Hate is as much a part of our American experience as the struggle for equality that often provokes it. Justice, which has too often been far from blind, has failed too many victims of hate. But we have a beacon of light in dark times. President Biden has signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, which came to his desk with the all too rare bipartisan support we need more of where justice and democracy are concerned. It also comes at a time when it could not be more critical to our democracy to take a unified stand against hate.

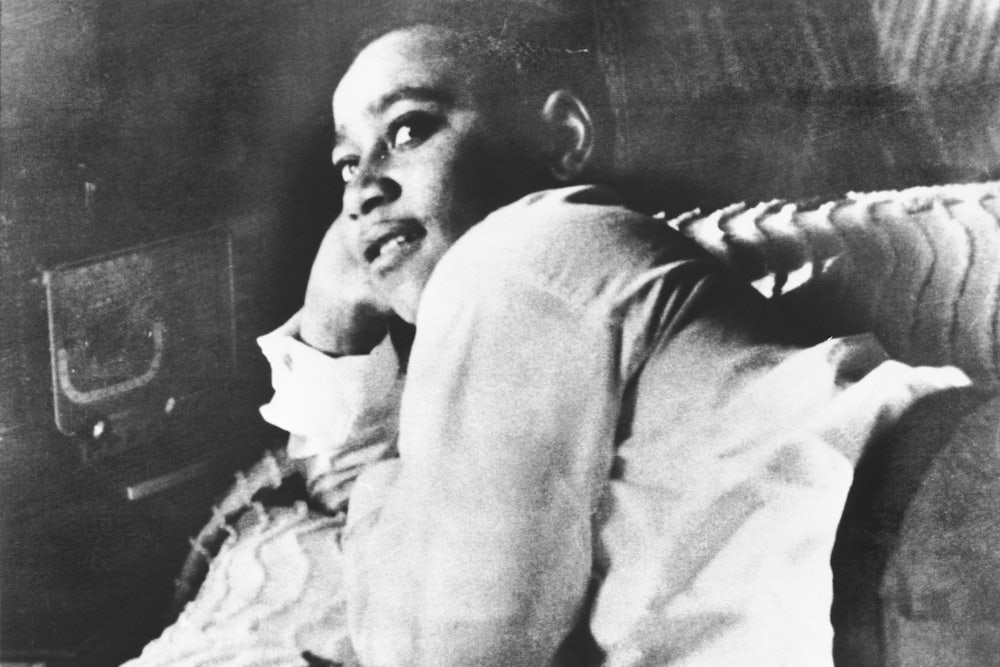

The family of 14-year-old Emmett Till, who, in 1955, was kidnapped and brutally murdered by white men for the “crime” of whistling at and allegedly grabbing a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, never received justice. It was a violent, brutal, and racist murder of a defenseless child, a Black child. His killers were acquitted by a jury of their peers (that is, white men), and years later Bryant would admit that Till didn’t touch her. This and many other racially motivated murders provoked a century of struggle for federal justice and anti-lynching legislation.

It is easy to believe that in our modern society, the story of Emmett Till is the shameful but distant past. But as Biden pointed out when he signed the bill into law, Ahmaud Arbery, the jogger who made the mistake as a Black man of stopping to look at a residential construction site, as some white people had done before him without incident, could not do the same without penalty of death. Three white men chased him and cut him off, and one of the three shot and killed him. The racist rants that federal prosecutors later shared in text messages and other communications made clear that Arbery was a victim of a hate crime. But they were not charged with a conspiracy to lynch Arbery. They were each individually charged with aiding and abetting one another. Now, thanks to this new anti-lynching law, prosecutors can charge conspiracy to commit hate crimes, and these crimes can be called what they truly are: lynchings.

Hate crimes are a national scourge and have been on the rise, including anti-Black hate crimes. The Justice Department reported that in 2020 about 3,000 victims of hate crimes were Black, up a whopping 49 percent from 2019. More disturbing, the number of hate crimes jumped even though the number of law enforcement agencies reporting them dropped by more than 400. That means the numbers are likely much higher. Astonishingly, only about 10 percent of police departments report hate crime data to the feds.

While Black people represent the greatest number of victims of hate crimes, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act is also vitally important for people of all races, for people of the Jewish faith, for Muslims and Sikhs, for women, transgender people, and people with disabilities. That’s because a neo-Nazi mowed down Heather Heyer at the horribly antisemitic and racist Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. Yao Pan Ma, a 61-year-old Chinese man, was brutally beaten and died, in April 2021 in New York City, in what has been charged as a hate crime. These stories of random terror are their own type of pandemic. In 2009, Congress passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act, a federal law expanding hate crimes to include crimes motivated by gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability. Solely because he was gay, Shepard was kidnapped, driven to a remote area, severely beaten and left to die.

At a time when teachers in Florida are told they can’t say “gay” and when books on racism, slavery, and the Holocaust are being banned, we are losing tools to promote understanding and also tolerance that can help counter the culture of hate that is seeping into mainstream media on shows like Tucker Carlson’s on Fox News, where he has parroted the language of antisemitic hate groups.

This nation has been divided by hate, and democracy has been upended by it. We should not forget the leaders and members of the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers—hate groups that have now had a civil jury verdict against them under a law known as the Ku Klux Klan Act for the hateful violence and intimidation in which the Charlottesville Unite the Right Rally engaged—have also been prosecuted for violent attempts to prevent the peaceful transfer of power after the 2020 election. While the Southern Poverty Law Center has reported a drop in the number of hate groups in the United States for the third year in a row, it has also pointed out that hateful views are more mainstream and therefore individual actors like Dylann Roof, who killed the pastor and nine parishioners of Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, can still be influenced by the ideology and the mainstreaming we have seen in our politics and state laws and school boards trying to prevent education and learning around everything from gender identity to racism.

This new anti-lynching legislation was an all too rare and rightly celebrated bipartisan bill, co-sponsored by Senators Cory Booker and Tim Scott, which had been co-sponsored by Vice President Kamala Harris when she sat in the Senate. Democracy cannot survive for any of us if we turn a blind eye to hate against anyone. But as we celebrate, we should not stop here. Remember, 90 percent of police departments in this country do not report hate crimes to the Department of Justice because it’s not required. We must require it to better understand whether we are succeeding at rooting out hateful violence and targeting resources where needed. Second, we need to ensure that the DOJ has the resources it needs to pursue federal hate crimes. Between 2010 and 2018, federal prosecutors brought only about 100 hate crime cases. We also need more resources for prevention of hate crimes and for community-based victims’ services so victims can get the help they need, along with support around reporting cases. Let us celebrate this historic step by ensuring the success of this important new law.