A former public affairs aide for the AFL-CIO once told me he spent most of his day fielding queries from conservatives. Most liberals outside the Rust Belt lost interest in organized labor decades ago; only now are they starting, tentatively, to think again about unions’ role in creating the sort of society they want. Conservatives, by contrast, never lost interest in “Big Labor” (as they insist on still calling it, even though that’s devolved into more of a taunt than description). Conservatives care about unions because the people who write checks for their movement never stopped wanting to finish off organized labor for good.

I share this observation by way of explaining my gratitude to the conservative press for keeping me up on labor news. I had no idea that President Joe Biden’s infrastructure bill was a stalking horse for the Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO, Act, a labor-reform bill that would repeal much of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, until I read about it on the website for Fox Business News: “Biden’s $2.5T infrastructure plan includes pro-union legislation.” “A significant component of the proposal,” reported National Review, “would eliminate the Right to Work legislation that has passed in 27 states, which gives workers the ability to refuse to contribute dues to their local union.” This last detail went missing in today’s lead stories in The New York Times and The Washington Post. Even the hyper-nerdy Vox left it out.

The fate of America’s infrastructure has never captured my imagination, maybe because I’ve heard that tocsin clang ever since Pat Choate first popularized the word in his 1981 book America In Ruins. (Back then, the collapse of the Mianus River Bridge along I-95 presaged imminent catastrophe from coast to coast.) I’m for public investment as much as the next guy. But the only infrastructure I know that has eroded steadily, chunk by falling chunk, over the past 40 years–to the point where today it only barely exists–is the American labor movement. If the infrastructure bill includes some or all of the PRO Act, then let the rebuilding begin.

Another thing to remember about the conservative press is that it tends to jump the gun. There is no infrastructure bill per se, just an outline furnished by the White House, and that outline says nothing about including any part of the PRO Act. (It does mandate that the infrastructure be built paying prevailing wage, which is mostly required anyway on federally funded projects.) The outline says that Biden is calling on Congress:

to ensure all workers have a free and fair choice to join a union by passing the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, and guarantee union and bargaining rights for public service workers.

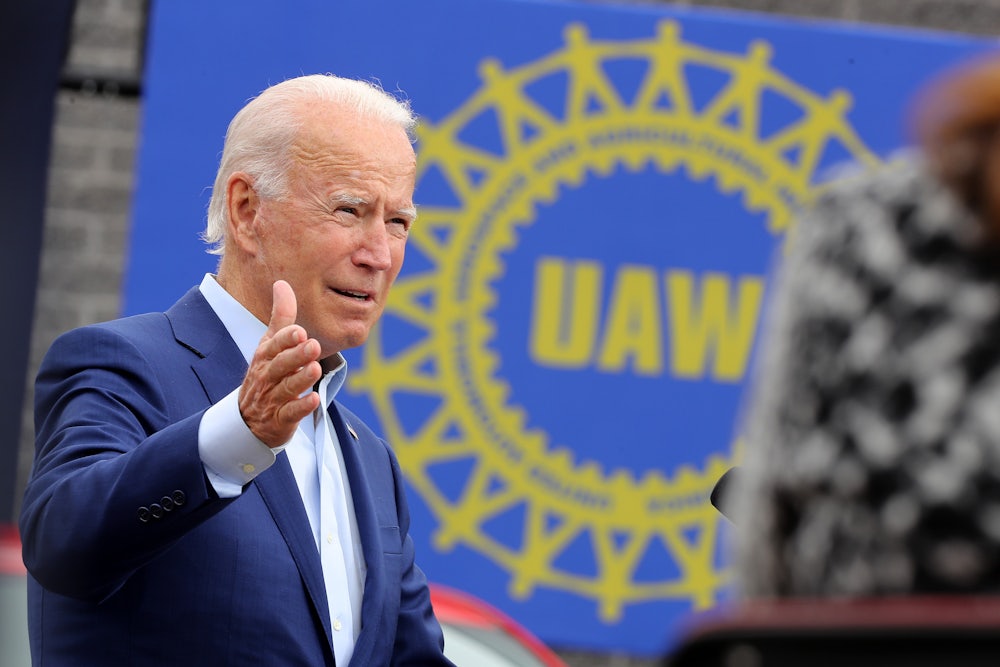

Similarly, a speech Biden gave on Wednesday to announce the infrastructure plan said only that he “asked Congress to pass the Protecting the Right to Organize Act—the PRO Act—and send it to my desk.”

Still, Fox Business News and National Review aren’t barking entirely up the wrong tree. The language in the outline and in Biden’s speech, which he delivered at a union-funded carpenters’ training facility in Pittsburgh, did signal that he’s thinking about including some PRO Act language in the bill.

The White House, I can confirm, is weighing this option. The infrastructure bill may include the PRO Act’s elimination of state laws that allow workers in an organized workplace to refuse to pay union fees while still enjoying the fruits of collective bargaining. These so-called right-to-work laws create a free-rider problem, because the union is legally required to represent every worker in its unit, regardless of whether he or she pays a membership or “fair share” fee.

Such laws have long been a priority for anti-union business groups as an efficient way to weaken unions’ membership and finances. Most right-to-work laws were passed in the decade or so after enactment of the anti-union Taft-Hartley law of 1947, which made this arrangement legally permissible. But in the past decade, as Republicans greatly expanded their control of state legislatures, the laws have enjoyed a revival, with five states since 2012 adopting them, all in or near the industrial Midwest.

Another provision under White House consideration for inclusion in the infrastructure bill is some or all of the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act, which would allow the federal government to impose on states a minimum standard for state and local employees’ collective bargaining rights. This bill was introduced in reaction to the Supreme Court’s anti-union ruling in Janus v. AFSCME in 2018, which required all state and local government employee unions to follow right-to-work rules. The plaintiff in the case, Mark Janus, was a child support specialist in Illinois who didn’t want to pay a fair-share fee to the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, which Janus didn’t join. After he won his case, which of course was bankrolled by right-to-work groups, Janus showed his gratitude to the high court by quitting his state job and going to work for the anti-labor Liberty Justice Center.

A third PRO Act provision that the White House may fold into the infrastructure bill would allow the National Labor Relations Board to impose fines on employers who violate labor laws. Incredibly, the NLRB may currently require only that these scofflaws furnish back pay. That goes a long way toward explaining why businesses don’t take such violations terribly seriously. As Marianne LeVine reported three years ago in Politico, compliance with minimum wage and overtime laws is, in many states, effectively voluntary.

Inclusion of any of these provisions would obviously make the infrastructure bill, which already faces an uphill battle, even harder to pass. If the Democrats decided to avoid a Senate filibuster by making it a “reconciliation” bill, as happened with the Covid-19 stimulus, then only the NLRB fines could be folded in. There’s a decent chance that the Democrats’ maddening fence-sitter, Senator Joe Manchin, would go for it. West Virginia is one of the states that went right-to-work in the past decade, but Manchin didn’t support that, and he tends to vote with organized labor (which still has some political clout in that coal-mining state).

It’s a hobby of mine to count Republican votes on labor bills. Although the party as a whole is unambiguously anti-labor, some Republican legislators nonetheless vote pro-union. About one-third of union members vote Republican in presidential elections—don’t ask me why—and that doesn’t entirely escape notice in Congress. When the House passed the PRO Act on March 9, the Democrats picked up five Republican votes (and lost one Democrat, Representative Henry Cuellar of Texas). Five Republican votes for the PRO Act is better than the three House Republicans who, in a 2019 vote, supported raising the minimum wage to $15.

As I’ve noted elsewhere, repealing Taft-Hartley has been a Democratic fantasy for 73 years. Even Lyndon Johnson couldn’t do it during his Great Society heyday. Yet there are today more Republican votes to do that than there are to raise the minimum wage, something Congress managed to do 26 times since Taft-Hartley became law. Obviously, raising the minimum wage has gotten harder in recent decades, but do you doubt that eventually the Democrats will raise it? Maybe a labor rights bill will start to feel inevitable, too.