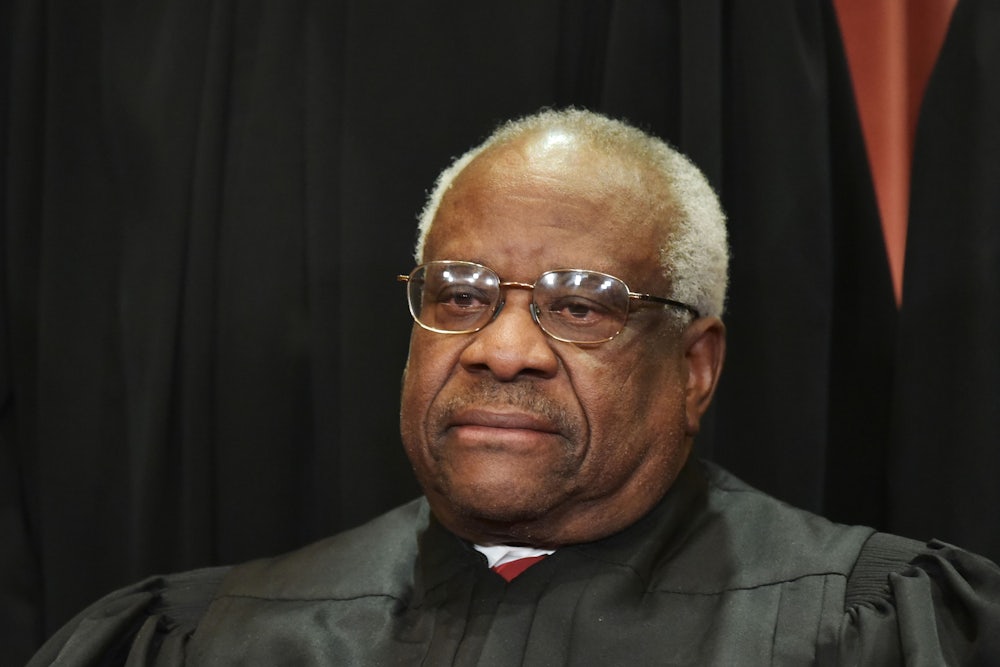

There’s an old adage that if you want a friend in Washington, buy a dog. Justice Clarence Thomas has proven it wrong. Thanks to investigations by ProPublica and other news organizations over the last month, we now know that the Supreme Court’s most senior justice has some really, really good friends in the halls of American power.

Harlan Crow, a GOP megadonor whom Thomas befriended after joining the court in the early 1990s, surely ranks at the top of the list. He went on luxury vacations around the world with the Thomases at his own expense for decades. He paid the $6,200 monthly tuition for Thomas’s grandnephew at a private boarding school. Crow even bought Thomas’s mother’s house in 2014 and let her continue to live there for free, saving her tens of thousands of dollars at minimum in rent and property taxes.

The Thomases’ lucrative friendships hardly end there. Another important pal is Leonard Leo, an executive vice president at the Federalist Society. Leo is one of the centers of gravity around which the rest of the conservative legal movement orbits. He played a key role in confirming almost every Republican-appointed justice since Thomas. The judicial power broker often spends his time with Crow and Thomas on various outings. Leo also paid Ginni Thomas, Clarence’s wife, roughly $100,000 for “consulting” for the Judicial Education Project whilst endeavoring to keep her name off of any related financial records.

Thomas’s allies and defenders, who are legion in conservative circles, have an impressive array of defenses for all of these transactions. National Review’s Rich Lowry mocked ethics concerns about the highly favorable rental arrangement for Thomas’s mother with the headline “BREAKING: Harlan Crow and Clarence Thomas Once Conspired to Aid a Penniless Widow.” Mark Paoletta, Thomas’s friend, biographer, and apparent spokesman, claimed that Thomas wasn’t required to disclose the tuition because Thomas’s grandnephew—whom he has raised as a son since the age of six—doesn’t legally count as a “dependent child” under the Ethics in Government Act.

The most interesting defense came from Leonard Leo, who spoke to The Washington Post about the payments he made to Ginni Thomas and the “Judicial Education Project.” He noted, correctly, that she had a long history in conservative activism that predated both her marriage to the justice and his confirmation to the Supreme Court. As for his instruction to keep her name out of financial records, Leo had an explanation for that too. “Knowing how disrespectful, malicious and gossipy people can be, I have always tried to protect the privacy of Justice Thomas and Ginni,” he claimed.

This privacy goal aligns well with one of Thomas’s own missions on the court. Throughout his tenure, he has consistently voted to make it easier for wealthy Americans to influence the political system. His opposition to any campaign-finance contribution limits is already well known. Less appreciated is Thomas’s consistent belief that disclosure requirements, especially in the political sphere, generally violate what he describes as a First Amendment right to anonymously participate in politics.

In the 2010 case Citizens United v. FEC, for example, Thomas signed on to most of Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion that struck down major provisions in the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. This was no surprise: He had previously voted against the law’s core provisions as a dissenter in McConnell v. FEC, one of the first cases to consider its constitutionality. In Citizens United, however, Thomas parted ways with even his fellow conservatives when it came to the law’s disclosure requirements for campaign contributions.

Kennedy wrote that keeping the disclosure requirements, which courts had previously upheld, was especially important as the court struck down other restrictions on corporate campaign spending. “With the advent of the Internet, prompt disclosure of expenditures can provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable for their positions and supporters,” he wrote. “Shareholders can determine whether their corporation’s political speech advances the corporation’s interest in making profits, and citizens can see whether elected officials are ‘in the pocket’ of so-called moneyed interests.”

Thomas strenuously disagreed with that portion of Kennedy’s ruling. As an example, he wrote at length about the hostile treatment that proponents of Proposition 8, a constitutional amendment in California that sought to ban same-sex marriages, had received for their views. In Thomas’s view, the First Amendment shielded them and others from facing pressure or criticism for anonymously participating in the public sphere. “These instances of retaliation sufficiently demonstrate why this court should invalidate mandatory disclosure and reporting requirements,” he argued in his partial dissent.

He also warned that disclosure requirements could allow the government to conduct pressure campaigns as well. His only evidence for this proposition came from anecdotal claims in a 2008 Wall Street Journal opinion column, where a columnist quoted a candidate for attorney general of West Virginia who blamed his fundraising woes on donors’ purported fear of retaliation from his opponent. From that column’s hazy insinuations, Thomas drew broader conclusions. “Disclaimer and disclosure requirements enable private citizens and elected officials to implement political strategies specifically calculated to curtail campaign-related activity and prevent the lawful, peaceful exercise of First Amendment rights,” he argued. (Emphasis his.)

That same term, the court also heard Doe v. Reed. The case involved a challenge to a Washington state public records law and the state’s referendum and initiative process. The process required a certain number of signatures to place a referendum or initiative on the ballot. Those signature petitions were subject to disclosure by the public records law, allowing Americans to look up who had signed them and verify that they were real. An anonymous signer sued to challenge the law, arguing that it violated their associative rights under the First Amendment.

In an 8–1 decision, the court rejected that claim and upheld the disclosure of referendum petitions. Thomas was the sole dissenting justice. Washington had argued that the disclosures were justified for election-integrity reasons, citing the risk of forged signatures. But Thomas argued that the First Amendment’s protection of anonymous political participation trumped even those concerns. “We should not abandon those principles merely because Washington and its amici can point to a mere eight instances of initiative-related fraud,” he argued.

Thomas concluded that this reasoning applied even when someone signed a public record with their own name. “The First Amendment rights at issue here are associational rights, and a long, unbroken line of this Court’s precedents holds that privacy of association is protected under the First Amendment,” he claimed. “The loss of associational privacy that comes with disclosing referendum petitions to the general public under the [Public Records Act] constitutes the same harm as to each signer of each referendum, regardless of the topic.”

More recently, in the 2021 case Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Becerra, the Supreme Court appeared to drift closer to Thomas’s position on disclosure requirements. Two conservative political organizations challenged a California law that required nonprofit groups to disclose their major donors to the state attorney general’s office to help police charity fraud. Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the court, ruled that this violated the First Amendment’s right to free association. “We are left to conclude that the [California] Attorney General’s disclosure requirement imposes a widespread burden on donors’ associational rights,” he wrote.

Thomas voted with the majority this time, but not without writing a separate opinion to distinguish himself from his colleagues on certain technical issues. He repeated his stance that disclosure laws in the political sphere should be viewed by courts under the strict scrutiny standard, which is the highest judicial threshold for the government to overcome. The majority had struck down the law under a slightly less intense standard. “Laws directly burdening the right to associate anonymously, including compelled disclosure laws, should be subject to the same scrutiny as laws directly burdening other First Amendment rights,” he wrote.

Virtually everyone agrees on some First Amendment protections for anonymity in the political sphere. One of Thomas’s first writings on the matter came, for example, in a case involving the right to anonymously publish political pamphlets. But Thomas has elevated that general principle into a core free-speech right and voted to strike down even transparency measures with broad political support to enact it.

If his vision of the First Amendment had prevailed for the last ten years, no one would know that Harlan Crow was a GOP megadonor unless he or the recipients of his largesse told someone. No one would know where and how Leonard Leo is soliciting billion-dollar donations to his small empire of conservative judicial “education” groups. And Americans might not know the full extent of Thomas’s financial entanglements—sorry, I meant his friendships—with them.