Donald Trump’s second impeachment trial is over, and Washington is now congealing around some sort of august body to investigate the January 6 insurrection. Earlier this week, Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced that she would support creating an “outside, independent 9/11-type commission” to investigate that fateful day’s events and the government response to it. Some House and Senate Republicans have also warmed up to the idea, especially where security failures are concerned.

A “9/11-type commission” is a slightly misleading name. Congressional commissions like the one that investigated the September 11 attacks existed long before 2001. And the 9/11 Commission was hardly an exemplar of the form. Its work was marred by internal struggles between Democratic and Republican members, and the commission’s efforts to probe government failures were often stonewalled by the George W. Bush administration, which had resisted its creation in the first place.

But the popular idea of the 9/11 Commission—a nonpartisan investigatory body that could definitively establish what went wrong and how to fix it—is alluring for a reason. If anything, that model shouldn’t only be used for the attack on Congress. With Covid-19 vaccinations on the rise and a possible end to the pandemic in sight, now would be an excellent time for lawmakers to create a similar commission to investigate how the U.S. failed in its response—and how it can do better next time.

When I first wrote about this idea last March, I identified three possible avenues of inquiry for such a commission. First and foremost at the time was the debacle over testing—or, to be more precise, the widespread absence of testing and the strict Centers for Disease Control and Prevention limits imposed on who could obtain it. Another issue is why the U.S. public health system wasn’t better prepared for the pandemic and whether those failures stem from Trump or from deeper institutional problems. Finally, there’s the question of the economic response: Did state and federal officials provide enough relief to those affected by the pandemic, and if not, what could they have done better?

Since then, a myriad of additional problems have cropped up. A Covid-19 commission could probe the decisions by public health officials initially to discourage mask-wearing, which has now come to be seen as vital in containing the virus’s spread. It could probe the weaknesses in the U.S. medical supply chain that affected everything from testing reagents to masks to ventilators, including whether Congress should mandate that certain products be made domestically from now on. It could explore widespread failures in data collection by public health agencies that had to be mitigated by journalists, academics, and other volunteers. The commission might be especially interested in why the United States excelled at creating a vaccine but struggled, at least initially, to distribute it.

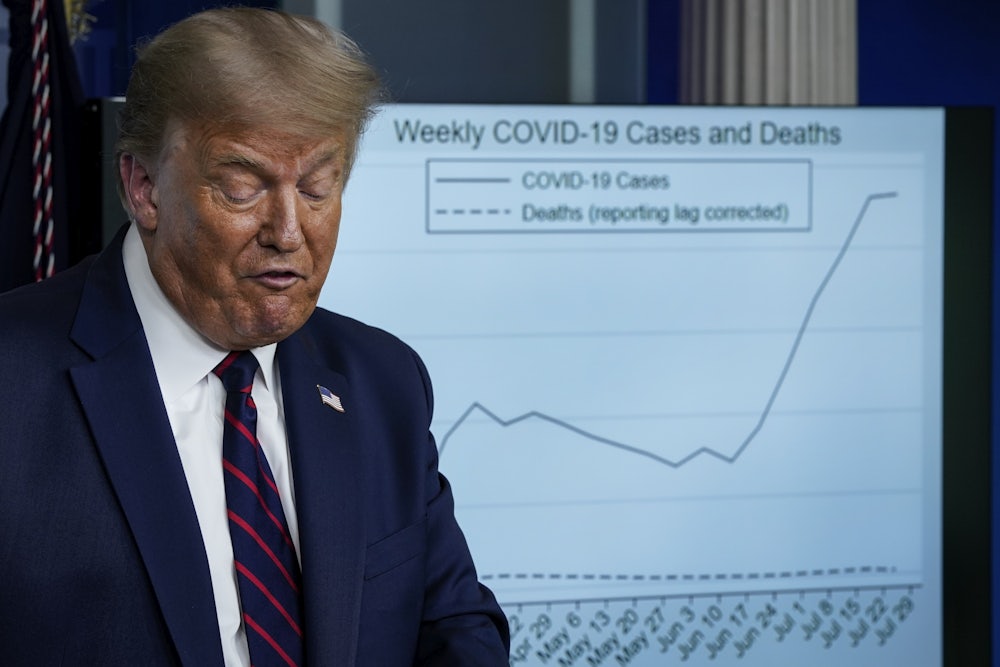

In some ways, the commissioners would have an easy job ahead of them. Most failures in the U.S. response to Covid-19 can be traced back to Trump himself. The former president was openly indifferent to the crisis even as government agencies and outside experts began sounding the alarm in early 2020. He dismissed early efforts to confront the virus’s spread as “alarmist” and publicly claimed it was no worse than the flu, even while privately admitting to Bob Woodward that he was downplaying its severity for political purposes. Countless other failures traced from Trump’s magical thinking and self-absorption: turning mask-wearing into a culture-war issue, dismissing efforts to fight it as a threat to his reelection, and pushing against expanded testing that would reveal its true extent.

But other aspects of the pandemic response are less clear from an evidence standpoint, or at least more obscured by the heat and immediacy of the moment. One of the most disruptive aspects was the school closures that forced millions of children to learn remotely for most of the last year. There is some evidence that the rapid closures of schools last March and April curbed the virus’s spread, potentially saving thousands of lives. At the same time, the closures may have had a dramatic effect on students’ academic performance and mental health, as well as their parents’ employment and well-being. A commission operating with the benefit of hindsight might be able to figure out what, if anything, the country could have done differently or better.

Support for creating a commission to review the pandemic response has only grown in recent months, as well. In December, Brookings Institution president John Allen and infectious disease expert William Haseltine noted in The Atlantic that the 9/11 Commission prompted Congress to make sweeping changes in the federal government after an attack that killed just shy of 3,000 Americans. “Covid-19 has already caused nearly 100 times as many deaths in the United States as 9/11 did. The need for prompt, decisive action is obvious.… One could argue that the danger of a new virus wasn’t fully appreciated in advance. In the future, we will have no such excuse.”

There is also already support for such a move from within Congress. Last year, Mississippi Representative Bennie Thompson and more than two dozen other Democratic House members introduced the Covid-19 Commission Act, which would have created a 25-member body with the power to issue subpoenas that could study the nation’s response to Covid-19 and propose recommendations for legislative changes and future response. A similar bill by California Representative Adam Schiff also drew support from more than a dozen House and Senate Democrats, including then-Senator Kamala Harris.

Who would lead such a committee and serve on it? Thompson’s bill would allow the chairs and ranking members of 15 different House and Senate committees to appoint members. Schiff’s bill would require its 10-member body to be chosen by party leaders in Congress, with the chair named by the president and the vice chair named by the Senate leader from the other party. Restricting it to people who have served in elected office but not during the pandemic would help provide a measure of objectivity. There is no shortage of possible candidates for the Democratic chair. One possible choice for the GOP vice chair would be Bill Frist, a former Senate majority leader and a physician who has urged elected officials, particularly fellow Republicans, to take greater steps to slow the virus’s spread.

What makes a commission most attractive, however, isn’t its own strengths but Congress’s weaknesses. Lawmakers could always create a special joint committee to review the national Covid-19 response, after all. But the legislative branch’s decline from a policymaking engine into a performative theater over the last 30 years makes this a fool’s errand. Its hearings would be arenas for grandstanding and score-settling; its reports would be hopelessly mired in partisan theatrics. Congressional reform is also an urgent task for lawmakers, but it shouldn’t stand in the way of answers about the pandemic response.

Indeed, if Americans are going to learn from what happened over the past year, a Covid-19 commission is not only essential but maybe even necessary. It might be darkly reassuring to think that what America endured over the past year stemmed only from the confluence of an incompetent president and a once-in-a-century event. But the best gift we could bestow on future Americans is to arm them for the possibility that such a pandemic will happen again—because it almost certainly will.