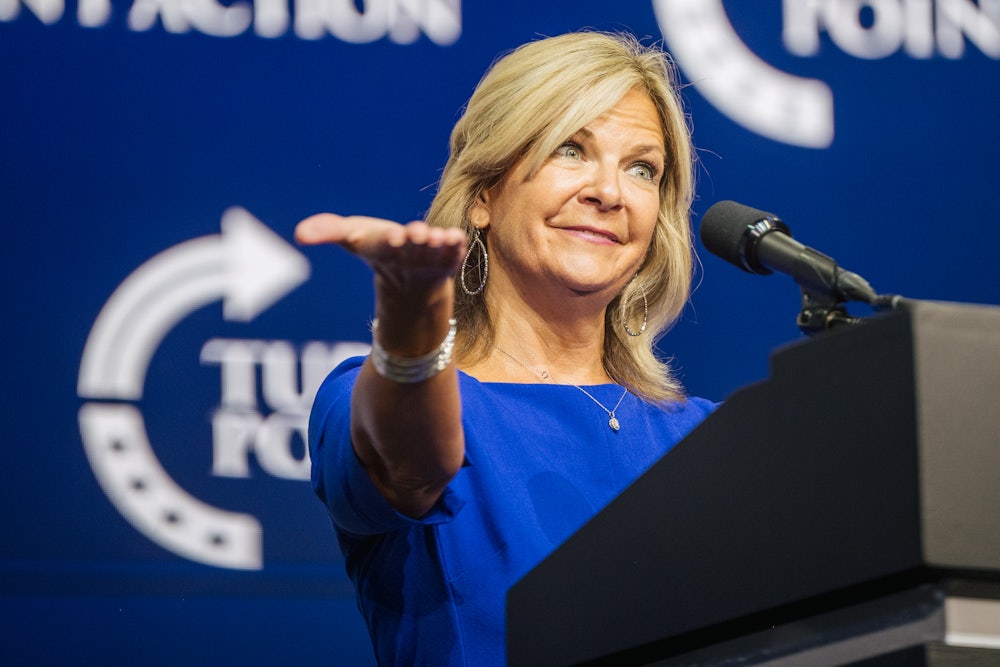

The Supreme Court declined on Monday to block the House January 6 committee from obtaining the phone records of Kelli Ward, the Arizona Republican Party chair, as part of its investigation into the attack on the Capitol last year. Ward and others had asked the court in October to block the subpoena for allegedly violating her constitutional rights, including her First Amendment right to free association.

“This is an unprecedented case with profound precedential implications for future congressional investigations and political associational rights under the First Amendment,” Ward told the court. “In a first-of-its-kind situation, a select committee of the United States Congress, dominated by one political party, has subpoenaed the personal telephone and text message records of a state chair of the rival political party relating to one of the most contentious political events in American history—the 2020 election and the Capitol riot of January 6, 2021.”

The justices did not delineate why they rejected Ward’s request. The motion came to them through the court’s shadow docket for emergency petitions, where the court does not usually explain its reasoning. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, who signaled that they would have granted Ward’s motion, likewise did not lay out their reasoning. The justices are not required to indicate which way they vote on shadow-docket motions, so it is possible that others voted the other way as well.

That absence of information can make analyzing the court’s shadow-docket decisions tricky, but that silence can be telling in other ways. The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has often been skeptical of Congress’s investigatory powers in general and often delivered rulings to that effect during the Trump era. And yet the court has taken no action thus far that would hinder inquiries into the January 6 attack or other 2020 election issues, perhaps reflecting that it understands the gravity of that matter.

The court’s first encounter with the topic came last December. Trump had sought to block the National Archives from turning over White House records to the January 6 Committee by invoking executive privilege. President Joe Biden, the actual executive, had signed off on the release. Both a federal district court and the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Trump’s argument by noting, among other reasons, that the former chief executive could not countermand the actual president on when executive privilege could be invoked.

In response, the high court took the rare step of writing about its reasoning. The justices denied Trump’s request but also made an unusual effort to limit the scope of the lower courts’ ruling. The unsigned opinion noted that the dueling executive privilege claims between a current and former president “are unprecedented and raise serious and substantial concerns.” At the same time, the majority noted, the D.C. Circuit had concluded that Trump could not invoke executive privilege in this case even if he were the sitting president. “Any discussion of the [D.C. Circuit] Court of Appeals concerning President Trump’s status as a former president must therefore be regarded as nonbinding dicta,” the court concluded.

It’s hard not to read that as the result of a compromise between the court’s internal factions. At least one justice indicated that he thought former presidents could invoke executive privilege after leaving office. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who worked in the White House counsel’s office during the second Bush administration and is more familiar with executive privilege than the other justices, wrote separately to opine on the virtues of reading this power broadly. But he nonetheless joined the majority because it had lopped off the portions of the D.C. Circuit ruling that would have narrowed the privilege. Only Thomas indicated that he voted the other way.

The next constitutional question to arise from Trump’s effort to overturn the election came in October. Local prosecutors in Georgia had sought to question South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham about his role in an alleged pressure campaign for state election officials to tip the election in Trump’s favor. The Washington Post reported shortly after Election Day that Graham had called Brad Raffensperger, Georgia’s then secretary of state, and asked him whether he had the power to toss out all ballots in certain counties if a certain number of signature-matching errors were found. According to the Post, Raffensperger interpreted Graham’s question as a suggestion to throw out lawful ballots.

Graham filed a lawsuit to block the subpoena, citing the Constitution’s speech and debate clause. The clause generally says, among other things, that members of Congress “shall not be questioned in any other Place” for what they say in an official capacity. Graham argued that he was protected from the grand jury’s questioning because he was acting as a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time. A federal district court in Atlanta ruled that he could not be questioned on some topics but said that others were fair game, including his communications with the Trump campaign and whether he had “cajoled” local election officials to do anything.

The justices again declined to intervene and again took steps to limit the scope of what could happen. In an unsigned opinion, the court emphasized that the lower courts had assumed that Graham’s “informal investigative fact-finding” was protected by the clause and that he could not be questioned about it. “The lower courts also made clear that Senator Graham may return to the District Court should disputes arise regarding the application of the Speech or Debate Clause immunity to specific questions,” the court added. “Accordingly, a stay or injunction is not necessary to safeguard the Senator’s Speech or Debate Clause immunity.”

In Monday’s case, Ward drew upon a recent Supreme Court ruling that took a more skeptical view of congressional investigations. In the 2020 case Trump v. Mazars, the former president tried to block the House Oversight Committee from obtaining his financial records from his accounting firm at the time. Trump argued that the inquiry violated the constitutional separation of powers and that it was an impermissible use of congressional oversight powers to examine his personal financial records. The committee said it needed to obtain the records for legitimate legislative reasons.

The court did not embrace Trump’s call to radically narrow congressional oversight powers. But it did impose a set of guardrails on when Congress could subpoena the president himself for private nonofficial records. In a four-part test to guide the lower courts, Chief Justice John Roberts noted that the “burdens imposed by a congressional subpoena should be carefully scrutinized, for they stem from a rival political branch that has an ongoing relationship with the President and incentives to use subpoenas for institutional advantage.”

The court’s seven-justice majority in Mazars thus found a way to narrow Congress’s investigatory powers against the president without handing Trump a direct win. Thomas and Alito wrote separately to say that they would have gone even further to limit congressional authority in this sphere. Those same two justices dissented when the court rejected Ward’s plea on Monday.

I’ve noted before that, despite Trump’s consistent belief to the contrary, the Supreme Court has only rarely intervened in his favor over the last six years. That misperception of the court’s conservative majority might also now be shared by his fellow election deniers and hangers-on. What’s telling in many of these cases is that the court is also going out of its way not to intervene—even if that means editing or rewriting the lower court rulings along the way or ignoring tempting constitutional questions on the separation of powers. The justices might just be uninterested in the arguments presented to them. They might also remember keenly what happened almost two years ago just across the street from where they work.