The Supreme Court has laid waste to most of the nation’s efforts toward campaign finance reform and money-in-politics regulation over the past 15 years. Later this fall, it will have the opportunity to expand opportunities for corruption in the American political system even further.

In National Republican Senatorial Committee v. Federal Election Commission, the justices will consider whether Congress’s ban on “coordinated party expenditures”—that is, election spending by political parties that is coordinated with a federal candidate—violates the First Amendment. A victory for the NRSC would allow wealthy Americans to exceed donation limits by funneling the money through a political party instead, blowing yet another hole in federal campaign finance restrictions.

Federal campaign finance law sets limits on how much money an individual can donate to a candidate’s campaign for federal office. Congress imposed those limits to prevent the appearance or reality of quid pro quo corruption in the nation’s democratic structures. To that end, federal law also generally prohibits political parties from coordinating their campaign advertising expenditures with candidates and campaigns. This is designed to ensure that candidates and donors can’t evade contribution limits by giving the money to a third party that will do the same work on a candidate’s behalf.

In the 2001 case Federal Election Commission v. Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Committee, the FEC brought an enforcement action against a Republican Party group that ran attack ads against a Democratic congressional candidate in Colorado. (The courts refer to this case as Colorado II because it was the Supreme Court’s second ruling in the lawsuit. For clarity and brevity, I will do the same.) The GOP group argued that the enforcement action violated its First Amendment rights to free speech. The Supreme Court disagreed, applying the framework it had first developed in Buckley v. Valeo in 1976.

“There is no significant functional difference between a party’s coordinated expenditure and a direct party contribution to the candidate, and there is good reason to expect that a party’s right of unlimited coordinated spending would attract increased contributions to parties to finance exactly that kind of spending,” Justice David Souter wrote for the 5–4 majority. “Coordinated expenditures of money donated to a party are tailor-made to undermine contribution limits.”

Since Colorado II, the Supreme Court has significantly loosened restrictions on money in politics. The court’s conservative majority struck down limits on independent expenditures by corporations and unions during an election campaign in the landmark 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. FEC. That ruling helped fuel the rise of super PACs, which can make unlimited expenditures so long as they do not coordinate with candidates in their decisions. (For a host of reasons, the restrictions on coordination are but a legal fig leaf.) Four years later, in the 2014 case McCutcheon v. FEC, the conservatives also struck down aggregate contribution limits for wealthy donors.

Now the Republicans say it is time for the coordination limits with parties to fall. The GOP’s congressional fundraising arms, the National Republican Senatorial Committee and the National Republican Congressional Committee, sued the FEC along with then-Representative Steve Chabot and then-Senator JD Vance to overturn the limits on coordinated party expenditures. The lower courts, including the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, sided with the FEC because they said they were bound by Colorado II.

In its brief for the justices, the NRSC argued that the court’s 2001 opinion did not apply to this case because of substantial changes to the law since then. “While Colorado II rejected a facial challenge to an earlier version of the limits, Congress amended that law in 2014 to allow unlimited coordinated spending in certain areas, such as a candidate’s legal fees,” it correctly claimed. As a result, it argued that the justices could side with them without unsettling precedent.

But what’s the fun in that? The NRSC seemed to agree because it also really, really wants the court to overturn Colorado II. “That 5-4 aberration was egregiously wrong the day it was decided, and developments both in the law and on the ground in the 24 years since have only further eroded its foundations,” it said in its brief for the justices. “And far from some historical curio safely tucked away in a dusty volume of the U.S. Reports, the decision ‘lies about like a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority’ that seeks to limit political speech in the future.”

That last quotation comes from Justice Robert Jackson’s famous dissent in Korematsu v. United States, where he rejected the court’s decision to uphold Japanese American internment during World War II. It takes a certain kind of legal mind to implicitly equate party-candidate coordination limits to indefinite wartime detention in internment camps solely on the basis of race, but the National Republican Senatorial Committee was apparently up to the challenge.

The Federal Election Commission lacked a quorum during the lawsuit so it was unable to defend itself in court. That responsibility instead fell to the Justice Department. Earlier this year, Trump appointees at the department notified the justices that they agreed with the NRSC on the merits—shocker!—and would no longer defend the FEC. Both the NRSC and the Trump administration argued that the court’s moves had rendered Colorado II unnecessary.

The NRSC argued, for example, that Colorado II had “distorted both the law and the political process” by “emboldening speech regulators” and pushing donors toward super PACs. “The result is a more polarized process in which the mediating institution of political parties has been supplanted by less-restricted and less-accountable speakers,” they suggested. The Justice Department, on the other hand, described super PACs as “robust alternative avenues for political expression” whose existence watered down the original ban.

Since the actual parties mostly agreed with one another, the justices appointed a lawyer to argue the other position and allowed the Democratic National Committee to intervene in the case, as well. “[The NRSC] want this Court to facially invalidate a federal statute, overrule a long-settled precedent, and blow a hole in the campaign finance framework that Congress enacted to protect our political system from corruption,” the lawyer, Roman Martinez, told the justices in his brief. “The Court should decline the invitation.”

The DNC also insisted that Colorado II was good settled law. To that end, it also claimed that the justices could not overturn the 2001 decision without undermining other bedrock doctrines in how the First Amendment shapes federal campaign finance law.

“Colorado II follows directly from two settled principles of campaign finance law: Congress may regulate campaign contributions, and coordinated expenditures are the functional equivalent of contributions and may be regulated as contributions,” the group argued in its brief. “Colorado II correctly held that those principles apply to political parties just as they apply to any other group, and that the federal limits on coordinated expenditures by parties are ‘closely drawn to match a sufficiently important interest.’”

The Supreme Court has not taken up every invitation to overturn or reshape campaign finance law. Once the court’s conservative majority has taken up a case, however, it has invariably ruled in favor of the side that wants to weaken anti-corruption reforms. The most recent case came three years ago in FEC v. Ted Cruz for Senate, where the court’s conservatives voted in a 6–3 decision to allow wealthy candidates to loan unlimited amounts of money to their campaigns.

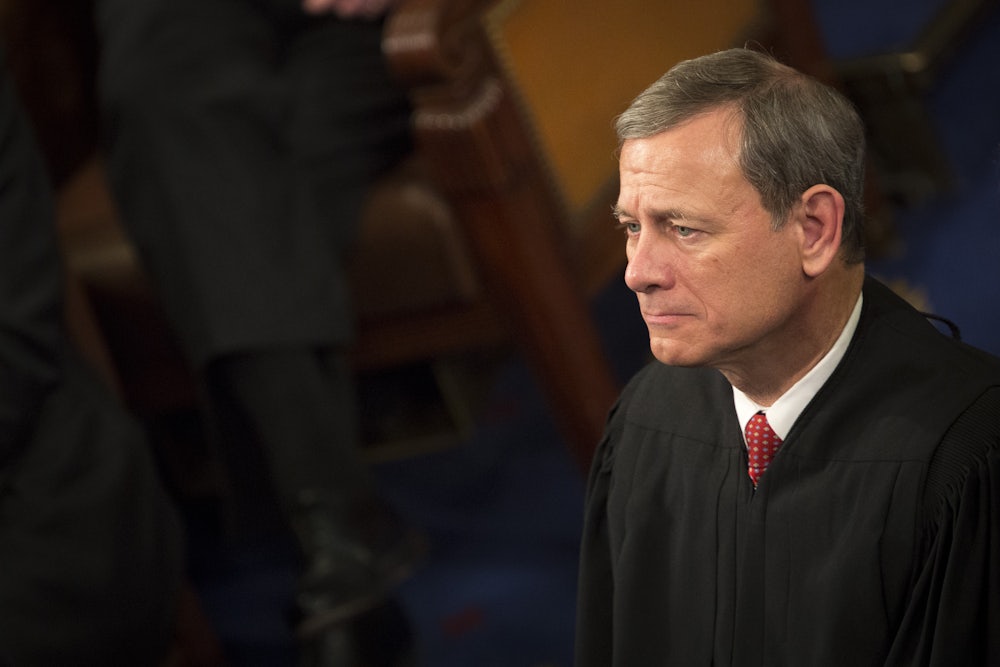

Indeed, pro-corruption rulings are one of the hallmarks of the Roberts court. Since its 2016 ruling in McDonnell v. United States, which narrowed the federal bribery statute, the conservative majority has consistently ruled in favor of public corruption defendants. Last year, the court went even further by creating “presidential immunity” out of thin air to allow presidents to commit crimes when they exercise their official powers, even in exchange for bribes and kickbacks.

One cannot really expect the Supreme Court’s conservative majority to reverse course on an ideological project to which they seem so fervently committed. At the same time, NRSC v. FEC would be a good opportunity for the justices to demonstrate that there are some outer bounds to the amount of corruption that they are willing to tolerate in America’s political system. Oral arguments will likely be scheduled for December or early spring.