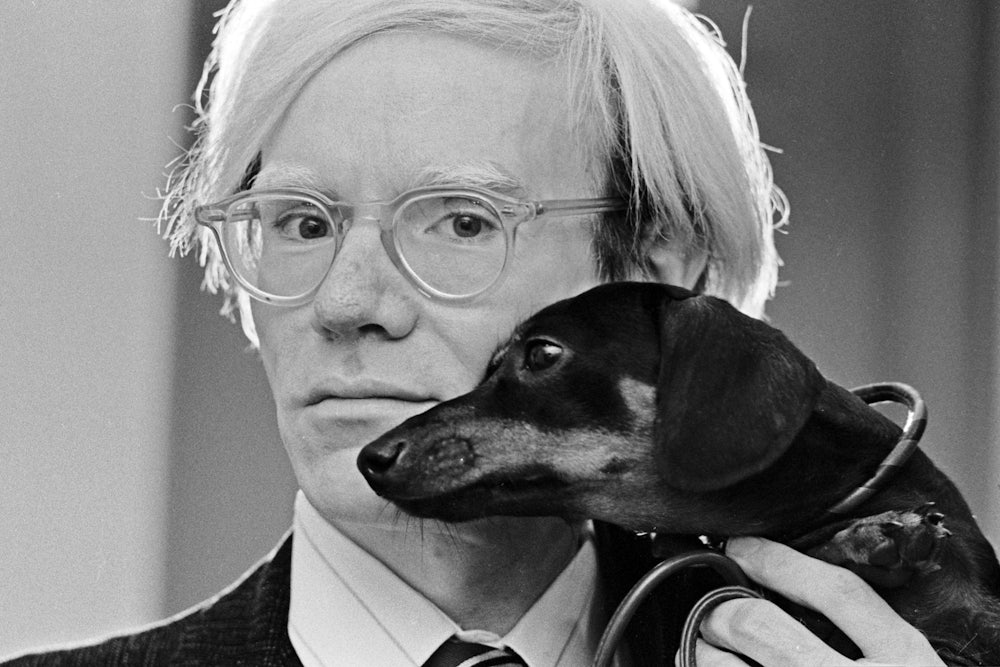

The Supreme Court, which is no stranger to the big questions of American life, took up a sizable one on Monday: What is art? The case, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith, centers around a dispute over whether the pop-art legend violated a photograph’s copyright when creating one of his iconic tableaus of modern celebrity. Resolving it will require answering a host of interesting questions: Where does copyright end and the First Amendment begin? When is a work of art simply derivative, and when is it truly transformative?

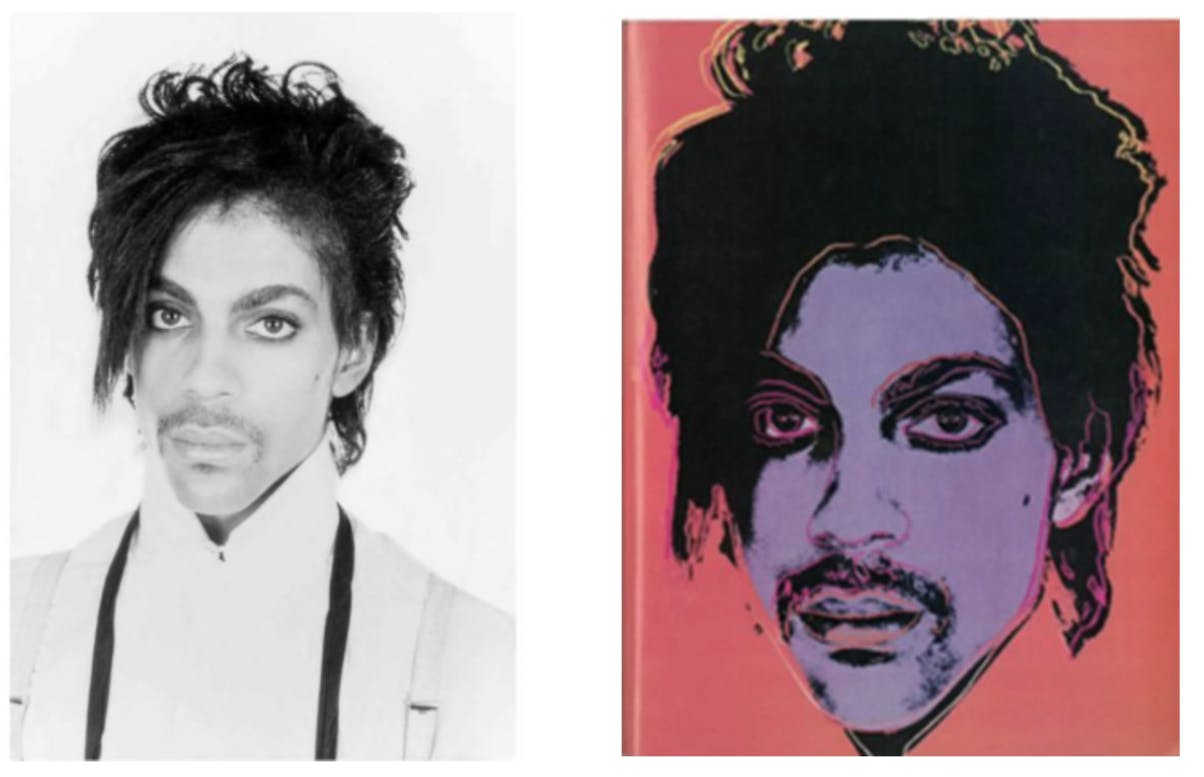

Lynn Goldsmith, a photographer and musician herself, started a successful photo agency in the 1970s that specialized in musicians and album covers. In 1984, her agency licensed one of Goldsmith’s photographs of Prince—a humane, moody portrait of the Minnesota musician at the early height of his stardom in 1981—to Vanity Fair for use as a reference in an illustration. Vanity Fair passed along the photograph to Andy Warhol, who used his signature silk-screening process to create a new version of the original image. Vanity Fair used that version in one of its print issues and credited it to Goldsmith and her agency. Warhol also created more than a dozen other new works from the original photograph, which became known as the Prince Series in the art world.

Goldsmith claimed she was unaware that Warhol had worked on the Vanity Fair image and that he had then created further works with it. The two sides of this case might have passed each other like ships in the night if Prince had not suddenly died in 2016. After his death, Vanity Fair reproduced one of the Warhol versions for its memorial cover for the singer. That drew the attention of Goldsmith and her agency to Warhol’s Prince Series for the first time, and they contacted the Warhol Foundation and threatened legal action. In response, the foundation sued Goldsmith in federal court to obtain a ruling that it hadn’t violated any copyright laws.

The foundation argued that Warhol’s use of the photographs fell under the category of “fair use,” a concept in copyright law that allows people to use copyrighted works without risk of infringement. Fair use is a simple idea in theory with a healthy amount of complexity in practice. Federal law sets out four factors for courts to consider when weighing fair use claims: the “purpose and character” of the use, the nature of the original work, the amount of the work used, and the impact on future marketability for the original work.

Warhol, notably, used Goldsmith’s photograph for an entire series of works, which his foundation has in turn licensed and merchandized. The foundation argued that this still counts as fair use because of the “transformative” nature of Warhol’s work. The Supreme Court has previously explained that transformativeness can insulate partially copied works from violations. “In the context of fair use, we have considered whether the copier’s use ‘adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering’ the copyrighted work ‘with new expression, meaning or message,’” Justice Stephen Breyer wrote last year in the court’s ruling in Google v. Oracle, which involved the application of fair use to computer code.

To the foundation, Warhol’s process in creating the Prince images meets that threshold. “Warhol cropped the image to remove Prince’s torso, resized it, altered the angle of Prince’s face, and changed tones, lighting, and detail,” the foundation explained in its petition. “Warhol also added layers of bright and unnatural colors, conspicuous hand-drawn outlines and line screens, and stark black shading that exaggerated Prince’s features. The result is a flat, impersonal, disembodied, mask-like appearance.”

Warhol himself repeated this process 15 times with the same image, sometimes leading to significant differences between each of the works. “That process, as the district court aptly found, ‘transformed’ Goldsmith’s intimate depiction” in order to “comment on the manner in which society encounters and consumes celebrity,” the foundation argued. Twelve of the original 16 images have been sold to collectors, and four are in a museum; each of them is licensed out by the foundation for various purposes.

Goldsmith, in response, argued that the image’s essential mystique still derived from her photography work, not from Warhol’s alterations of it. “Warhol kept the same angle of Prince’s gaze,” she told the justices in her filings. “He reproduced the shadows ringing Prince’s eyes and darkening his chin. Warhol replicated the same dark bangs partially obscuring Prince’s right eye. Warhol even copied the light and shadow on Prince’s lips, which owe their pattern to the gloss that Goldsmith asked Prince to apply. Even the reflections from Goldsmith’s photographer’s umbrellas in Prince’s eyes remain visible in Warhol’s series.”

A federal district court in New York sided with the foundation in 2019. “The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” Judge John Koeltl wrote in his ruling. “The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince—in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

At this point you might be wondering why Warhol hasn’t run into legal issues before. There are two answers here. One is that his most iconic works, including the aforementioned pieces referenced by Koeltl, used works that were unlikely to face similar litigation. His Marilyn Monroe photographs are derived from a publicity still. His Mao series came from a photograph taken by a government photographer long before the People’s Republic of China reintroduced copyright laws in the 1990s. And Campbell’s Soup Company appears to have accepted Warhol’s use of its iconic design. When the company announced it would release limited-edition cans in 2012 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Warhol’s Campbell’s series, the company noted that it had licensed the images from the Andy Warhol Foundation.

The other answer is that Warhol’s works have actually faced copyright battles before. In 1996, photographer Henri Dauman and Time Inc. sued Warhol’s estate over a photograph taken by Dauman of Jacqueline Kennedy at her husband’s funeral in 1963 for Life magazine. Warhol had used it to create his Sixteen Jackies series in 1964. The two sides reportedly settled the lawsuit for what one lawyer told the Los Angeles Times was “several hundred thousand dollars.” Warhol himself settled a similar lawsuit brought by photographer Patricia Caulfield after she sued him for using one of her photographs to create his 1964 work Flowers.

Goldsmith asked the Second Circuit Court of Appeals to review Koeltl’s decision. In November 2019, a three-judge panel overruled the lower court and sided with Goldsmith. It concluded that Koeltl had erred by focusing on the aesthetic nature of whether Warhol’s work was “transformative” for fair use purposes. “While the cumulative effect of [Warhol’s] alterations may change the Goldsmith photograph in ways that give a different impression of its subject, the Goldsmith photograph remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built,” Judge Gerald Lynch wrote for the panel. The appeals court also knocked Koeltl’s analysis that the Prince Series was instantly recognizable “as a Warhol,” arguing that this would amount to a “celebrity-plagiarist privilege.”

The foundation turned to the Supreme Court, asking it to overturn the Second Circuit’s ruling against it. It claimed that the panel had misread the court’s precedents on transformative works, including the then-recent Google v. Oracle decision, and had imposed a new test with broad ramifications for artistic works. “The Second Circuit’s visual similarity test undercuts the core purpose of the fair use doctrine, which is to protect the rights of innovators to create new works building—even heavily—on the insights as well as the imagery of others,” the foundation told the justices. “Artists routinely draw inspiration from both the form and substance of earlier works across a wide variety of artistic media.”

If the Supreme Court upholds the Second Circuit’s approach to fair use, it could have significant implications for works of art that draw upon copyrighted works. That, in turn, would have First Amendment implications for free speech and expression. “Courts cannot protect the First Amendment value of a Warhol work, or many other works of art, by looking only at their surfaces and disregarding underlying meaning,” a group of art law professors argued in an amicus brief urging the court to take up the case. The foundation warned that the Second Circuit’s approach would threaten to “strip protection from thousands of storied works of art and to chill expressive activity and artistic creation.”

In a way, it is all too fitting that Warhol’s works would be at the center of this case. His art often sought to challenge and capture American ideas of fame and celebrity, which, ironically enough, made him one of the most recognizable artists of the twentieth century. That some of his most well-known compositions came from the work of photographers, designers, and artists who did not become household names like him is an ironic undercurrent to his career. The Supreme Court won’t decide what that dissonance says about Warhol’s legacy or artistic vision. But it will consider this fall the extent to which the foundation that bears his name can make money from it.