Four years ago, amid his successful campaign to unseat President Donald Trump, Joe Biden made a promise: to “keep foreign money out of elections” by “prohibiting foreign governments’ use of lobbyists.” “There is no reason why a foreign government should be permitted to lobby Congress or the Executive Branch, let alone interfere in our elections,” he said on his campaign site. “If a foreign government wants to share its views with the United States or to influence its decision-making, it should do so through regular diplomatic channels. The Biden Administration will bar lobbying by foreign governments.”

But after winning the presidency, Biden did no such thing. In fact, he even reversed some of the unexpected progress Trump had made on the issue. So it’s no surprise that Biden didn’t mention banning foreign lobbying during his now-aborted reelection campaign this year. Among the 2024 presidential candidates, only Nikki Haley proposed such a ban—and she was an imperfect vessel for that message.

The open question, then, is where does Kamala Harris stand on the issue? Or, given that her nascent campaign has been light on policy specifics, where should she stand?

It’s a matter of critical importance to our democracy, and one where Harris could make an immediate impact. As Americans know all too well now, thanks to Trump, Washington is saturated by influence from countries that are either outright hostile toward America or at least don’t have our best interest at heart. Still, despite this attention, the foreign lobbyists swirling around Washington—specifically the P.R. outfits, law firms, and consultancies who sign up as mouthpieces and foot soldiers for foreign dictatorships—have hardly slunk back to the shadows. If anything, they’ve only continued swelling, now pulling in billions of dollars.

Enter Harris. If she takes the White House, she’ll have the opportunity to cut the industry down to size, using all of the tools of the presidency—as well as her own background—to her advantage. The only real choice she needs to make is whether to reform and expand our existing laws that aim to limit foreign influence in our politics, or to pick up the mantle that Biden unceremoniously dropped and ban such influence outright.

Foreign lobbyists are primarily regulated by the Foreign Agents Registration Act, which passed in 1938 after congressional investigators discovered that Ivy Lee, an American widely considered the father of the public relations industry, had secretly been advising the Nazi regime. As I detail in my new book Foreign Agents, the revelations about Lee shocked both legislators and Americans alike—and led directly to the passage FARA.

The law is a simple construct, requiring foreign lobbyists to register themselves, their work, and their payments on behalf of foreign patrons. Unfortunately, for decades after its implementation, FARA was effectively an afterthought, with hardly any investigation or enforcement. That disinterest allowed the industry to continue growing and eventually reach into the highest rungs of the American political establishment.

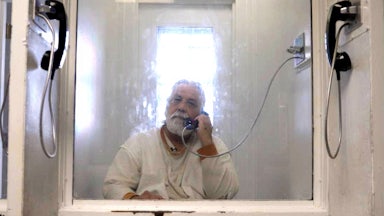

That all changed, however, with the rise of Trump—from Russia’s interference in the 2016 race to the recent revelations about foreign regimes bankrolling him as president. Since 2016, the U.S. has seen more high-profile prosecutions or guilty pleas of foreign lobbyists than ever before. While prosecutors haven’t had unblemished success—they bungled cases against figures like Trump adviser Tom Barrack, and even former Obama White House counsel Gregory Craig—the prosecutorial momentum picked up again over the past year with the conviction of Democratic Senator Bob Menendez for conspiring to act as a foreign agent of the Egyptian dictatorship, the first time in American history that a member of Congress had been convicted on foreign agent–related charges. Nor have prosecutors stopped there, as seen with recent charges against Democratic Representative Henry Cuellar and former National Security Council member Sue Mi Terry.

This is where Harris’s experience as a prosecutor would be unquestionably valuable. As president, she could push the Department of Justice to prioritize prosecutions—both the existing ones and new ones—of foreign lobbyists who are skirting American foreign lobbying requirements. She should also undo some of the Biden administration’s inexplicable failures in this area, specifically at think tanks and universities.

American think tanks have become some of the key vectors for foreign influence campaigns in recent years—largely because, unlike foreign lobbyists, they don’t have to register or disclose any of their work or payments from foreign benefactors, even when they receive millions from foreign dictatorships. Things began to change, perhaps surprisingly, under Trump, when Secretary of State Mike Pompeo began requesting that think tanks receiving such funding disclose these payments. And yet, for reasons that remain unclear, the Biden administration rolled back such requests. Rather than build out one of the few progressive, pro-transparency reforms of the entire Trump era, the Biden administration junked it wholesale—making think tanks a black box of foreign funding once more.

Or look at universities. While American universities have been required to disclose all significant payments from foreign regimes for decades, it wasn’t until the late 2010s that American regulators began investigating the matter—and promptly discovered that America’s leading universities had failed to disclose billions of dollars in foreign funding, from some of the most heinous regimes on the planet. In just one case study, investigators wrote that Cornell University failed to account for some $760 million in foreign funding—and “chose the word ‘dumbfounded’ to explain this reporting error and provided no explanation.”

Yet upon taking office, Biden scuttled all future investigations, even scrapping the online portal Americans could use to search through previous filings. As a result, disclosures have plummeted—making universities a black box again, too.

Both of these areas are relatively easy fixes for a President Harris—who, unlike Biden or Trump, doesn’t bring any baggage about suspicious foreign funding to the White House—and she should use her full powers as executive to do so. There is, however, one final area that Harris must build out with congressional allies: passing a range of proposed bills that would patch up America’s porous foreign lobbying regulations, and thwart many of the loopholes and openings foreign regimes still exploit to target Americans.

For instance, she should help push the passage of the bipartisan Stop Helping Adversaries Manipulate Everything Act, first introduced in 2022. Such legislation would outright bar Americans from lobbying on behalf of some of the planet’s most dictatorial regimes, including places like China, Russia, or Iran. It wouldn’t make the practice of foreign lobbying illegal, per se; given the constitutional protections for lobbying writ large, such an outright ban would be difficult to defend in court. But it would help stanch many of the networks still operating on behalf of these dictatorships—and present a model for future bills that could ban lobbying for similar regimes, even those who are close American partners.

There’s also the bipartisan Fighting Foreign Influence Act, which would target the kinds of nonprofits (think tanks, universities, etc.) that autocrats have increasingly turned to for access. Like other pro-transparency elements mentioned above, the bill wouldn’t bar American nonprofits from receiving funds from foreign regimes, but would instead require them to disclose the details of such financing—disclosures that the American populace could then sift through. For good measure, the bill also bars foreign lobbyists from donating to American political campaigns (thereby preventing these lobbyists from acting as effective cutouts for their dictator clients who want to fund American politicians).

These are just a sampling of the proposals floating around Washington, with groups like Transparency International’s U.S. chapter pushing many more versions of legislative fixes. But all of them would go a significant way toward beefing up America’s defenses against the foreign lobbying networks in Washington. Even then, Harris should be consulting legal scholars and other experts about further ways to hem in these networks, such as by preventing any members of her administration—or members of Congress and their staffers—from becoming foreign agents after leaving office. It’s likewise worth further studying the potential of banning the practice of foreign lobbying outright, even if that would be an uphill climb constitutionally.

Harris is, of course, no stranger to the threats of such foreign influence networks. Her opponent has been implicated in more shady foreign financing schemes than any other presidential candidate in American history, and Harris’s time on the Senate Intelligence Committee exposed her directly to the clear and present dangers of unchecked foreign influence campaigns. As president, Harris could finally do something about it, and rid Washington of this growing scourge.