President Donald Trump spent much of his first term in office trying to carry out orders and policies that were unlawful, unconstitutional, or both. Federal courts routinely ruled against him, and he characteristically responded by denouncing the judges and courts responsible.

The Supreme Court did not uphold every lower court decision, but it sided with them on an institutional level against the executive branch’s attacks. “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges,” Chief Justice John Roberts said in a rare public statement in 2018. “What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

Trump’s second term could hardly be more different—at least in terms of how the courts respond. The White House and the high court’s conservative majority now generally agree that Trump should be able to freely remake the federal government and the United States itself in his own authoritarian image. In doing so, some of the conservative justices have openly rebuked their fellow judges for obstructing him and defying the court.

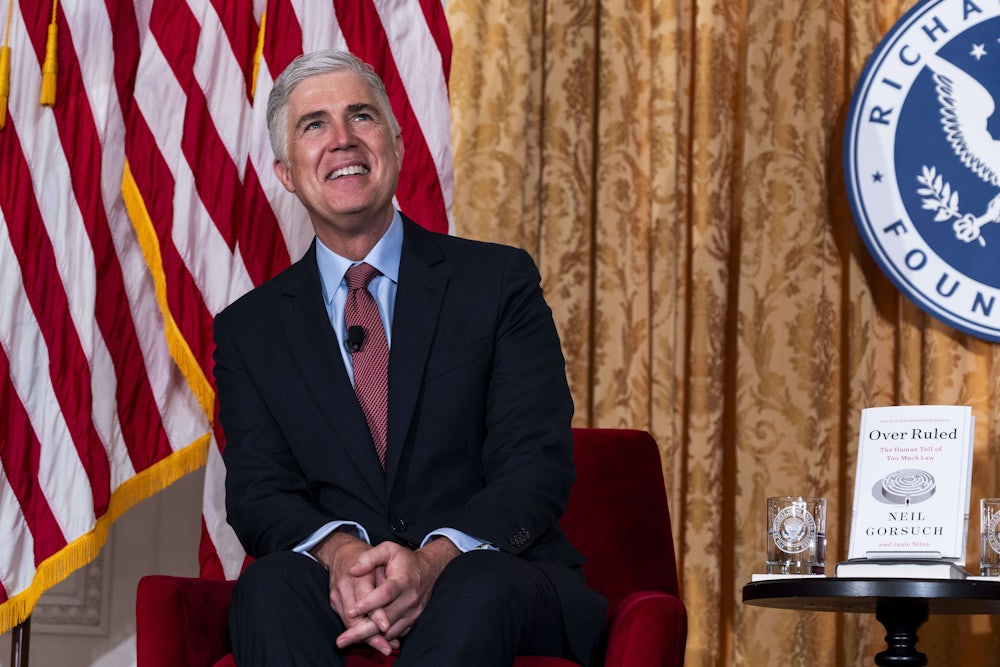

“Lower court judges may sometimes disagree with this court’s decisions, but they are never free to defy them,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in a separate opinion that Justice Brett Kavanaugh joined in full in a decision last month on funding freezes at the National Institutes of Health. The two justices effectively accused a lower court colleague of willfully disregarding the court’s precedents, an extremely serious charge to level against one of their ostensible colleagues.

Discontent is simmering in the lower courts, as well. NBC News’s Lawrence Hurley interviewed a dozen federal judges who complained on background about the Supreme Court’s approach to its shadow-docket cases, as well as the difficult positions into which the high court forces the lower courts in some notably high-stakes, high-profile cases. “It is inexcusable,” one unnamed judge told Hurley. “They don’t have our backs.” The same judge, citing the rise in violent threats, said that “somebody is going to die” if trends continue at their current pace.

Gorsuch’s rebuke came alongside a convoluted order in a Supreme Court case involving NIH grants. The Trump administration had frozen the already approved research grants shortly after taking office. Various recipients, including the American Public Health Association and other medical associations, sued to force the executive branch to disburse the funds to researchers, citing statutory arguments as well as the irreparable harm that their ongoing studies and projects would face.

A federal district court judge in Massachusetts vacated the NIH’s decision to terminate the grants. The First Circuit Court of Appeals declined to stay the lower court’s ruling, prompting the Trump administration to ask the Supreme Court to intervene. Solicitor General D. John Sauer claimed that the court in Massachusetts, as well as others around the country, were in open “defiance” of the Supreme Court’s rulings.

Sauer pointed to the court’s decision in April in Department of Education v. California, where the justices allowed the Trump administration to cancel billions in education-related grants to schools and universities around the country. A coalition of states had sued the federal government in response. A different federal district court judge in Massachusetts concluded that canceling the grants likely violated federal law. Accordingly, he issued a temporary restraining order, or TRO, that required the administration to keep making grant payments.

The Supreme Court stayed the district court’s TRO. In its brief, unsigned order, five of the conservative justices disagreed with the lower court judge’s interpretation of federal law, argued that the states should have instead filed their complaint in the Court of Federal Claims, and claimed that the factors that courts usually use when deciding whether to grant a stay went in the Trump administration’s favor.

Chief Justice John Roberts and the court’s three liberal justices signaled that they would have sided with the lower court. Justice Elena Kagan described the majority’s decision as a “mistake” in her dissent. “Nowhere in its papers does the government defend the legality of canceling the education grants at issue here,” she noted, then added that the court’s reasoning on the cancellation’s lawfulness was “at the least under-developed, and very possibly wrong.”

She also admonished her colleagues for their sloppiness in shadow-docket cases. “The risk of error increases when this Court decides cases—as here—with barebones briefing, no argument, and scarce time for reflection,” Kagan wrote. “Sometimes, the Court must act in that way despite the risk. And there will of course be good-faith disagreements about when that is called for. But in my view, nothing about this case demanded our immediate intervention.”

It is worth emphasizing here that the shadow docket—or, as the court sometimes describes it, the “emergency docket”—wasn’t always like this. The Supreme Court typically let lower courts manage ongoing litigation through stays and orders except in exceedingly rare instances. It wasn’t until 2016, when the court’s conservative justices intervened to block the Obama administration from issuing carbon-emissions rules for power plants, that the shadow docket suddenly became a major forum for American governance.

Since then, litigants have challenged nearly every major domestic policy initiative by the executive branch in federal court, leading to a flurry of motions and orders on whether to let the policy go into effect. The Supreme Court became the final arbiter in these disputes, either by letting the policy go into effect or by blocking it indefinitely until the high court could issue a ruling on the merits after extensive litigation. The justices didn’t rule on the EPA power-plant emissions case until 2022—six years and two presidents later. (I’ll give you three guesses on whether they upheld it.)

When the Supreme Court decides cases on its normal “merits” docket, it does so after extensive briefing from both sides and from third parties. The court holds oral arguments to fully discuss and refine the various points of law and their broader implications. Then it releases lengthy decisions that explain its reasoning and how it reached its conclusions. On the emergency docket, however, the justices effectively fly by the seat of their robes and often provide no written explanation of their decisions. (More on that later.) That opacity led legal scholars to describe it as the “shadow docket,” and the name stuck.

That brings us back to the NIH case and the district court’s alleged “defiance” of the high court. Once again, the Justice Department asked the justices to intervene, claiming in hyperbolic terms that “district-court defiance of this Court’s decision in California has grown to epidemic proportions” and that “this sequel poses an even bigger affront to bedrock legal principles than the original.” These claims might be more credible if the Trump administration had not itself defied court orders a few months ago in some of the deportation-related cases.

The court’s eventual ruling in the NIH case is arcane and convoluted, with neither side getting everything they wanted. Suffice it to say that the conservative majority reversed enough of the lower court’s order to allow Gorsuch to write a partial concurring/dissenting opinion chiding it for disobedience. He also claimed to spot a broader trend.

“If the district court’s failure to abide by California were a one-off, perhaps it would not be worth writing to address it,” Gorsuch wrote. “But two months ago another district court tried to compel compliance with a different order that this Court had stayed.” That was a reference to Department of Homeland Security v. D.V.D., where the justices allowed the Trump administration to deport noncitizens to random countries despite federal law prohibiting it.

“Still another district court recently diverged from one of this Court’s decisions even though the case at hand did not differ ‘in any pertinent respect’ from the one this Court had decided,” Gorsuch continued. That was a reference to Trump v. Wilcox, where the conservative justices allowed Trump to fire a member of the National Labor Relations Board even though federal law and 90 years of Supreme Court precedent said he couldn’t, and a similar later case where Trump fired the Democratic members of the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

“So this is now the third time in a matter of weeks this court has had to intercede in a case ‘squarely controlled’ by one of its precedents,” Gorsuch claimed, quoting from Supreme Court precedents. “All these interventions should have been unnecessary, but together they underscore a basic tenet of our judicial system: Whatever their own views, judges are duty-bound to respect ‘the hierarchy of the federal court system created by the Constitution and Congress.’”

Gorsuch’s pointed opinion has already drawn rare pushback from the lower courts. Judge Allison Burroughs, a federal district court judge in Massachusetts, issued an 87-page ruling earlier this week where she found that the Trump administration had illegally canceled billions in federal funding for Harvard University. The president has singled out Harvard and other prominent universities for ideological retribution over the past nine months as part of a broader authoritarian campaign against traditionally liberal institutions.

Her ruling against the funding freeze will likely come under Supreme Court scrutiny in the near future, and she anticipated that Gorsuch and some of the court’s other conservative justices might disagree with her interpretation of the relevant law and precedents. To that end, Burroughs explained that her ruling did not intend to defy the high court’s own judgment.

“The Court is mindful of Justice Gorsuch’s comments in his opinion in APHA and fully agrees that this Court is not free to ‘defy’ Supreme Court decisions and is, in fact, ‘duty-bound to respect “the hierarchy of the federal court system,”’” Burroughs wrote, citing Gorsuch’s opinion initially and then Supreme Court precedent later. “Consistent with these obligations, this Court (and likely all district courts) endeavors to follow the Supreme Court’s rulings, ‘no matter how misguided [it] may think [them] to be.’”

“That said,” she continued, “the Supreme Court’s recent emergency docket rulings regarding grant terminations have not been models of clarity, and have left many issues unresolved.” In the Department of Education case, she pointed out that the court’s “four-paragraph [unsigned] decision” did not explain how that case was “distinguishable” from a previous Supreme Court ruling that leaned in the schools’ favor “or other related, longstanding precedents.”

The NIH decision also had problems. Roberts and the court’s three liberals sided with the grant recipients. Four of the conservative justices sided with the Trump administration. Justice Amy Coney Barrett split the difference. Burroughs noted that didn’t amount to particularly helpful guidance for lower courts. “The outcome, which no party had requested, was, thus, inconsistent with the views of eight justices and, again, provided little explanation as to how [a relevant Supreme Court precedent], which the controlling concurrence again cited as good law, applied or was distinguishable,” she explained.

Burroughs acknowledged that the court was resolving these cases on an accelerated schedule without proper briefing or argument. “Given this, however, the Court respectfully submits that it is unhelpful and unnecessary to criticize district courts for ‘defy[ing]’ the Supreme Court,” she continued, “when they are working to find the right answer in a rapidly evolving doctrinal landscape where they must grapple with both existing precedent and interim guidance from the Supreme Court that appears to set that precedent aside without much explanation or consensus.”

This is a reasoned and judicious way to disagree with Gorsuch. Burroughs could have been less diplomatic by noting, for example, that the Supreme Court’s general approach to the shadow docket flipped like a light switch once Trump took office. While the court routinely blocked Biden administration policies from taking effect, even in cases where it ultimately sided with Biden on the merits, the justices now let Trump do virtually whatever he wants while litigation unfolds.

The Supreme Court even eliminated lower courts’ power to issue nationwide injunctions, in Trump v. CASA, after frequently allowing courts to use them against both Biden and first-term Trump policies. It also rewrote the balancing-of-equities calculus for cases involving the executive branch by holding that the government is “irreparably harmed” whenever it can’t enact its preferred policies. The policy in question was an executive order claiming to deny citizenship to children born on U.S. soil to noncitizen parents, in direct defiance of the citizenship clause’s text and history.

One could also quibble with Gorsuch’s description of the federal judiciary itself. The federal courts are stratified, but they are not hierarchical. Federal judges do not work for each other (or for anyone else, save for the American people in an abstract sense), and they certainly do not work for the Supreme Court. They are each independently appointed by presidents and confirmed by the Senate. Constitutionally speaking, there is no difference between Neil Gorsuch and a federal district court judge in Massachusetts, except for the jurisdictions of the courts on which they serve.

If Gorsuch is unhappy that lower court judges are struggling to apply the Supreme Court’s orders, it might be worth considering whether the high court itself is to blame. Lower courts appear to be more respectful of precedent than the Supreme Court itself. In the dismissal cases, for example, district courts have to choose between actual precedent like Humphrey’s Executor v. United States on whether the president can ignore for-cause removal protections or inferring the conservative majority’s preferred outcome from their assumed ideological views. Small wonder that they keep choosing the former over the latter.

Indeed, one problem is that the conservative justices also appear to have internalized the court’s ideological divide—that is to say, they appear to recognize that there is a distinctly conservative majority on the Supreme Court, that it won’t be going anywhere anytime soon, that its members share distinct goals for reshaping American law and precedent in their own image, and, most importantly, that the lower courts should act and anticipate accordingly.

The district court’s ruling in the NIH case, for example, does not really amount to “defiance” of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Department of Education case. As Roberts noted in his concurring opinion in the former, the lower courts in each case delivered substantially different rulings that raised different questions of law compared to the latter case. The lower court could therefore plausibly distinguish it from the earlier ruling.

These rulings do amount to defiance, however, if the court’s real shadow-docket decisions are “Trump can cut off federal funds and grants to whomever he wants” and “Trump can fire any federal official for any reason, except for Jerome Powell.” Those may be the rulings that the conservative majority wanted to hand down. Since they didn’t actually write them as such, the justices should not be surprised when lower courts don’t follow them as such or when they don’t leap to embrace maximalist views of executive power on their own. Even the most ardent supporter of judicial power does not think telepathy is among them.

The rebuke still prompted Judge William Young, who presided over the NIH case, to make a public apology to the justices “if they think that anything this court has done has been done in defiance of a precedential action of the Supreme Court of the United States,” during a court session earlier this week. Young, who became a federal judge the same year that Gorsuch graduated high school, explained that he “can do nothing more than to say as honestly as I can: I certainly did not so intend, and that is foreign in every respect to the nature of how I have conducted myself as a judicial officer.” Nothing in his storied career suggests otherwise.

Kavanaugh, for his part, also offered some recent public contrition. “It’s possible we screwed up, very possible, we’re human,” he reportedly told a judicial conference this week. “But it’s also possible, and oftentimes is the case, that it’s the product of nine of us, or at least five of us, trying to reach a consensus or a compromise on a particular issue that might be difficult. I’m fully aware that can lead to a lack of clarity in the law and can lead to some confusion, at times.”

Those are fair points. They also strongly counsel against the justices’ current approach to the shadow docket in general. The Supreme Court is not obligated to treat every motion for a stay from the Trump administration as an emergency worthy of its immediate intervention, nor does it have to use those motions as a vehicle to create significant and unsettling shifts in long-standing precedent. The justices are more than able to rewrite precedent on the merits docket. As long as the court continues to wreak jurisprudential havoc with its emergency rulings, it should not be surprised if lower courts struggle to consistently interpret them. Like more than a few other woes in modern American life, this is all a monster of the Supreme Court’s own creation.