Last month, the conservative writer Ramesh Ponnuru published an op-ed in The Washington Post arguing that Democrats “have lost the debate about the role of courts in our democracy.” He detailed how conservatives over two generations “developed a comprehensive strategy, including politically powerful rhetoric,” to shift the federal courts toward their way of thinking. “Judges shouldn’t rewrite the law in the guise of interpreting it, they said; judges should be umpires, not players taking a turn at bat,” wrote Ponnuru, the editor of National Review. “Conservatives warned against letting judges have wide leeway to fill in the meaning of apparently vague language, instead urging them to be constrained by what the informed public understood the words of the law meant when it was ratified.” By which he means, of course, originalism.

Ponnuru is right. Conservatives have won this debate—or at least are winning it handily—because they recognized ages ago that they’re engaged in a political war, that the war is about the substantive meaning of the Constitution, and that politically effective rhetoric is critical to victory. The left, with a few notable exceptions I’ll highlight below, has not. That must change, quickly and drastically, if there’s to be any hope of preserving liberal governance from the Supreme Court supermajority we may have to live with for decades and from the broader threats to constitutional democracy we’re witnessing on a scale unequalled since the Civil War. And the left should wage this war on the conservatives’ own turf.

Ponnuru might be right about conservatives’ rhetorical success, but the tacit premise of his essay—that conservatives alone embrace originalism—is dead wrong. That could have been a fair point in the 1980s, when President Reagan’s second-term Attorney General Edwin Meese, Judge Robert Bork, Justice Antonin Scalia, and other luminaries of the new legal right first hoisted the banner of originalism—and liberal Justice William Brennan responded with a dubious counterpoint slogan, “living constitutionalism.” But not today. While some in the media and even in the Democratic Party conflate originalism with legal conservatism, a compelling contrary vision has emerged on the left: that rigorous fidelity to the text and history of the Constitution—a holistic interpretation that includes its amendments as well as legislative debates at the time, as opposed to conservatives’ penchant for cherry-picking isolated provisions out of context—often yields liberal results.

As Harvard Law’s Cass Sunstein wrote in this magazine nearly a quarter-century ago, while “Justice Scalia is the most famous originalist; in the law schools the most influential originalist may be Akhil Reed Amar, an ingenious and prolific scholar.” Unlike conservative originalists, he observed, Amar contends that “a fair reading of text and history supports liberal, sometimes even radical, conclusions.” Amar was soon joined by his Yale Law colleague Jack Balkin, who likewise stressed, “We follow the original meaning of words in order to preserve the Constitution’s legal meaning over time, as required by the rule of law.” But along with Amar, Balkin recognized that the Constitution’s terse terminology, many of its specific provisions, and key explanations by the Framers prescribed broad authority for future generations to adapt to changing circumstances and evolving political and moral precepts.

The vision elaborated by the two Yale professors and their followers is not simply a liberal spin on the right’s approach to originalism. If anything, it’s more punctilious in plumbing the original meaning of particular text and in contextually grounding interpretations in the overall—amended—document. Unlike the conservative originalists channeled by Ponnuru, they cast the Constitution, in Balkin’s terms, as a “framework … not to prevent future decisionmaking but to enable it.” As Amar asks, “How did later generations of constitutional Amenders reconfigure the system?” In other words, as with any legal document, amendments can change not only the thrust of the whole, but the meaning of pre-amendment provisions and decisions. For example, the Nineteenth Amendment, which barred denial or abridgment of the right to vote on the basis of sex, should render constitutionally suspect laws disadvantaging women enacted during the centuries when women were barred from choosing the legislators who adopted gender-discriminatory laws, as well as judicial decisions upholding them. More specifically, this means that the Nineteenth Amendment should have effectively stripped from constitutional law the misogynistic “traditions” relied upon by Justice Samuel Alito’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health opinion that overturned Roe.

Liberal originalists’ most important contribution is the insight they share with Ponnuru and his conservative allies: that constitutional interpretation is not just for judges and lawyers in lawsuits but rather forged in what Amar has called a “constitutional conversation” and others have labeled “popular constitutionalism.” Balkin starts a 1998 law review article, co-authored with University of Texas’s Sanford Levinson, with Frederick Douglass’s famous 1860 speech in Glasgow, Scotland, rebutting Dred Scott v. Sandford, the U.S. Supreme Court’s noxious ruling that the Constitution barred African American individuals from citizenship or “any rights that a white men is bound to respect.” In that speech, Douglass advanced what he called a “strict constructionist” argument that “only the text,” not the subjective expectations of drafters or ratifiers, or “commentaries” or judges “who wished to give the text a meaning apart from its plain reading, was adopted as the Constitution of the United States.” Nowhere in the document did the word “slavery” appear, Douglass noted, “nor any provisions preventing Congress or individual states from abolishing slavery.” Just as Douglass’s antislavery reading of the Constitution eventually became the law of the land, Balkin and Levinson stressed that transformational constitutional changes typically start with well-designed political and social movements that articulate new interpretations and move them from “off the wall” to “on the wall,” well before they are blessed by the Supreme Court.

Unlike Douglass, contemporary liberal leaders largely have not recognized that, in our democratic polity, battles over the meaning of the Constitution are inherently political, and must be waged as such. To correct that ahistorical misperception, liberals must shed a related habit: the visceral antagonism to the label “originalism.” Berkeley Law dean and star litigator Erwin Chemerinsky, with whom I rarely disagree and whom I hugely admire, published a book in 2022 whose title, Worse Than Nothing: The Dangerous Fallacy of Originalism, unwittingly reinforces Ponnuru’s false claim that liberals have “nothing”—no strategy, no theory to counter conservatives’ originalism. They do, as I’ve demonstrated above, but liberal leaders have largely failed to engage with conservatives’ originalist sloganeering.

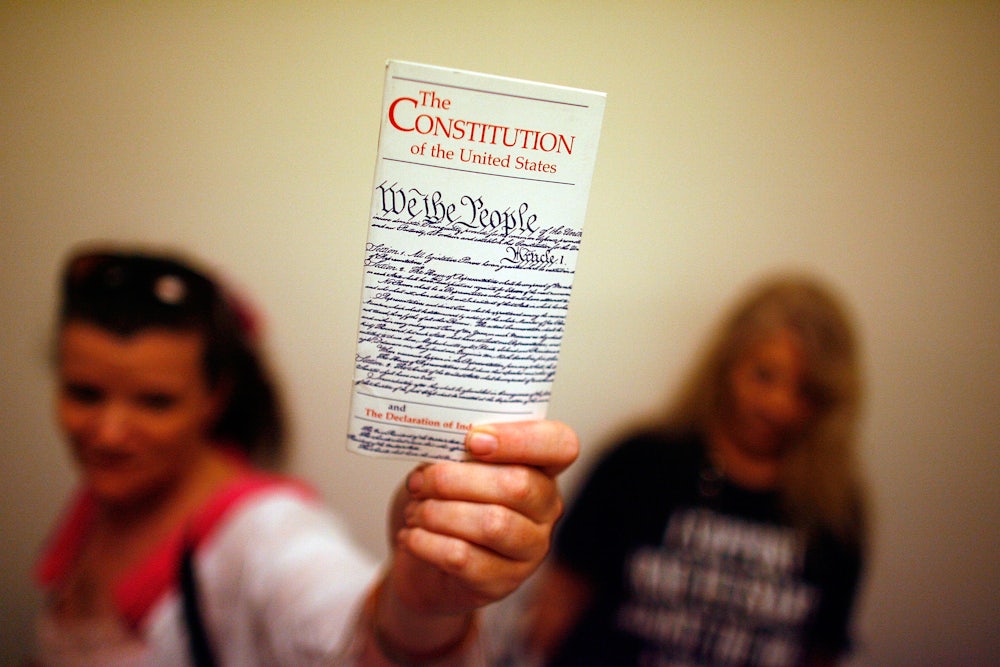

The label “originalism” itself does not, of course, galvanize broad swaths of everyday Americans; most do not know or care what it means, if they have heard it at all. But conservatives’ endless professions of fealty to originalism, together with liberals’ long-standing scorn or indifferent silence, has led to widespread credence that conservatives take seriously the actual words of the Constitution and what the Framers had in mind when they wrote or ratified them, and liberals … well, not so much. Given Americans’ veneration of the Constitution as secular scripture and their regard for the rule of law, such perceptions, left unanswered, damage liberal prospects in the wars over the Constitution and the courts.

Liberals also often fail to expose conservative stratagems that purport to be “originalist” but actually bypass the original meaning of that text. A good example appears in Ponnuru’s op-ed. He writes that broad language in the Constitution must be “constrained by what the informed public understood the law meant when it was ratified,” which is vague enough to allow for the actual enacted language to be subordinate to contemporaneous societal practice. But this brand of argument has long been discredited, by principled conservative originalists no less than liberals. Were it otherwise, Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed state-sponsored racial segregation in schools, could never have been decided; when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, racial segregation prevailed in schools at all levels across the nation, North as well as South.

Similar examples abound. In his Dobbs opinion, Justice Alito argued that when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted in 1868, a majority of states outlawed abortion; hence, its drafters and ratifiers could not have intended its broad phrases to sanction a right to abortion. In a co-authored dissent, the three liberal justices, Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor, countered that the “the Framers (both in 1788 and 1868) ... did not define rights by reference to the specific practices existing at the time.” After all, laws are routinely enacted to change existing practices, not freeze them.

The Dobbs dissent yields two points important for liberals. First, there is no inconsistency or conflict between embracing originalist messaging and highlighting the equally, often more important messaging Justice Breyer in particular famously favors, about real-world consequences at stake in politically significant legal battles. En route to spelling out the cataclysmic impact of freeing states to outlaw abortion, Breyer and his two colleagues recognized that it only strengthens their case to enlist the Constitution’s text and its Framers on their side: “In the words of the great Chief Justice John Marshall, our Constitution is ‘intended to endure for ages to come, and must adapt itself to a future seen dimly,’ if at all. That is indeed why our Constitution is written as it is.… And this Court … has kept true to the Framers’ principles by applying them in new ways, responsive to new societal understandings and conditions.” Second, liberals do not need to talk the talk by embracing the label of originalism. They just need to walk the walk, by similarly deploying canny text- and history-based arguments.

America’s long-held democratic principles are under threat by the far right, and yet too many liberals remain reluctant to rebrand and wrap themselves in the Constitution and its amendments. But it’s those texts themselves, and their historical context, that can save the very liberal governance that those documents prescribe—if only the left would learn to embrace and reframe them for the better of the nation. This is an existential struggle, and doing nothing is not an option.