The Supreme Court has done great damage to the nation’s constitutional order in recent years. So it is almost a relief to be able to write about something that the justices—or at least some of them—are doing to repair it.

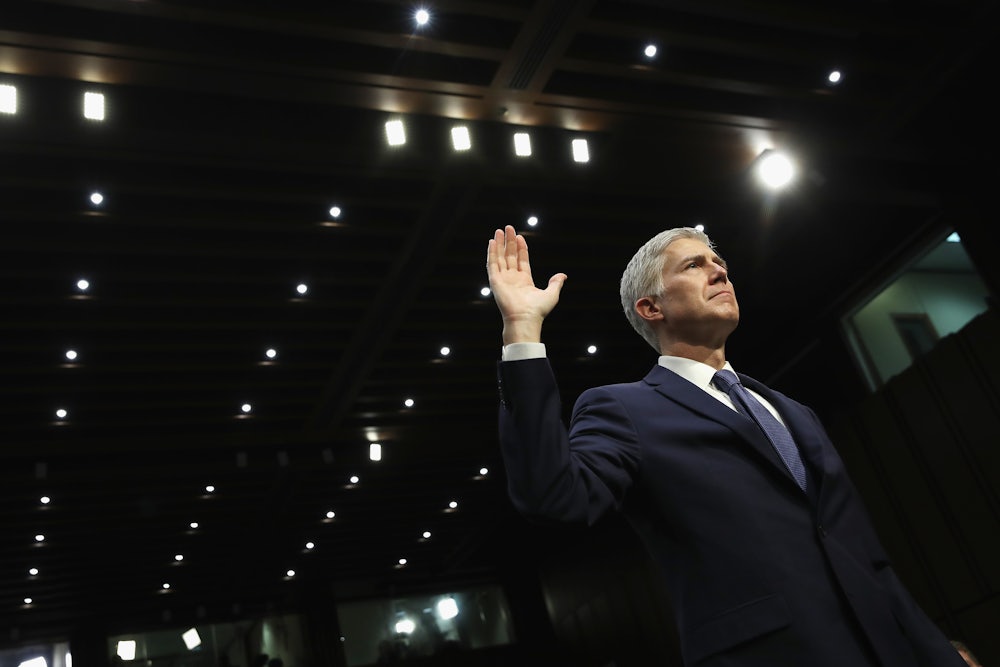

Justice Neil Gorsuch has carved out a niche for himself as one of the court’s most thoughtful justices on Indian law and tribal sovereignty over the past eight years. In recent years, he has argued for restoring what he describes as the proper place for tribal nations in the American constitutional firmament—a place where tribes would enjoy far greater sovereignty and self-government than they currently hold.

Earlier this week, the court declined to hear Veneno v. United States, a case involving a Jicarilla Apache man who was charged with domestic assault against another tribal member on tribal land. The defendant raised various challenges to his conviction, including some procedural challenges and a Sixth Amendment claim for closing the courtroom to the public at one point during jury selection.

The real import of his case is its challenge to United States v. Kagama, a nineteenth-century Supreme Court case that laid the foundation for near-total federal power over the internal affairs of tribal nations. Gorsuch, in a dissent from the court’s refusal to hear the case, welcomed the challenge and urged his colleagues to overturn the precedent.

“Kagama helped usher into our case law the theory that the federal government enjoys ‘plenary power’ over the internal affairs of Native American tribes,” Gorsuch wrote. “It is a theory that should make this Court blush. Not only does that notion lack any foundation in the Constitution; its roots lie instead only in archaic prejudices. This Court is responsible for Kagama, and this Court holds the power to correct it. We should not shirk from the task.”

It is not yet clear how many of Gorsuch’s colleagues are in favor of his proposed constitutional revolution for tribal sovereignty. Only one of them, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined his dissent. Gorsuch’s call in this case and others to revisit the basics of modern Indian law is a welcome and long-overdue one.

It is hard to properly summarize centuries of Indian law or the history of Native American relations with the federal government. As a starting point, the Constitution recognizes the existence of sovereign Native American nations within America’s borders. Article 1 allows Congress to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.” In the Indian-law context, this is known as the Indian commerce clause.

In the 1883 case Ex parte Crow Dog, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned the federal conviction of a Lakota Sioux man who had murdered a Lakota chief on tribal land within the Dakota Territory. The tribal council compelled Crow Dog, the murderer, to make restitution to the slain man’s family and settled the matter internally. Federal prosecutors then opted to try him for murder under territorial law.

When Crow Dog’s case reached the high court, the justices reaffirmed tribal sovereignty by concluding that federal courts did not have jurisdiction over a purely internal matter for the Lakota. (Crimes involving nonmembers on tribal land or occurring between tribal members on nontribal land could and can still be prosecuted.) In response, Congress enacted the Major Crimes Act of 1885, or MCA, which explicitly extended federal criminal jurisdiction to tribal lands for “major” crimes like murder, manslaughter, rape, and other felonies.

Three months after the MCA’s enactment, a Yurok man named Kagama killed another man over a property dispute on tribal land in northern California. Federal prosecutors indicted him for murder under the new law. In response, Kagama’s lawyers challenged the MCA’s constitutionality. They argued that Congress had no jurisdiction over crimes between tribal members on tribal land. The Indian commerce clause, they explained, could not be read to allow prosecutions for crimes that are not ordinarily prosecuted by the federal government.

The court’s opinion in United States v. Kagama was also unanimous. This time, however, it dealt a severe blow to tribal sovereignty. Justice Samuel Miller, who wrote for the court, channeled the biases of his era by describing tribal nations as existing in a state of “pupilage” under American civilization, reducing them in the eyes of the law from largely autonomous nations to colonial subalterns.

“These Indian tribes are the wards of the nation,” he wrote. They are communities dependent on the United States—dependent largely for their daily food; dependent for their political rights. They owe no allegiance to the states, and receive from them no protection. Because of the local ill feeling, the people of the states where they are found are often their deadliest enemies. From their very weakness and helplessness, so largely due to the course of dealing of the federal government with them, and the treaties in which it has been promised, there arises the duty of protection, and with it the power.”

Kagama is a low point in the Supreme Court’s history of constitutional interpretation—to describe its reasoning is to expose the lack of it. Miller disclaimed the idea that Congress could enact the MCA via the Indian commerce clause, then claimed the federal government could enact the law because it needed to enact it. The court’s casual bigotry only underscored its flaws.

“The power of the General Government over these remnants of a race once powerful, now weak and diminished in numbers, is necessary to their protection, as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell,” Miller wrote. “It must exist in that Government, because it never has existed anywhere else; because the theater of its exercise is within the geographical limits of the United States; because it has never been denied; and because it alone can enforce its laws on all the tribes.”

The “power” described in Kagama came to be known as the plenary-power doctrine in later cases. Much of Congress’s power over tribal nations and their internal affairs comes from this doctrine, and it remains a vital force in Indian law to this day. But as Miller’s own opinion demonstrated, the doctrine’s basis was unmoored from anything in the constitutional text but opportunity and convenience.

Gorsuch’s project—though I doubt he would describe it as such—is to restore the original balance of power between tribal nations and the rest of the American constitutional system. In the founding era, the justice has explained, the federal government’s relations with Native American nations was largely conducted through treaties and diplomatic negotiations, as with any other sovereign. The Constitution’s structure reflects that perspective to this day.

Westward expansion shifted that relationship toward one of pure conquest, subjugation, and assimilation. By the time the court decided Kagama, the court erroneously read that mindset into the law. The plenary-power approach, Gorsuch noted, “lacked any basis in the Constitution” and “injected a new incoherence into our Indian-law jurisprudence.”

“Since the founding and to this day, this Court has acknowledged that Congress enjoys only limited and enumerated powers and that Tribes are ‘sovereign and independent states,’” Gorsuch wrote in his Veneno dissent, quoting from precedent. “Yet, thanks to decisions like Kagama, this Court has also sometimes suggested that Congress enjoys plenary power to ‘regulate virtually every aspect of the tribes.’ Those two propositions of course clash because only one is true.”

Gorsuch’s interest in Indian law has drawn media and scholarly attention over the years, especially after the ruling in the 2020 case McGirt v. Oklahoma. I have written about the matter myself from time to time. Though I would not presume to read his mind, it seems apparent to me from his writings that Gorsuch simply treats Native American tribal nations as legitimate constitutional actors. His views only seem radical because his colleagues, past and present, have given such short shrift to tribal sovereignty. To that end, he has sharply questioned other precedents that shape Indian law like the “discovery doctrine,” which nineteenth-century Americans invoked as a legal basis to strip Native American nations of their lands.

“If ‘discovering’ a land is enough to secure certain rights over it, one might wonder why Native Americans hadn’t obtained those rights over their lands long before Europeans arrived,” Gorsuch observed in a footnote. “As one commentator had already asked by the time of the Nation’s founding: ‘If sailing along a coast can give a right to a country, then might the people of Japan become, as soon as they please, the proprietors of Britain’?”

There is a certain amount of revisionism at work here, of course. Early Americans often warred with neighboring tribal nations, and the Founders often hoped to either “civilize” or remove Native Americans from lands that they hoped to acquire and settle. Since the constitutional text itself does not mention this context, however, Gorsuch is able to dismiss the Kagama court’s bigotry as “archaic colonial prejudices nowhere found in our republican Constitution and wholly antithetical to it.”

Gorsuch’s anti-colonialism isn’t restricted to Indian law. In the 2022 case United States v. Vaello Madero, he also called for the court to revisit and overturn the Insular Cases, a series of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century rulings that set forth the lesser constitutional status of Puerto Rico and other “unincorporated” U.S. territories. Those rulings allow the federal government to treat the territories as colonial possessions.

“The flaws in the Insular Cases are as fundamental as they are shameful,” he continued. “Nothing in the Constitution speaks of ‘incorporated’ and ‘unincorporated’ Territories. Nothing in it extends to the latter only certain supposedly ‘fundamental’ constitutional guarantees. Nothing in it authorizes judges to engage in the sordid business of segregating territories and the people who live in them on the basis of race, ethnicity, or religion.”

If the court were to adopt Gorsuch’s interpretation of Indian law, he argued that it would not lead to disaster. Tribal governments would be free to punish “major” crimes according to their own laws and customs. “Equally, if tribes and the [federal] government decide that a degree of federal involvement in tribal justice is mutually beneficial, the Constitution affords a lawful way to achieve that end: by treaty,” he explained.

It is doubtful that the rest of the court will adopt this interpretation anytime soon. There are signs that the other justices are unwilling to change course on tribal sovereignty. Gorsuch joined with the court’s four liberal justices in McGirt to recognize that roughly half of the state was still Indian country. Two years later, five conservative justices partially nullified that ruling’s outcome by allowing states to prosecute some crimes on tribal land, prompting a furious dissent from Gorsuch.

More recently, in Haaland v. Brackeen, the court decided against upholding a Fifth Circuit ruling that would have partially dismantled the Indian Child Welfare Act. Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion where he laid out his holistic understanding of the Constitution and tribal sovereignty. But he ultimately spoke alone: No other justice joined that opinion, and the rallying of votes behind Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s cautious majority decision felt like a gentle repudiation of his more revolutionary approach.

This is not to say that Gorsuch’s work on tribal sovereignty does not matter, of course. For now, it will speak to future lawyers and justices who may see the wisdom of his interpretation with the benefit of time. “Our plenary power decisions demand reconsideration if this court is ever to bring coherence to the law and make good on its promise of fidelity to the Constitution,” he wrote on Monday. “A matter so grave ‘cannot be settled until settled right.’”

That closing quote came from Justice John Marshall Harlan, whose dissent from Plessy v. Ferguson and the “separate but equal” doctrine would be vindicated 58 years later in Brown v. Board of Education’s ruling against racial segregation. Whether it will take six decades or longer to repair Indian law is now up to Gorsuch’s colleagues.