In the wake of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade in June, many Republicans have sought to avoid inflammatory rhetoric on the topic of abortion, particularly following Democratic victories in special elections and ballot measures that have hinged, in part, on support for abortion rights. Some Republican candidates have even tried to downplay their position on abortion, scrubbing their websites of more hard-line language.

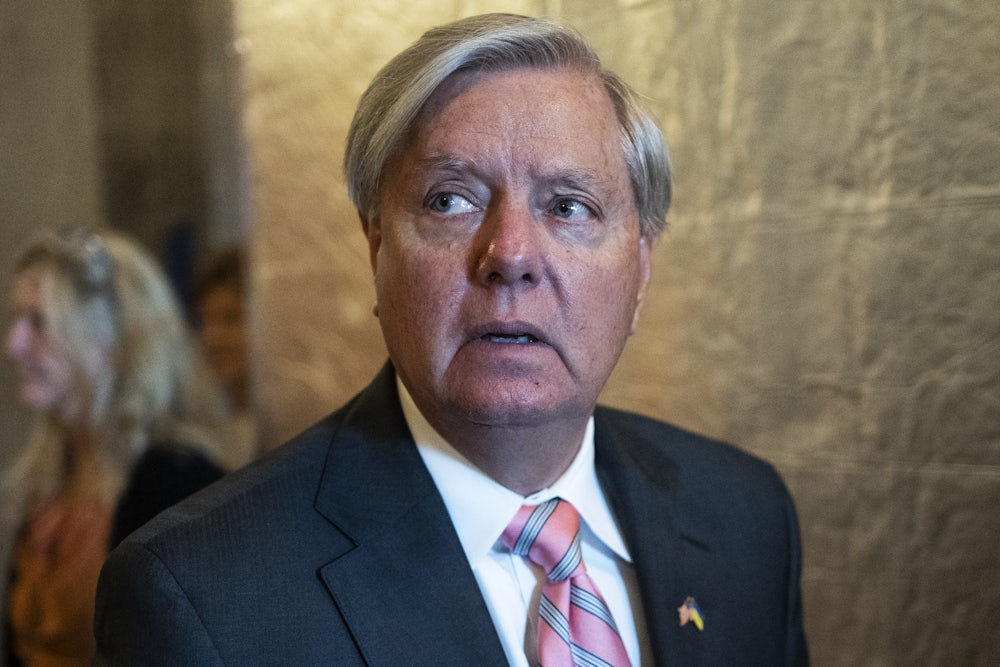

So when Senator Lindsey Graham introduced a measure that would ban most abortions at 15 weeks of pregnancy, some Republicans reacted with chagrin. Graham’s legislation is similar to previous iterations of the same bill, only with the cutoff starting at 15 weeks instead of 20. It would make exceptions for rape and incest—although it imposes reporting restrictions for these cases—as well as for life endangerment, although it notes that this caveat does not include “psychological or emotional conditions.”

With President Joe Biden in the White House and Democrats still in control of Congress for the time being, Graham’s bill has no chance of passing anytime soon. However, Graham’s proposal is out of step with medical consensus and the conditions that cause many to seek abortions in the first place—which may spark an uncomfortable conversation on the matter of reproductive health, as well as some clarification of why people seek abortions later in pregnancy in the first place.

Flanked by representatives from anti-abortion groups including March for Life and the Susan B. Anthony List, Graham held a press conference on Tuesday touting the bill. (He had previously said that he believed abortion policy should be left to the states.) The South Carolina Republican told reporters that he had decided to revise the legislation from banning most abortions at 20 to 15 weeks because “the science tells us the nerve endings are developed to the point that the unborn child feels pain.”

Not exactly: There is no scientific consensus on whether and when fetuses begin to feel pain, and experts say that the 15-week threshold is not based on medical evidence. In a statement, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said that the bill “is predicated on false claims of gestational development of pain response, propagates inflammatory rhetoric, and represents another callous example of governmental intrusion into the practice of medicine.” The state law that the Supreme Court upheld in the case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe, was a 15-week ban on most abortions.

Many Senate Republicans shied away from Graham’s proposal, demurring that abortion should be an issue left to the states. Senate Minority Leader McConnell told reporters on Tuesday that most Republicans “prefer this be handled at the state level.” Graham said Wednesday that he did not seek McConnell’s permission to introduce the bill, but predicted to reporters: “I think he would support it if it came to the floor.”

Here, again, Graham may be misreading the consensus—perhaps there could be Republican support for that proposal, but not necessarily weeks before a critical election. “I don’t think there’s much of an appetite to go that direction,” Senator Shelley Moore Capito told Politico. The reception was slightly warmer in the House, where Republicans have their own 15-week abortion ban with dozens of co-sponsors, including Republican Conference Chair Elise Stefanik. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has previously expressed support for a 15-week ban.

Meanwhile, Democrats pounced on Graham’s legislation, avowing that it represented the mainstream Republican position. “There are those in the party that think life begins at the candlelight dinner the night before,” Speaker Nancy Pelosi scoffed.

Democratic candidates immediately began hitting their opponents on the legislation; Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer warned on the Senate floor that “while Democrats want to protect a woman’s freedom to choose, MAGA Republicans want to take that right away”; the White House press secretary denounced it as “radical” in a statement.

“If we take back the House and the Senate, I can assure you we’ll have a vote on our bill,” Graham said on Tuesday, a promise that may soon be coming to a Democratic candidate’s TV ad near you. “If the Democrats are in charge, I don’t know if we’ll ever have a vote on our bill.”

But amid the political sturm und drang, the nuances of what such legislation would mean for people seeking abortions can be missed. The vast majority of abortions occur during the first trimester. Fewer than 10 percent take place between the fourteenth and twentieth weeks of pregnancy, and just 1 percent are performed on or after the twenty-first week. Medical experts also tend to avoid the phrase “late-term abortion”; as a term pregnancy can last between 37 and 42 weeks, an abortion that took place in the second trimester, for example, would definitionally not be late-term.

Graham’s legislation would allow abortions in cases where “in reasonable medical judgment, the abortion is necessary to save the life of a pregnant woman whose life is endangered by a physical disorder, physical illness, or physical injury, including a life-endangering physical condition caused by or arising from the pregnancy itself.”

But there could be a vast interpretation of what “in reasonable medical judgment” does or does not allow. Physicians may differ on when a situation becomes life-threatening or hesitate to take decisive action if a quick decision places them in some legal gray area.

“There are physicians throughout the United States who are having to consult with lawyers, for example, to decide what the cutoff is,” said Selina Sandoval, a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health and a practicing ob-gyn and complex family planning specialist. “So if I can keep a patient alive with blood transfusions, for example, how many blood transfusions do I need to do before I’m OK to do the abortion without losing my license and going to jail? Or if a patient’s infected, do they just need to be on antibiotics? Do they need to be septic? Do they need to be in the ICU? At what point can I intervene?”

In cases where abortions took place later in the pregnancy for reasons other than fetal anomaly or life endangerment, some research suggests that the woman may not have been aware that she was pregnant for the first few weeks of her pregnancy. A 2013 study found that women who sought later abortions were far more likely to have been pregnant for eight weeks or more before they discovered their pregnancy than women who received first-trimester abortions. This study also found that, compared to women who received first-trimester abortions, women seeking abortions between their twentieth and twenty-eighth week of pregnancy were generally younger, less likely to be married, less likely to have private insurance, and more likely to have traveled long distances to arrive at the abortion clinic. (Another study from March of this year found that while at-home pregnancy tests are associated with earlier pregnancy confirmation, adolescents in particular face barriers to obtaining at-home testing.)

“There are many fewer providers later in pregnancy. It is more expensive. Because there are fewer providers, there’s generally more distance needed to travel, which includes other financial costs and logistical costs,” said Katrina Kimport, a co-author of the 2013 study and a professor with the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health program at the University of California San Francisco. “There’s a way in which later recognition of the pregnancy can snowball into even later presentation for abortion care.”

Sandoval cited the Turnaway Study, landmark research led by Diana Greene Foster, which found that women who sought but were unable to receive an abortion were more likely to live in poverty, struggle with mental health issues, and remain in abusive relationships.

“These risks affect not just the pregnant person but also their families, because their children can get stuck in those cycles of abuse or poverty as well,” Sandoval said. “About two-thirds of patients that are presenting for an abortion already have children at home. And a lot of those patients are saying, ‘I’m having an abortion today so that I can better care for my children that I have.’”

Another report by Kimport released in April of this year studied the circumstances under which women sought pregnancy specifically in the third trimester. Some women seek abortions later in pregnancy due to new information that they could not learn until the third trimester, such as certain fetal anomalies or even the fact that they are pregnant. Several serious conditions, such as a fetus developing without a brain or congenital heart problems, cannot be detected until the ultrasound that takes place between 18 and 22 weeks.

Other women receive abortions in the third trimester because of barriers to obtaining one, such as financial obstacles, long-distance travel, or even domestic abuse situations. Ironically, policies to ban abortions earlier in pregnancy could contribute to an increase in later procedures, because women need to travel out of state, and the influx in demand could lead to longer wait times.

One woman whom Kimport interviewed had hoped to continue her pregnancy but discovered significant fetal anomalies at 21 weeks. But because her providers declined to perform an abortion, she had to travel out of state to find a clinic—which entailed significant travel, finding childcare for her son, and getting time off from work—meaning that she could not obtain an abortion until she was 24 weeks into her pregnancy.

Kimport told me that some people whom she interviewed experienced deep trauma when they realized their pregnancy was nonviable, meaning that the fetus would be unable to survive. Some sought an abortion to “end the suffering” for the unborn child they already called their “baby,” Kimport said. Graham’s legislation does not include exceptions for fetal anomalies or inviability.

“To be required to continue a pregnancy that somebody knows is nonviable, that somebody knows might entail suffering.… I think many Americans would be shocked that such a person would be required to continue the pregnancy,” Kimport said.

Democrats currently control both houses of Congress, so Graham’s bill is going nowhere in a hurry. But as Graham noted in his press conference, many Americans support some restrictions on abortion; polling demonstrates that people have conflicting views on whether abortion should be legal at later stages in a pregnancy. However, an August poll by The Wall Street Journal found that support for a 15-week ban dropped after the Dobbs decision.

At Graham’s press conference on Tuesday, one woman stood to describe her experience of finding out her unborn son had a fetal anomaly at 16 weeks, then giving birth to the baby and seeing him die shortly afterward. “I had regular appointments, I did everything right,” said the woman, whom The Washington Post identified as Ashbey Beasley. “When he was born, he lived for eight days. He bled from every orifice of his body, but we were allowed to make that choice for him. You would be robbing that choice from those women. What do you say to someone like me?”

Graham insisted in the press conference that, if the Senate was able to debate the bill, “we will do really well with the American people.” When I asked Graham on Wednesday if he would be open to carving out an exception for fetal anomalies, he replied: “If that would help us get over the line, I might be.”

Kimport noted that many of the people to whom she has spoken understood that abortion in the third trimester could be prohibited in their state but believed that any exceptions applied to their cases, and then were surprised when they did not.

“What I think that illustrates is that the universe of different possible things that can happen during a pregnancy far exceeds our ability to write a law that draws a line between one situation and another, and a line that broadly everybody agrees with,” Kimport said.