primary quality of tedious flatness. Poring through Lee’s archives, Riesman can’t find much in the way of genuine self-reflection, let alone suggestions of remorse. As a result, despite being well-researched and thorough, True Believer feels like it’s missing an emotional core, some sense of what the person at its heart, the real Stan Lee, was like. It seems that few people ever knew.

Lee may have done groundbreaking work, but his personal version of heroism was, at heart, old-fashioned: He envisioned himself as an icon who, by his own doing, redeemed some small part of the world. He believed not just in his own myth but in that of America: a place filled with well-intentioned, bootstrapping individuals who shape their own destinies. And the superhero genre, even Stan Lee’s version of it, propagates this national narrative, with its focus on strong men, its simplistic visions of good versus evil, and its glorification of justifiable violence.

Riesman dissected the problem in a review of the TV series The Boys for New York magazine: “The core pantheon of superheroes have always, always ended up upholding the status quo, and we are finally waking up to the fact that that status quo is morally indefensible.” While I take issue with his “we”—many people have long known the truth—the past four years have certainly driven home how much of the American dream is in fact a delusion. It’s one that Lee not only bought into but helped shape, seemingly without regret.